The former site of Liverpool’s historic Garden Festival saw the latest phase of its history in 2010, when work got under way to restore the parkland and kick-restart the building of flats on the site. But the site started life as Knott’s Hole, a little square bay surrounded by cliffs.

Knott’s Hole was a real beauty spot, later filled with rubbish and contaminated with oil. But something of a revival happened in the late 20th Century.

Perhaps the new developments will do more than previous ones to restore the pleasant air of Knott’s Hole. However, Liverpool lost a unique landscape lost long ago.

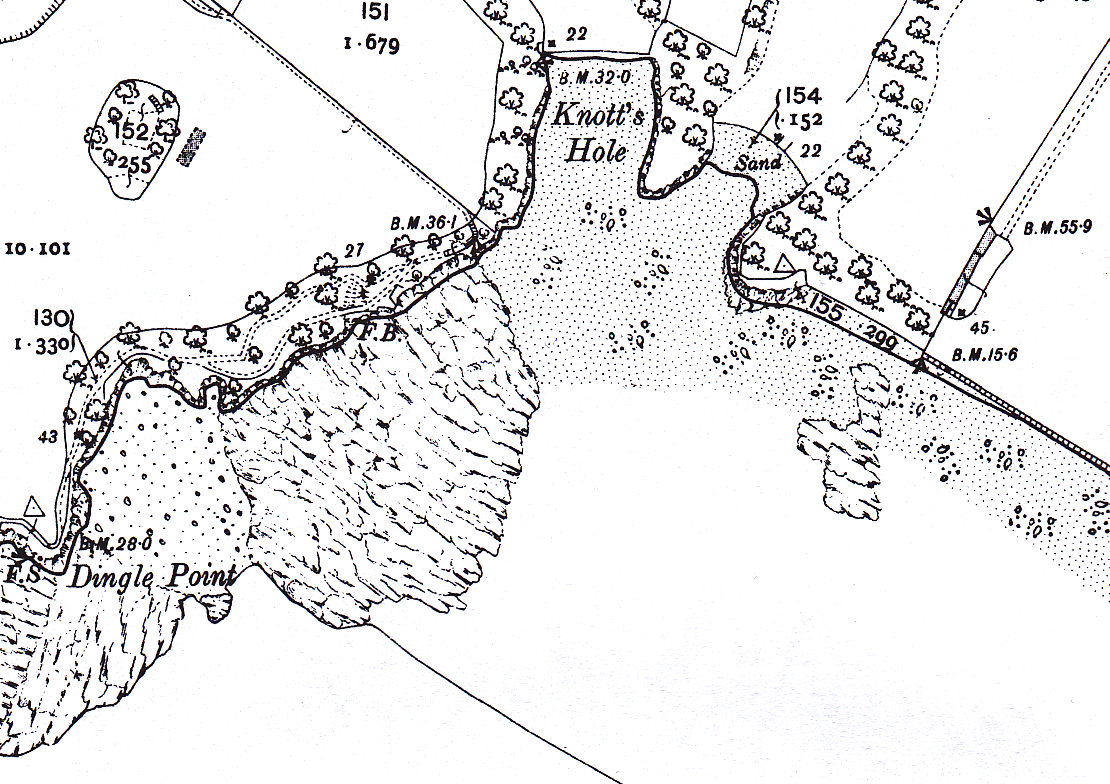

Knott’s Hole and Dingle Point in the middle of the 19th Century

The earliest Ordnance Survey maps for Liverpool are from around 1850. At this time the Dingle area was purely rural. Liverpool lay to the north west, but this was an area of large houses. The houses had vast gardens, babbling streams and a long beach close to hand.

The houses included West Dingle, the Priory and Dudley House, which sat back from Aigburth Road along narrow lanes. The beach known as Jericho Shore stretched from Knott’s Hole in the north west towards Garston in the south east. Knott’s Hole itself was a narrow bay or inlet next to where the Dingle flowed out to the Mersey. Steep rocky cliffs stood to either side, with Dingle Point to the south west.

By the time of the next map, published in 1894, Herculaneum Dock had appeared to the north. This marked the continued expansion of the docklands across the Toxteth waterfront.

Terraced houses came along, to the north east of the docks. Two hospitals appeared just inside the County Borough Boundary.

The lanes down which the large houses sat developed into a more formal settlement. St. Michael’s Hamlet, including Alwyn Street, Allington Street, Belgrave Street and St. Michael’s Road, were all built up. The Jericho Shore remained a wide beach.

Urbanisation in the 20th Century

By 1928, increasing urbanisation of the area surrounded the dingle with allotments. The area had become quite an orderly part of the grounds of West Dingle, the large house on the hillside.

Dense terraced housing was filling in the gaps not already taken up by the large villas. Toxteth and Liverpool slowly encroached on the rural outskirts.

The 1928 map also shows the south pier at Dingle Point. It is this structure which heralds the start of a complete transformation of the landscape, and one which we still look upon today.

The first development was an application to Liverpool City Council for the dumping of material dug from the Queensway Mersey Tunnel. The Council resurrected twenty-year-old plans to reclaim land from the river. In September 1929 dumping began of thousands of tonnes of rubble and household waste.

The concrete sea wall was complete by 1932, and the land behind it full by 1949.

After the War: Dingle from 1949

The 1949 map shows a handful of gas storage cylinders behind the pier. This area of the south docks was gradually becoming more and more industrialised What had once been a popular fishing destination now found its waters contaminated with oil. Fish stocks were disappearing.

More gas storage cylinders were built in the period up to 1960. Extensions to the promenade (which had opened in 1950) went northwards. The long beach of the Jericho Shore was reclaimed for building land.

Also by this time the houses on the hill had been demolished. The demolition of Dingle Head had happened before 1909.

The 1961 map shows the Otterspool river wall creeping northwards in preparation for the promenade extension. By 1964 the beach had totally disappeared, and the area was marked as Sand & Gravel.

By the late 1970s the sand and gravel too had gone, along with the gasometers. The railway remained, as did the pier, but nothing more than an embankment marked the area once covered with allotments and cut through with the channel of the Dingle. By the 1980s household waste formed the foundations of the whole area.

Unemployment, Riots, and a Garden Festival

This period was a low point in Liverpool’s history. The docks were falling empty as trade moved elsewhere. At the beginning of the 1980s the Toxteth riots drew the eyes of the country to the inner city’s social and economic problems.

For this reason Michael Heseltine, Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Minister for Merseyside’ ushered in another new use for the Dingle. The International Garden Festival took place in 1984. It was an attempt to showcase what Liverpool could do when it pooled its resources, and to spark regeneration in the area. The Garden Festival completely reshaped the landscape, whether or not it was an economic success.

The area recently landfilled was developed into extensive gardens. Where the shaded bay of Knott’s Hole once looked out on the Mersey, the Garden Festival Hall provided the focal point for the event amidst the lakes, statues and artworks. Then the Festival ended, and once again the Dingle waterfront fell into disrepair.

The years from 1984 until the turn of the Millennium were ones of little change. As planned, new housing replaced the dense terraces built in the early 20th Century. A new waterfront drive sped drivers from Garston to the city centre, past the high fences and trees of the former Garden Festival site.

In the mid 1990s Pleasure Island occupied the site, which meant a new use for the Hall and the Gardens themselves until the centre closed in 1999.

Campaigns have run to help preserve or save the Garden Festival site from ruin and unsympathetic development. Finally, in 2010, plans were submitted and accepted to build new houses and, more importantly, parkland on the site. So perhaps what began history as a secluded beach surrounded by the genteel houses of the wealthy will enjoy new life in the 21st Century as a green space for the people of Liverpool to enjoy.

Further Reading

I used the following sources to research and write this article:

Yo Liverpool – a great source of photos from its members:

Otterspool, by Mike Royden