North Liverpool is an area that I’ve become much more interested in since I started Historic Liverpool. It’s seen such changes in its time, and been home to every part of Liverpool society. Stanley Park’s a great subject for closer inspection, especially as it’s become something of a metaphor for one of the passionate divides in the city!

The park was laid out in the middle of the 19th century, alongside Newsham and Sefton Parks, to provide some much-needed green space for the citizens of Liverpool. The city at this time was a crowded and dirty place, and the poorest in society had little to gaze upon except cobbled streets, tiny houses, and their places of work.

However, Sefton and Newsham Parks had large houses built around their edge, the sale of which would go towards the cost of laying out the area, and providing facilities and buildings. Already situated in more fashionable parts of the town, these houses cemented their position as places for the wealthy, rather than those who needed them more.

Stanley Park was different, because by 1870 this part of town was already becoming ‘colonised’ by the middle and working classes, in contrast to the wealthy set who lived in central and south Liverpool. So it was to be these people who would use the park most, and influence its design and development.

The park, designed by Edward Kemp, was divided into two: an ornamental area for promenading and admiring the cleverly designed view, and an undeveloped area for recreation and sport. Stanley Park’s attraction as a place to stroll was enhanced by the raised terrace which allowed views over the tops of nearby housing and out to agricultural land, or the adjacent Anfield Cemetery. The park therefore could feel much larger than is truly was.

The presence of an undeveloped area for sports put Stanley Park firmly ‘below’ the upper classes, who rarely indulged in such unseemly activities as football. A team from the local parish church, Saint Domingo’s, played there regularly, going on to greater things with a change of name to Everton and a move out to the Anfield ground (and later Goodison Park).

The Stanley Park landscape

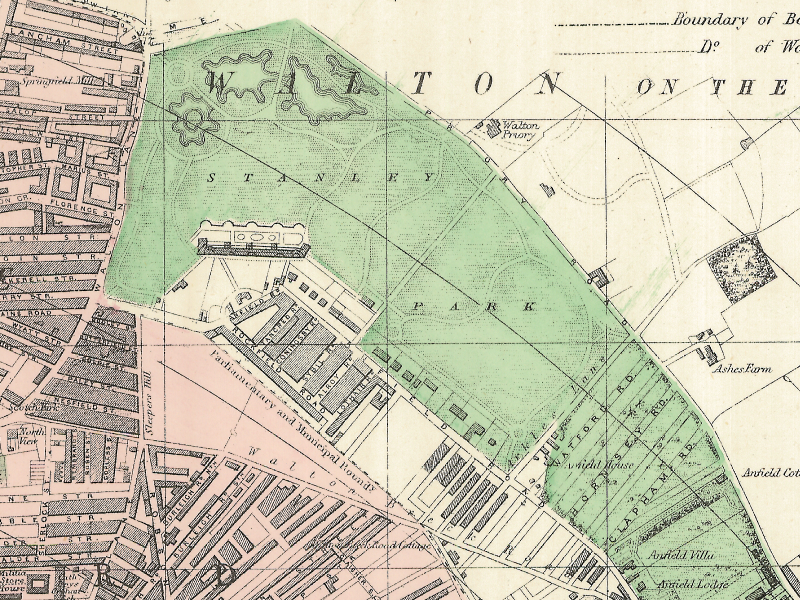

Today’s map, which is an extract from an 1890 Plan of Liverpool (North Sheet), shows the entrance buildings to Stanley Park, today occupied by housing and the Abbey Lawns Nursing Home. Behind them, to the north, can be seen the buildings which sat atop the terrace, famed for their ornamental flower beds and, as mentioned, the views across the city.

Further north again are the lakes which can still be seen, and together with the terraces these features made up the ornamental half of the park. Further east, and evident on this early map, is the undeveloped, recreational area. There are no lakes or flower beds here, just some simple paths and a wide open space in the middle.

As you can see from the full map, Stanley Park was just beginning to be engulfed by housing developments, and as the local population expanded, this facility provided a place for the locals to let off steam, or simply enjoy their valuable time off.

Just outside the municipal boundary, in a gap at the corner of Lothair Road and Anfield Road, is the vacant field used by Everton to play their matches, once the crowds became too large for the Stanley Park venue to handle. Compare it to the modern landscape.

Brian KIng

says:Thank you for the interesting article on Stanley Park. One very small point – organised football, as defined by the FA when it was formed in 1863, was initially the game of the gentleman amateur, having originated in public schools and Oxbridge. It was really with the formation of the Football League in 1887 that the rapid change began which turned it into a working man’s game. The gentlemen amateurs fought to retain control, but arguably gave up the fight around the time of World War I.

Martin

says:Hi Brian,

Thanks for adding this information. It’s very useful to understand the context of the Saturday afternoon game in its wider historical context.

Martin