The Calder Stones name refers these days to a group of six megaliths which once stood in a greenhouse, but now have a new home in Calderstones Park. These are the remains of a Neolithic burial chamber which once stood on the edge of the Harthill estate. The Harthill Estate later became Calderstones Park.

Before they were placed in the greenhouse in 1954, the stones stood in a circle at the entrance to the park. This was inside the roundabout on the junction between Druids Cross Road and Calderstones Road. Research by the Merseyside Archaeological Society suggests that the monument originally stood about 20 metres further west. The site is now occupied by modern flats.

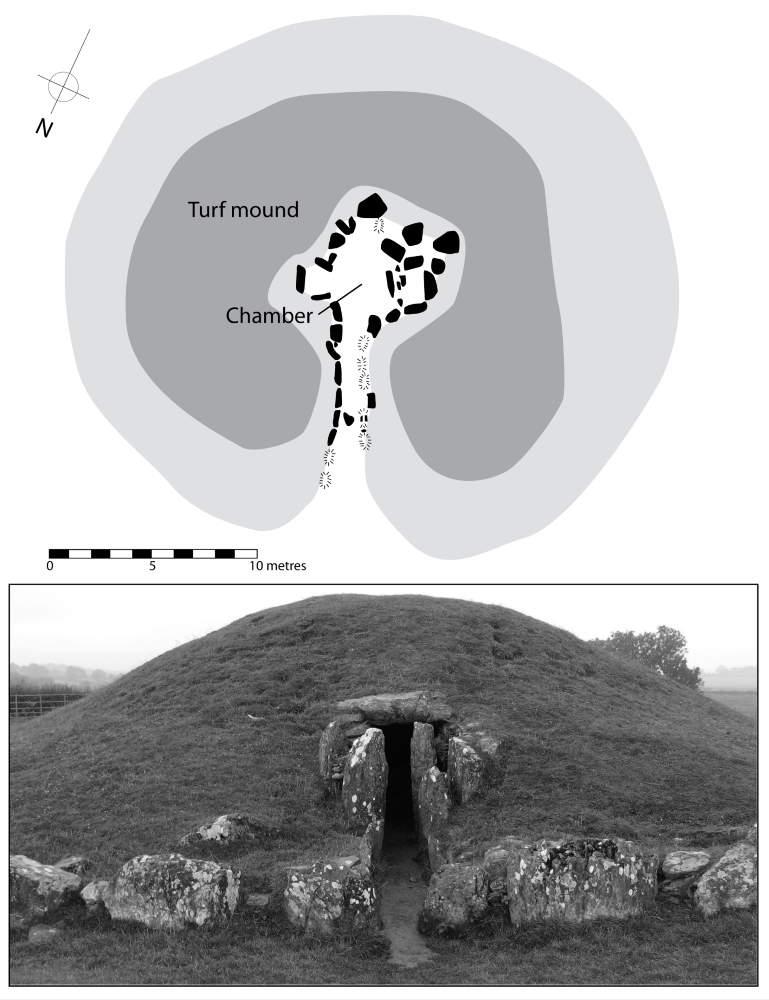

The monument would originally have seen the stones built up into a ‘box’ shape. That stone box would have had a turf and soil mound piled on top. In appearance it would have looked similar to the mound at Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey. That’s a passage tomb similar in size and date to the Calder Stones.

The demise of the Calder Stones mound was probably due to the taking of sand, and perhaps stone. These are both materials which are valued for building. Paintings show that the stones were already exposed by the 1840s. However, another image from 1825 seems to show the very last remains of the mound still visible.

Calder Stones: Meaning and use

It’s safe to say that no one really knows the full meaning or intention behind the building of the Calder Stones passage tomb. However, a look at the stones can tell us a little about it, and allow comparisons with other, better-understood sites.

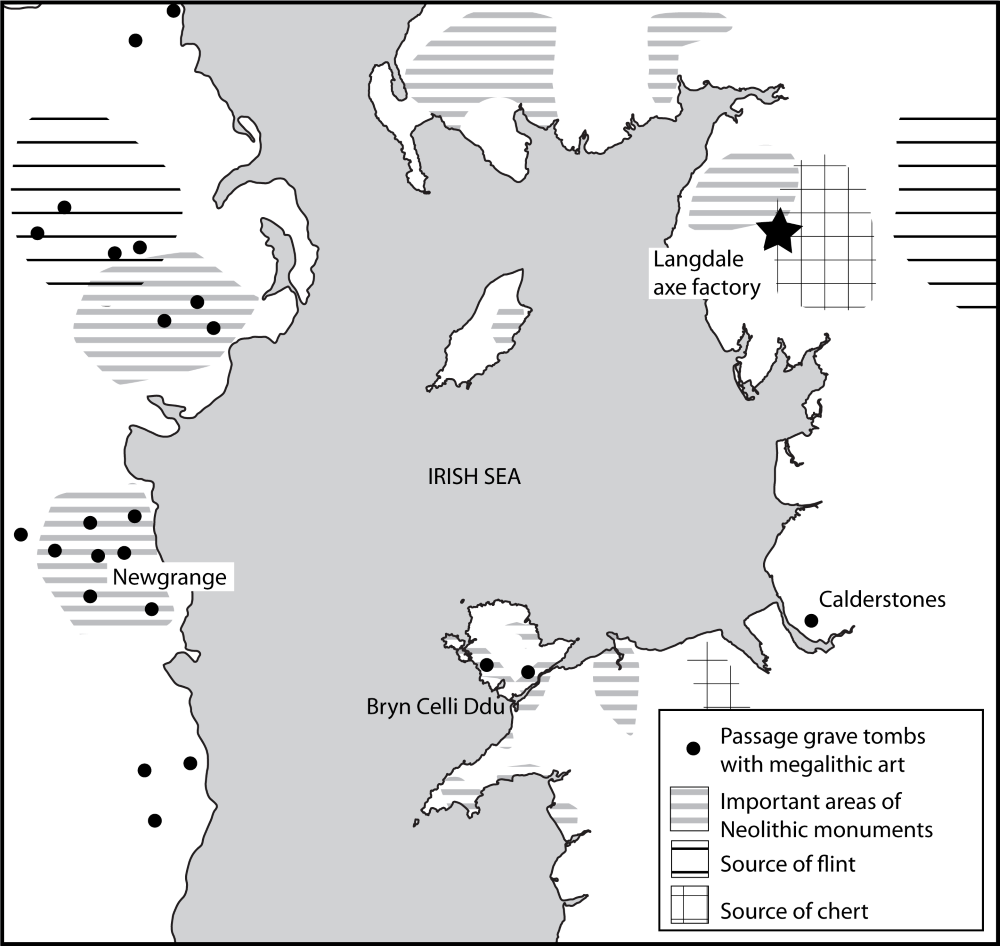

The carvings on the stones are comparable with monuments all around the Irish Sea, from Scotland, Ireland and North Wales. Some say these stones are the most decorated of their kind, and one of the dagger shaped carvings even bears a resemblance to a tomb carving in Spain!

The megalithic building traditions started in the Mediterranean area. Those traditions then made their way up the Atlantic seaboard, becoming heavily associated with north west Europe.

Secondly, a look at the landscape in which the Calder Stones sit yields further clues. The monument’s original site, like many similar tombs, is towards the top of sloping ground. The spot itself is just shy of the summit. In the Neolithic period, the tomb may have been extremely easy to see from the well-used pathways of the valley floor.

A map used in a boundary dispute in 1568 shows at least three other monuments in the area. Robin Hood’s Stone, which still exists, and the Rodger Stone, which does not, are standing stones. (The third monument, the Pikeloo Hill, also no longer exists). Examples in other parts of Europe suggest that standing stones were in valley bottoms, or on trackways. People could have used the stones as marker points. Perhaps people were expected to take a moment to gaze uphill to where the ancestors were buried. Liverpool’s two standing stones may have played this role in the Calder Stones landscape.

The Calder Stones tomb was extremely long-lived, and may have been used for up to 800 years after it was raised. It may even be the case that this tomb was one of the last of its kind, still being visited as the Bronze Age began and new religious practices emerged.

Recent developments

The stones have been sitting in a greenhouse for some decades now. It has done nothing to help preserve them. The sandstone from which they are made is prone to flaking in an environment like this. Temperature can change often and humidity is high. Projects to investigate the ancient history of the area have included the Calder Stones in their plans. As this article was being written came news that the stones should be about to move to an open air site closer to their original location.

The Reader Organisation, a reading charity which currently runs its operations from the Calderstones Mansion, intends this as part of a £2 million project to create an International Centre for Reading.

Further Reading

The Calderstones of Liverpool, by John Reppion at the Daily Grail.

As an archaeologist, I often bump into the border between the historical (especially the prehistorical) and the strange. By that I mean the paranormal, the unexplained or the mysterious. Ancient monuments like the Calder Stones are rife with legend and half-known stories. I have to admit that I love all that stuff!

But sometimes historical and archaeological knowledge is fascinatingly mysterious in its own right. For example, it has allowed John Reppion to write an incredibly comprehensive history of said Calder Stones.

The Calderstones of Liverpool collates the history, rather than prehistory, of the stones, from their earliest ‘written’ mention on a boundary dispute map of 1568 up to their relocation to the current glasshouse vestibule in the 1980s.

We also get details of associated monuments like Robin Hood’s Stone, also in Liverpool, and Barclodiad y Gawres and Bryn Celli Ddu in Anglesey, which share some important features with the Merseyside monument. Antiquarians linked them to Druids. They invented gory stories of blood running down the (in truth, natural) grooves on Robin Hood’s Stone.

Finally, John considers what might happen to the Stones in the near future. There’s a possible move from their present site, which he calls a potential “mixed blessing”. It’s certainly true that the Reader Organisation, who will be carrying out the move, have their work cut out to find the right solution. Luckily, they’re taking the time they need.

References

Journal of the Merseyside Archaeological Society, Volume 13, 2010

Greaney, M., 2013, Liverpool: a landscape history, The History Press, Stroud, p17-20

Liverpool’s Calderstones to get new home as part of £2m lottery plans, Liverpool Echo, accessed 20th January 2016

Jean Trent

says:My maiden name is Caulder my father told me when my ancestors came to America they put a u in the name . I am fascinated that this could be part of my ancestry. Do u know how I could find out?

Martin

says:Hi Jean,

That’s an intriguing fact!

There are a couple of problems to overcome first:

So your first port of call would be to work out where your Calder ancestors were living. You might have to go back to the 16th century, or even earlier, because even records back then don’t record the origins of the name.

Nevertheless, it never hurts to keep researching!

Regards,

Martin