The highest point in the district is St. George’s Church, with the ground sloping away rapidly to the north and west. The ridge on which the village stands extends to Low Hill and Edge Hill, and the foot of the ridge is the western boundary of the township. The centre of the old village is, unsurprisingly, Village Street.

There was a mere, later known as St. Domingo’s Pit, which was just below the Beacon, and which Mere Lane led down to. At the beginning of the 20th Century Moss Lake Brook flowed towards the town centre from Everton.

Book

This book goes with the website of the same name. It contains reminiscences of the area from current and former residents, and tonnes of photos to help you with research.

Website

This website has brilliant discussions from people who have fond memories of north Liverpool. There are also resources for the keen family historian.

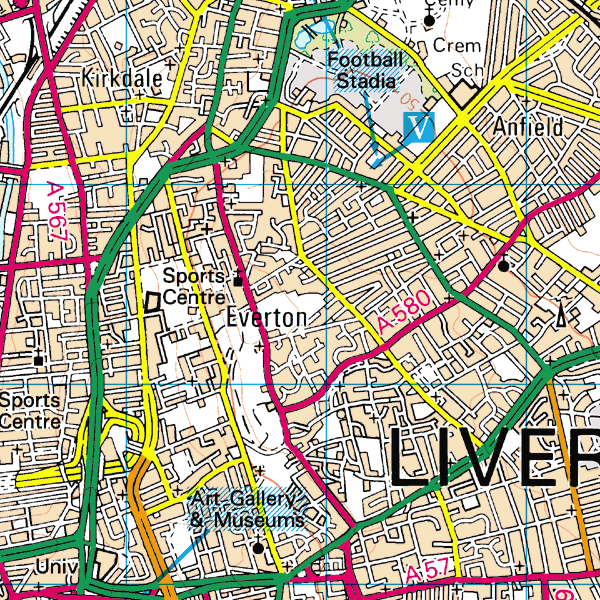

Everton c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

Transport

The main route east out of the city of Liverpool was once the road along Everton Brow, the old name of which was Causeway Lane. Halfway up the slope to the west of Everton Netherfield Lane turns to the north, with a branch leading up the hill. From the top of the village, this road led north to Everton Beacon (demolished in 1803). The road then divided, running downhill to Kirkdale and Anfield. In the fork of these two roads stood St. Domingo’s House. The roads remain as Heyworth Street and Everton Road.

After passing through the village, the road from Liverpool divides into Breck Lane, leading to Walton Breck, and another road, which again divides into roads to Newsham and West Derby respectively.

Development

Everton was one of the first areas of Liverpool popular with rich merchants who traded through the city. However, later chemical works and riverside industries arrived, and the large mansions were knocked down, and replaced with hundreds of terraces. The roads were then widened along the main routes, and tramways were serving the district by the 19th Century. As the main centre of the city decreased in population in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Everton was one of the areas which gained population in its stead. This trend was most apparent in the early 19th Century, but in Everton the pattern reversed towards 1900. Although no longer the area for the rich merchants, Everton attracted master mariners as well as working families.

As the 20th Century continued, Everton became infamous for cramped and squalid slums. Hundreds of houses were bulldozed, here and in other areas, and were replaced by equally infamous high-rise flats such as the Piggeries in Everton Park.

Industry

A large sandstone quarry occupied the northern slope of Everton Brow.

Landmarks

An old pumphouse, or bridewell, was built above the village in 1787, and was still standing in 1907. Until 1820 the shaft of a market cross stood in the open area in the middle of the village, with a sundial fixed to it. There was also a holy well in the area, but the exact location of this has been lost. Everton Beacon was a sandstone tower of two storeys, roughly 20 foot square. During Napoleonic times it was used as a semaphore station.

The Necropolis, an enclosed burial ground for Non-Conformists, is now a public garden. There was also once an open space, triangular in shape, known as Whitley Gardens, on the corner of Shaw Street and Brunswick Road.

Everton was incorporated into Liverpool in 1835.

Old Ordnance Survey Maps of Everton

1851

In the middle of the 19th Century Everton was only heavily built up to the west of Netherfield Road. The village of Everton (located at Village Street and Brow Side) was still just about discernable from the rest of the area even as the city of Liverpool encroached from the west.

New Park was marked on the 1851 Ordnance Survey map to the south of the village centre, and ‘Prince Rupert’s Cottage’ was identified. The ‘Cottage’ sat in the middle of the village green, which was stood alone in the middle of the incoming roads: Rupert Lane, Netherfield Road South, Everton Terrace and Everton Brow. Rupert House, a building commemorating the royal visit of Prince Rupert in 1644, is also marked.

Most of the township at this time was covered in large villas with back gardens or yards. These were the dwellings of the wealthy businessmen who saw moved out of the dirty city to places like Everton, Toxteth Park and Kirkdale in the 18th Century.

Along with the houses a large number of sandstone quarries are marked. These are only small and the stone for them would have been used only locally.

An area to the north east of Everton village was St. Domingo. This centres around the Church of St Domingo and also Mere Bank, a large house. St. Domingo’s Pit is also identified on the map, and the area is surrounded with the large merchant houses already mentioned. The pit was a shallow lake, or mere, from which the house no doubt got its name, along with Mere Lane which led down to the lake.

The two largest features on the map are the West Derby Union Workhouse which stood at the end of Mill Road in the east of the township, and the Zoological Gardens (complete with fireworks department!) just to the south east of this.

Finally, at the very south end of the township was the Liverpool Collegiate Institute on Shaw Street (now converted into flats) and the already dense areas making up Kensington.

1894

The next Ordnance Survey map to be published of the area was in 1894. These forty years were some of the most crucial for Liverpool, and saw the almost complete transformation of the township of Everton.

Little remained from previous years save for the main roads and Rupert’s Tower. A massive number of terraced houses had been built for the influx of people coming to find a job. Everton in particular was an area populated by Irish migrants; a high proportion of those who settled in this township were Roman Catholic. These terraces now appear to cover the entire area of the 1894 map. One of the largest gaps in this swathe of housing was the first building of the Notre Dame Catholic College.

The grounds of Rupert House (known to have been standing in 1830) by this time had a militia barracks built upon them.

1910 to 1930

While this was a very important period in world history (with the Great War and a recession) Everton does not appear to have changed much on the map. The area was still covered in dense terrace houses and courts. Churches dotted the landscape and small industrial works can be made out.

The feature marked as ‘New Haymarket’ on earlier maps is now a covered market on the newly lengthened and straightened Cazneau Street.

By 1930 the militia barracks had been turned into a recreation ground.

Soon after the end of the Second World War Britain was entered a boom time. Attempts were being made to expand Liverpool’s industry from dock working to manufacturing, and new plants like those at Speke and Aintree were the result of this. Alongside the new factories, edge-of-town suburbs were springing up to rehouse those who had been, until then, still living in the cramped Victorian streets.

During the 1950s and 60s these streets in Everton were to be demolished, but on the 1910 and 1930 maps there was no evidence of this was coming change.

1970

Although Everton was still generally a gridiron mass of roads and houses, the main arterial roads into the city had changed massively by the mid-1960s.

Scotland Road, Great Homer Street and Byrom Street had been widened and straightened, and a spiral junction had been built to take traffic into the Kingsway Tunnel.

Holes were beginning to appear in the fabric of Everton housing between Netherfield Road and Great Homer Street, north of Roscommon Street and where Campion Catholic High School now stands.

1978

By 1978 the clearances were almost complete (although the rebuilding was far from so). The space now occupied by Rupert Recreation Ground and Whitley Gardens had been cleared, but the roads were still marked on the Ordnance Survey map as rather sad dotted lines (a mirror image of when this was done on Victorian maps to denote streets in the process of being built). These large areas were later to be redeveloped as Everton Park.

2000

The transformation of Everton from its state in 1984 had now been completed. Almost all the small, straight side roads had disappeared, or been cut short and reshaped. Roads which once existed as part of the characteristic grid pattern can still be seen, but they are either dead ends or curved cul-de-sacs: Fitzclarence Street, Cochrane Street, Beau Street and Upper Beau Street are all roads marked on the 1894 map but which would be unrecognisable to their Victorian residents.

Conclusion

Everton was one of the first townships to see an influx of rich residents in the 18th and 19th Centuries. It was also one of the first to be overrun with masses of Victorian terraces which housed the dockworkers for which the city was famous.

As dock work became scarce, and well-meaning councils cleared the ‘slum housing’ after the Second World War, Everton was one of the many places where the heart was ripped out of the community and shipped the city outskirts.

While it remains one of the most deprived parts of Liverpool, it has been redeveloped with masses of green space, and still enjoys the lofty view over the city centre it was noted for in the Victoria County History.

Everton has been buffeted on the winds of change sweeping across Liverpool. How it fairs in the future will be just as dependent on Liverpool’s fortunes as it ever was.