Toxteth has a very long history of its own. Entering history as two manors, the area became a hunting forest, and a Royal Park. For almost 400 years this prevented the area from changing or developing to any great extent, and the amount of agriculture that was allowed in the forest was very small.

In the 17th century, however, Toxteth’s park status was removed, and first farmers, then industrialists, moved in to take advantage of the newly available land. With industry came residential areas, and soon Toxteth was filling with the terraces it is still largely known for today. Many of these terraces were unfit for habitation, and slum clearance began before the 19th century was over. In the late 20th century, more clearances took place, and this area of land next to the Mersey began to enter a new age of redevelopment, although this was not also without its critics.

In this Article

- The Landscape

- Otterspool

- Dingle

- The Prehistoric and Roman Eras

- The Medieval Period

- The End of the Park and the Rise of Agriculture

- The Rise of Industry

- New Liverpool

- Toxteth Terraces

- Residential Expansion (18th – 19th Century)

- 19th Century Growth and Expansion

- 20th Century Slum Clearance

Alternative explanations claim the name to be a derivation of Toki’s Staith, meaning the landing place of a man named Toki. This version of the definition is less favoured than the other, however.

Book

This is a reprint of a book originally from 1907, and so is an interesting artefact in its own right. It includes (some speculative!) history from the earliest times until Victoria’s era.

Website

I don’t know of a good website about general Toxteth (township) history. Could you recommend one? Please leave a comment below!

Toxteth c.1900

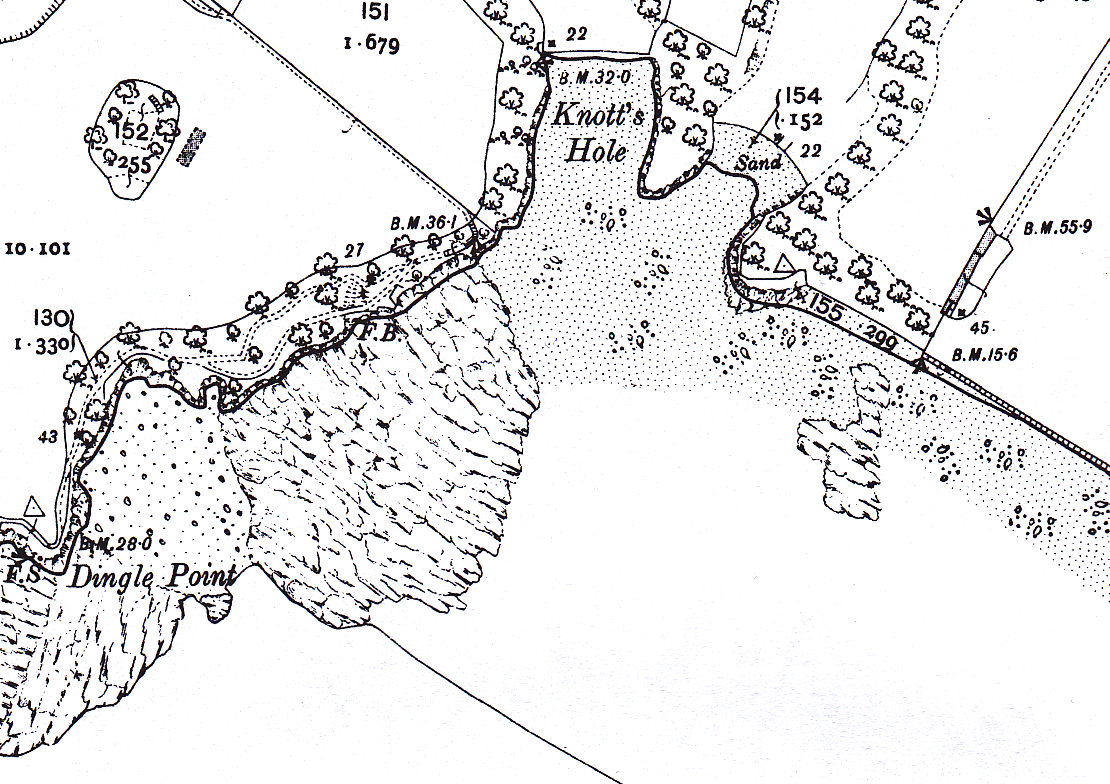

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

The Landscape of Toxteth Park

The landscape of Toxteth is undulating, rising to a peak at the north east, and there are three miles of waterfront. Toxteth lies to the south of Liverpool city centre, and before the Pool was filled in for the Old Dock travellers had to cross the Townsend Bridge, across the Moss Lake Brook, and past the Fall Well to get to the Park.

The flat areas between Parliament Street and Brownlow Hill are all that remains of the Moss Lake. The overflow from this lake, which powered a mill in the area, fed into a stream that flowed into the old Pool.

An important landmark in the area was the stream which flowed from the north east, divided into two and flowed into the Mersey in the form of the Dingle, at an inlet called Knott’s Hole, and the Otterspool, or Oskelbrook, a short distance further south.

Historically, the boundary of Toxteth Park ran from Queen’s Dock on the Mersey, down Parliament and Upper Parliament Streets, across the junction with Smithdown Road and Lodge Lane to Penny Lane, then Queen’s Drive and Aigburth Vale, before coming back to the Mersey at Otterspool.

Otterspool

Known as Osklebrok during the reign of King John, the Otterspool springs in Wavertree, and actually consists of two brooks. Otterspool was once quite a violent stream, falling 35 metres (120 feet) in just over 1km (1100 yards) many years ago. It was widened in the 19th Century for the lakes in Greenbank and Sefton Parks, and now runs under Aigburth Road at Vale and can be seen at gates of Otterspool Park.

Otterspool promenade was opened in 1950 using 30 million tonnes of rubbish and spoil from the Queensway Tunnel excavations. It was extended in 1984 with the 250 acre Garden Festival site, and is now part of the Sustrans cycle route.

Dingle

The Dingle, once known as Dickenson’s Dingle, was a stream which flowed through St Michael’s Hamlet, and the area nearby keeps the name of the old stream.

The Prehistoric and Roman Eras

Prehistory

As with the majority of Merseyside, very little is known of the Toxteth area before the Medieval period.

The Calder Stones are the oldest relics of human activity, and once formed a Neolithic burial mound in the vicinity of Calderstones Park, in the nearby township of Allerton. Another possible prehistoric monument is the Robin Hood Stone. Although its mythical connections are clear, this may be a standing stone, possibly existing in isolation or once part of the prehistoric landscape also occupied by the Calder Stones.

The Roman Occupation

The remains of a Roman road were uncovered in the 19th century near St Mary’s in Grassendale, with the route also picked up close to the river in Otterspool some time later. However, very little Roman activity is known from the area west of the road running from Chester up through Warrington and towards Carlisle. The discovery of a small number of Roman coins attests to contact between Roman and local people, but more than that we cannot say.

The Medieval Period

The Early Medieval Period (Domesday Book)

By the time of the 10th Century AD, the township of Toxteth was divided into two manors, owned by the Saxon thegnes Bernulf and Stainulf. Toxteth was recorded in Domesday as just one of a handful of coastal settlements on the banks of the Mersey, along with the manor of Smithdown (Smeedon) inland, and Garston (Gerstun) to the south. The area was part of the Hundred of West Derby, given to Roger of Poictou by William the Conqueror for his loyalty in the invasion of 1066.

King John, increasing his holdings in the area after founding the borough of Liverpool, decided to take Toxteth back into Crown hands, and by 1212 we find that Richard, son of Thurstan, had been given Thingwall in an exchange with the King, who took Toxteth and incorporated it into his hunting forest, alongside Croxteth and Simonswood. It was John who enlarged Toxteth by adding Smithdown manor to it.

The Later Medieval Period (14th Century)

By the 14th century the park was fenced around as a Royal Park. The Park had two lodges – Upper and Lower – the first of which sat at what is now the junction between Sefton Park Road and Ullet Road (the entrance to Sefton Park). The Lower Lodge may have survived, in small pieces, near Jericho Farm, Fulwood Park, into the 20th century, and may have stood on the site of Otterspool Station.

The main entrance way to the park from the north, and Liverpool, was Park Road.

The land remained as a Royal hunting forest for around 300 years.

In 1316 the land was offered to Whalley Abbey, in order that they build a monastery there. The offer was never taken up, however, and the land is recorded as being in the possession of Liverpool Castle in 1327, and in the hands of the Molyneux family by 1346.

Early Modern Toxteth (16th Century – 18th Century)

The End of the Park and the Rise of Agriculture

At the end of the 16th century, actions were taken with the aim of dis-parking Toxteth. This would have allowed the locals to graze their animals on the land, a practise which already took place to some extent. Eventually, in 1604, Toxteth was indeed disparked by James I, although the bounding wall was still in existence as late as 1671. The disparking began the first major change in the landscape since the hunting forest was created in the 14th century. The conversion to arable and pasture land progressed rapidly.

The 17th century saw a number of settlers being attracted to the area to take advantage of the new farmland, from both Liverpool itself and beyond. The land was broken up into farms, and one of the most notable communities moved into the area: the Puritans. They settled in the area around Otterspool, dubbing the stream the ‘Little Jordan’, and the area the ‘Holy Land’, a name which is still often used. The Puritans built the Ancient Chapel of Toxteth (right) in the 1610s, appointing the 15 year old Richard Mather as the master of the attached school in 1611, and preacher in 1618.

By 1800 there were four farms on land leased from Lord Molyneux: Jericho and the Three Sixes in Fulwood Park, Parr’s on Mill Street, and Rimmer’s in Dingle Lane. As exploitation of the old Park went on, this number increased and the landscape took on a much more agricultural appearance.

The Rise of Industry

Small scale industry was also a growing feature by the 17th Century.

Mather’s Dam was originally the site of a water mill on the east side of Warwick Street. This reservoir formed from a stream at the top of Upper Warwick Street, which ran across the road and down the slope to the River Mersey. The whole area here was laid out for houses once the stream ran dry in the 18th century, although the water remained standing for some years afterwards. The land between Warwick Street and Northill Street remained on a lease with the mill, but when this burned down in 1866, speculative builders moved in to develop the area.

Jackson’s Dam, sited on the shore line on what is now Sefton Street, occupied the area from the bottom of Warwick Street, across Northumberland Street. The complex included a tide mill and reservoirs. By the second half of the 18th century, industry had become the dominant feature of the landscape.

At the end of the 19th Century, the stream feeding the mill at Otterspool was beginning to run dry. Around 1772 Charles Roe leased land nearby from the Earl of Sefton and built a small copper works. At this time there were only a few scattered residences on the road from Liverpool to Aigburth. A year later Yates and Perry’s map shows seven large villas at the junction of Lodge Lane and Ullet Lane, as well as a large barn and a number of outbuildings associated with Lodge Farm. By the end of the decade requests were being made for a timber yard on Lord Sefton’s land, a sign of the future importance of the timber trade in this part of the city.

Even in the following decade the former Toxteth Park itself was still exclusively rural, although the creeping urbanisation in the north was catching up with the boundary. Even by 1775 Old Park Road, Smithdown Lane, Lodge Lane and the eastern extent of Ullet Road were the only streets in the area.

New Liverpool

In 1771 the farm of Thomas Turner was laid out for streets by the Earl of Sefton, and an Act of Parliament was obtained by the Earl for the granting out of building leases. This made it possible for a Liverpool-born builder, Cuthbert Bisbrown, who lived in Paradise Street to plan ‘New Liverpool’, a town to be built on Sefton’s lands to the south of the city.

This ambitious scheme was in competition with the cities of Bath and Edinburgh, which were both creating impressive Georgian landscapes at this time. The end result was the area known as Harrington, named after Isabella, the first Countess Sefton, and daughter of the 2nd Earl of Harrington. Unfortunately, finance at the time of the American War of Independence was scarce, and Bisbrown was bankrupt by February 1776.

Toxteth Terraces

The main streets created in the area were well built and wide, but Cuthbert’s plans never addressed the infilling of the area, which was packed with poorly built and dense blocks of dingy courts and back-to-backs. As many people as possible were crammed into the space, with no thought beyond the profit of the builders, and some of the buildings had walls of half a brick thickness.

In 1794 the land occupied by Charles Roe’s copper works was bought and converted into a pottery. In another two years this had become the Herculaneum Pottery Company of Worthington, Humble, Holland and others.

Although the pottery industry had declined in Liverpool at this time, the landscape around Toxteth provided water transport for the raw materials and products, as well as a market for the goods, and the factory did well. The surrounding district was developed to the advantage of the factory, including workshops surrounding the main site and a hamlet for the workers. The employees themselves were transported en masse from Staffordshire, well known for its expertise in the craft. The incomers were escorted into the area in November 1796, to the sound of band music and great celebration.

By 1811 there was still little further south than Northumberland Road, although the most rapid expansion in the wider region occurred in Toxteth Park, and Everton to the north, while other areas were losing population. The growing areas were Welsh heartlands in the city, attesting to the importance of this group to the growing Merseyside, and Toxteth was also becoming known as a ‘Sailortown’.

Industrial expansion kept pace with the development of Toxteth, and in 1810 the Mersey Forge was founded on Grafton Street, near flour mills standing further inland. The forge later expanded into the Mersey Steel and Iron Company, and stood near the present Toxteth docklands. Brooke and Owen’s brewery in Blair Street, only built in 1794, was dismantled in 1826 and the area covered with further terraces and courts.

The Toxteth docklands themselves were expanding in the area. Queen’s Dock was constructed in 1796. Brunswick in 1811 and Coburg Docks were built in 1840, both for the expanding timber trade. Toxteth, Harrington and Herculaneum Docks were built on or near the site of the former Herculaneum Pottery, which was dismantled in 1833. Also on the riverside were shipbuilding yards, and a ferry terminal. From 1825-35 ropewalks were established in Lodge Lane.

The timber trade was certainly beginning to dominate the area, with large timber yards along Grafton and Caryl Street. Up to 1823 few buildings could be found south of Hill Street, but the construction of Brunswick Dock (1830), changed all this. By 1835 buildings had spring up as far as Northumberland Street, with few gaps left. By the end of the next decade the street had been extended as far as Wellington Road, and Mill Street was also lined with buildings. Park Road south of the Peacock Tavern (1812), Chester Street (1815) and Windsor Street (1823) were all created in this period. The population was by now growing rapidly and more densely, fuelled by the expanding timber trade and dock expansion.

Residential Expansion (18th – 19th Century)

New Roads and More Terraces

What Picton termed “pioneer cottages” had been built on the west side of Park Road by 1803; otherwise the area had consisted of green fields and stone walls.

Larger Georgian and Victorian houses were built along Princes Road, Princes Avenue (the Boulevard) and the Georgian Quarter in Canning over the coming decades. As William Leece mentions in a comment on this site: “the expansion of the city to the south of Upper Parliament Street and east of Mill Street seems to have paused for for several years before resuming in the 1850s and 60s. The road from what is now the Rialto to Princes Park (ie Princes Avenue etc) was laid out in the 1840s, but its character looks to have been semi-rural in the early days” (see comment on the Liverpool History Map page). Mill Street is first mentioned in the Directory of this year. Parliament Street, which got its name from an Act of Parliament granted to the Earl of Sefton for its laying out, had only four houses on it in 1790, and 21 residents. Up until 1807 the street terminated at a quarry on St. James Walk, where a windmill stood. In this year it was extended until it reached boundary with West Derby. However, growth in this area remained slow, and little more was built on it until the first years of the nineteenth century.

In 1822 the area of Windsor was laid out: the area enclosed by Parliament Street, Lodge Lane, Crown Street, and Upper Stanhope Street (now Beaumont Street) began to be developed. Lands west of this, known as the Parliament Fields and belonging to the Earl of Sefton, had demanded high prices and so avoided development as late as 1875.

Park Hill Road was opened up in 1824, and South Hill Road soon afterwards. In the beginning, these were lined with the large villas of wealthy residents, but later these were replaced with rows of smaller terraces. In 1826 Upper Stanhope Street, Upper Hill Street, Chester Street and Windsor Street were purchased from Lord Sefton by the Wesleyans, and laid out Wesley, Fletcher, Clarke and Newton Streets, and a Wesleyan Chapel was built in 1827. Park Street was laid out for houses in 1826, and John Hughes purchased yet more land from Lord Sefton, before laying it out for residential streets. Land between Princes Road and Warwick Street was first built on in 1830, and nearly covered as far as Upper Hill Street within twenty years. From Upper Hill Street to Upper Warwick Street followed between 1864 to 1868.

Population increase and Migration

During the 1840s dense housing communities expanded at an incredible rate. Back-to-back terraces accounted for 65-70% of the total housing in Liverpool in the 1840s. The population never increased by less than 60% in each census between 1801 and 1851: in 1844 Irish migrants arrived in great numbers, fleeing the Potato Famine, and the building of the Greek Church on the corner of Princes Road in 1870 attested to the growing importance of the Greek community in Liverpool.

Toxteth Becomes Part of Liverpool

This massive growth in Toxteth was by no means an unusual trend. Liverpool itself was expanding as a city, and the municipal boundary took in the northern portion of the Park in 1835, along with Kirkdale, Everton and parts of West Derby. In 1895 the remaining portion became part of the city. All in all the landscape of Toxteth’s slums reflected that of any maritime town of this time concerned with commerce.

Former industrial areas were soon also given over to residential areas. Between 1849 and 1865, land south of the Welsh Congregational Church (land bought by Hughes) was converted from quarries to terraces. In 1860, land adjacent to the Liverpool and Harrington Waterworks (built in 1846) was laid out for housing, although land was slow to be built upon here. The roads were appropriately named after rivers.

19th Century Growth and Expansion

Toxteth continued to grow rapidly in the middle of the nineteenth century. Princes Road was laid out around 1846, soon after Princes Park, with Croxteth Road at around the same time. Green Heys Road was constructed in 1850, Grove Park commenced as a cul-de-sac in 1852, and Bentley Road appeared in 1862. Snowdon, Danube and Avon Street had appeared a year earlier. Northumberland and Park Street were built up around 1850, and Haslow Street in 1866 (then known as Egerton Street). The area from Park Street to Wellington Road was gradually built upon from 1850-70, close to one of the last windmills to stand in the area. To cope with the expanding population, 30 acres were set aside for Toxteth Cemetery in 1856, later enlarged to 40 acres.

However, not all the areas in Toxteth were crowding as fast as others. By 1875, from the bottom of Wellington Street and west of Grafton Street only ten cottages could be seen, and these the remnants of the Herculaneum Pottery hamlet. The area between South Hill Street and Dingle Lane were not yet built on densely: a scattering of large villas occupied the land, their gardens opening onto South Hill Grove, at the time a “verdant pasture”. The western part of this tract of land was in fact still occupied by the estate of Park Hill House. The house at this time lay on the boundary between Liverpool and Toxteth, between the rural and the commercial. Dingle was known to be “one of the most lovely bits of scenery in the neighbourhood”.

North Street (now Northill Street), High Park Street and South Street were only finally filling in by 1875 after standing empty for a time. Apart from a small number of good houses at the bottom of Upper Parliament Street, the area here was still vacant. In fact, towards the end of the nineteenth century, Toxteth, along with Everton and parts of West Derby, was losing population to other areas of Liverpool.

Parks

The cemetery was not the only open space in this part of the town. From 1864, over the next eight years, Liverpool Corporation created almost 500 acres of parkland for public use. Princes Park, laid out in 1843, was soon encircled by the large villas of the wealthy, first built on the east side. The Dingle was widened for the lake, and a red granite obelisk was erected to Richard Vaughan Yates, who had purchased the land for the park, in 1858. Otterspool was widened for the boating lakes in Sefton Park (created 1865) and Greenbank Park. Today the brook can be seen as it emerges from under Aigburth Road at the gates of Otterspool Park.

Transport

Transport became an issue for many cities in England while the inner city areas were growing with the Industrial Revolution. In 1869 the first horse-drawn tramway took passengers from the Dingle to Liverpool Town Hall. The Liverpool Overhead Railway had its southern terminus at Dingle. There were railway stations at St. James, St. Michael’s and Sefton Park.

A ferry had been proposed as early as 1775, at around the time Bisbrown was planning New Liverpool, and a tavern and landing stage were built. The tavern was known as the Tall House, due to its loftiness and isolation in this undeveloped part of the region. Unfortunately, the scheme was before its time, and was eventually abandoned. The ferry station was used as a ‘Ladies’ School’, later a tavern itself, and was demolished in 1844. In later years a ferry service began between the shore near the Tall House, taking passengers towards New Ferry.

20th Century Slum Clearance

The rapid expansion of Liverpool took its toll on the urban landscape. In 1955 the Medical Officer of Health estimated that there were 88,000 unfit dwellings in the city (45% of the total housing stock). Ten years later little had been done to tackle the problem, and the number was still 78,000. 33,000 of these houses were in Toxteth, Abercromby and Everton, and a massive programme of slum clearance was initiated. Rows and rows of uniform terraces were demolished, and replaced with high and low rise flats, new houses and maisonettes. Many people moved or were forced away from the area. 42 square miles of Liverpool were affected by the clearances, and 88 action areas were identified across Toxteth, Abercromby, Everton and Kirkdale.

Other regeneration projects began in the post-War era. Otterspool promenade was opened to the public in July 1950, constructed of 30 million tonnes of landfill and upcast from the Queensway tunnel.

However, unemployment had been increasing in the area due to containerisation of the docks. Tension existed between the black community and the local police force, and following a similar period of civil unrest in Brixton earlier that year, the Toxteth Riots broke out in July 1981.

In the wake of the violence, the Merseyside Development Corporation was formed in 1981 challenged with building the Garden Festival site: “a test of the continental model as a vehicle for the investment in resources targeting inner city development”. A certain amount of optimism gripped those in Liverpool, but many were sceptical of the new developments. 180 new homes were built on the Garden Festival site, but the New Heartlands Project, a scheme set up to administer the urban regeneration, soon became a “euphemism for ripping the heart out of the city”.

Nevertheless, in the quarter century up to 2000 a strategy based on tourism, leisure, housing and tertiary sector employment meant that the landscape along the shore, and indeed inland, was altering in a way never seen in this part of the city since the massive expansion in terraces, parkland and factories in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Further Reading

Many of the best resources for Toxteth history are the usual suspects:

- Toxteth on Wikipedia – brings together the history with the politics, geography and regeneration of the area. Also includes a list of ‘Notable Residents’.

- Township of Toxteth Park – part of the Victoria County History of Lancashire (1907) is available in full on the British History website.

- The History of the Royal and Ancient Park of Toxteth – a reprint of a Victorian history from ‘ancient times’ up to about 1905. Enjoyable mostly for the romanticism of its approach to medieval history, and loose standards when declaring bits of old stone as ‘doubtless the remains of King John’s hunting lodge’.

- The Transit of Venus (left) – a biography of Jeremiah Horrocks’s short life. Horrocks was the first to predict the transit of Venus across the Sun, and although little known, made great progress in the field of astronomy.