The Calder Stones have a troubled history, even for a site that’s about 5000 years old. While it’s escaped complete destruction like many of its Irish Sea cousins, there are many of these Neolithic sites which aren’t doing too badly. Even those completely denuded of their turf, soil and/or cobble mound stand proud in fields across Wales, Ireland and Scotland, the chamber more or less intact.

The Calder Stones, on the other hand, have had the sand in their mound re-recycled for cement, and their stones (both the main stones and cobbles in the mound) crushed and used for road-building material. Then the remainder were torn from their original arrangement and turned into an aesthetically pleasing (to the owner at the time, Joseph Need Walker) ‘druidical’ circle.

Then in 1954 they were put on ‘display’ in a glass vestibule, the only remnants of the extensive glasshouses that once graced Calderstones Park. This protected them from the weather, but the enclosed glasshouse meant that their condition continued to deteriorate. Visitors could only look in through the scratched semi-opaque glass, and as a visitor attraction they were largely forgotten.

Letting silent stones speak again

One unexpected consolation prize after all this movement was that – so little being known about their original position and arrangement – there was very little further to lose in their conservation and re-presentation. All options could be put on the table.

The new home for the Calderstones opened in September 2019, and I visited in mid-October. How has the visitor experience changed? In a word, the new setting is unrecognisable compared to the old.

Whereas before the stones were locked away in a glass box, at least two metres from the viewer, you can now walk right up to them and between them.

The six surviving stones are arranged in two parallel rows. This is meant to be a nod to their original passage tomb shape, but as the relative positions of the stones are not known, the Reader Organisation and the rest of the team were free to choose the order. I’m not sure how it was decided, but if I hear about I’ll add it to this article.

It’s a great solution to the eternal archaeological reconstruction puzzle: do you pick a moment in history to reconstruct? And how do you represent the more recent history? When the Calder Stones were sat in a circle on Calderstones Road, that became part of their history, and is a point of interest to those who study the monument. To try to place the Stones in their ‘original’ configuration would not only be impossible as there are so few left, but it would be as arbitrary a choice as the circular layout.

The parallel rows acknowledge our lack of information, while reflecting the part of the history we do know. They also increase physical access to the Stones.

The new experience

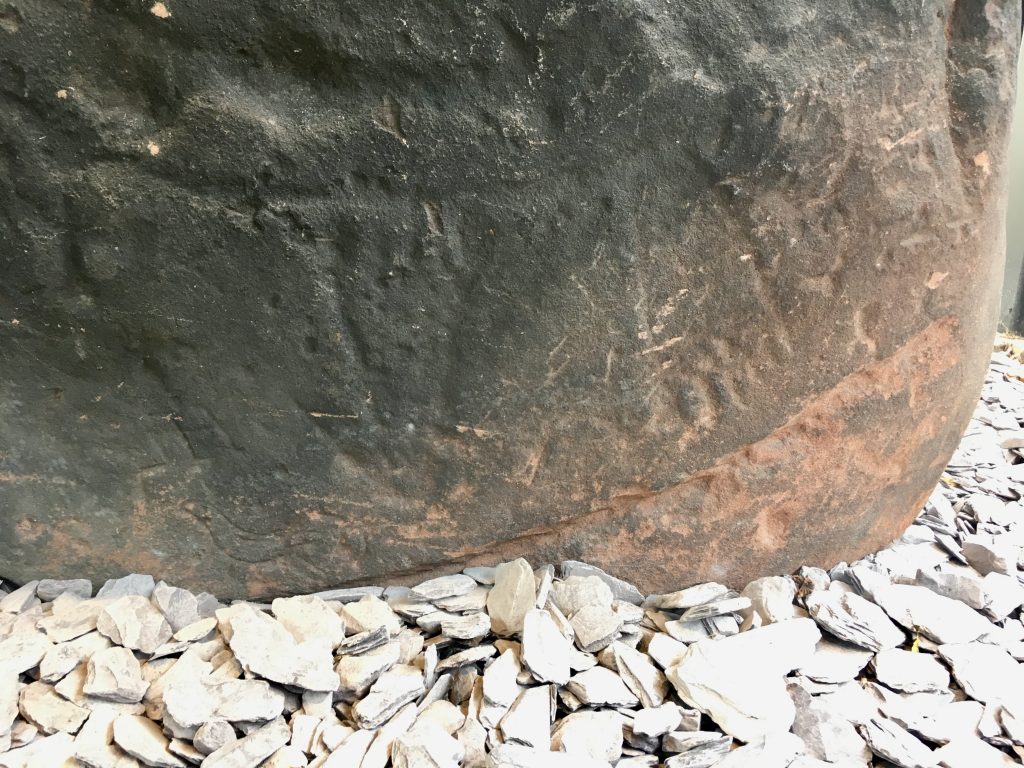

The first thing that strikes you when you arrive at the Calder Stones is how close you can get. There are no barriers between you and the rock faces, just a narrow line of slate between the path and the stone.

It goes without saying: you shouldn’t be reaching out to touch them. But you can certainly examine the stones’ surfaces, and explore them from every angle. You could try shining a torch on them from a shallow angle to highlight the relief patterns. This required special event access before.

You can walk around both sides of nearly all of the stones (one is too close to the glass, so you’ll need to go outside), examine the sides and the tops. You can truly examine the rock art.

State of the rock art

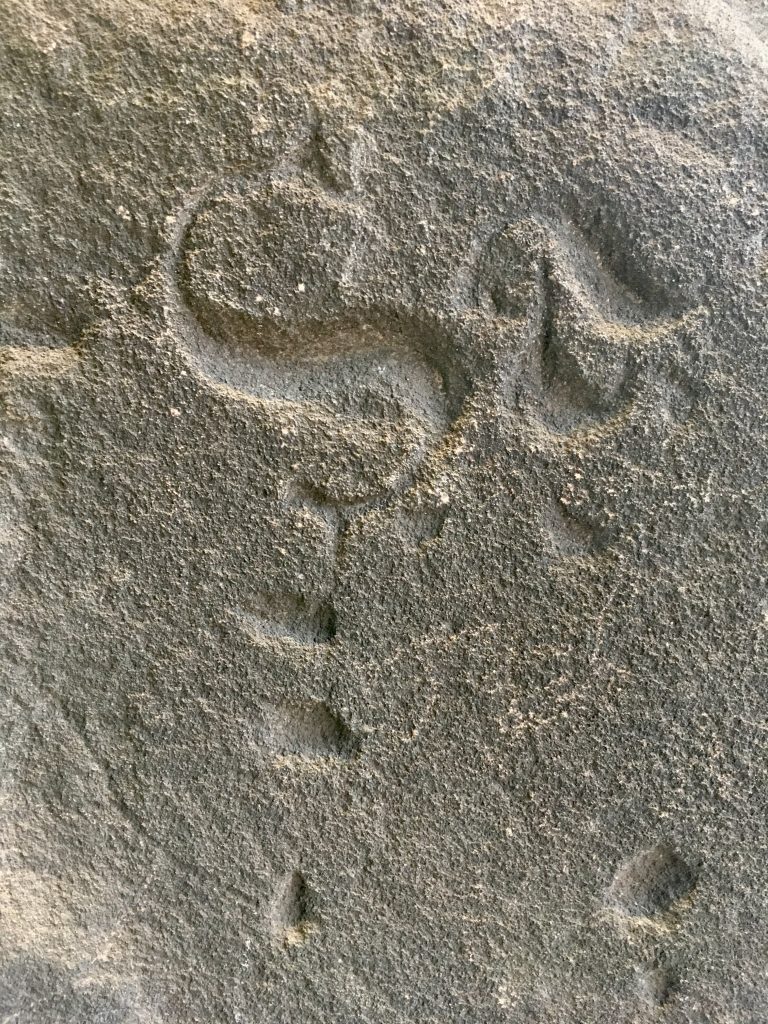

And as it’s the rock art that raises this monument above many of its relatives, this proximity makes all the difference.

No longer is the monument a pile (or ring) of stones to be looked at, gazed upon. It’s a gallery of human actions – everything from the shapes of the stones themselves, through the prehistoric cup and spiral markings, and the feet (bare and shod) from anywhere between the Neolithic, Medieval or modern periods. And don’t forget the graffiti initials!

In some way this feels closer to how the builders could have experienced it: a journey from one stone to the next, glyphs passing the eye. You’re no longer looking at the monument, you’re reading it.

I’m not sure of the decision behind the stones’ order, but it seemed to me like the stones were placed with most of the art facing inwards. This again might reflect the chamber’s original arrangement, but in any case it makes it easy to take it in in one big sweep.

This freedom to explore the stones surface leads to a tantalising possibility: will I find some new art? It’s been done, and recently! Alas, it was not to be this time, but I’m sure it won’t stop me trying each time I visit.

Here are some of my favourite carvings on the stones (click for larger versions):

You can also more closely look at the sandstone itself, for its own sake. Sandstone is a sedimentary rock, laid down at the base of an ancient sea. In south west Lancashire it’s especially red, and the ruddy layers can be seen on the edges of the stones.

It creates a link, a chain, between nature, the builders of this ancient structure and many of our buildings. Just take a look at the Anglican Cathedral, or St Peter’s Church in Woolton, nearby, and every garden wall for miles around. This is the living rock of Merseyside.

Practicalities

As soon as I posted a couple of pictures on Twitter, the archaeologist Mike Pitts noticed the blackboard imploring people not to touch the stones.

It’s vital point to raise. All heritage projects need to decide on how much access to give to visitors. Perfect conservation can always be guaranteed by completely removing visitors, and if you’re Stonehenge, complete destruction can be ensured by allowing everyone to do what they want!

At the Calder Stones, the Reader organisation have put the stones in a lockable enclosure, with close-up access to them only when the house is open (though they can be seen through the glass at all times). As I replied to Mike, there’s a certain level of trust on display. Coupled with the low level of visitors and the museum-like feel of the place, I think this trust will be repaid. The Stones will no doubt be closely monitored, as will visitor activity, and time will tell us the effects.

I’m so glad they did things this way.

Visiting the Calder Stones

Next to the Calder Stones is a small exhibition placing them in the context of world history. A time-line shows them being built before the Pyramids in Egypt, and Stonehenge in Britain. As it’s the Reader, we’re also shown when various writing scripts began their use.

Another room has an exhibition on the house and estate itself, and the aforementioned Walker family. There are replica newspapers from the time, another time-line, and a slideshow of Victorian images of Calderstones. Finally there’s a café for refreshments, and a whole park to explore!

The mansion house is open every day from 8:30am to 7pm, so go along when you can and enjoy a slice of Scouse prehistory!

Image: the Calder Stones in their new location, taken by the author.