After a long wait, the seemingly inevitable happened: Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City was removed from UNESCO’s list of sites of ‘outstanding cultural and natural heritage value’ in July 2021.

Of course, there’s no shortage of opinions on whether this was unfair, ‘incomprehensible’, or whether Liverpool needed it at all. For me, it’s raised some interesting points that should make us take stock of what heritage means to us in an ever-changing urban environment.

Reactions

The Mayor of Liverpool, Joanne Anderson, called the decision ‘incompresensible’, pointing out that millions of pounds have been poured into conserving historic buildings. The number of buildings on English Heritage’s At Risk Register fell from 17% to 2.5%. So how could the Site have possibly ‘deteriorated’?

There has been more than one suggestion that UNESCO would rather see derelict docks than a new Everton stadium. No doubt this is all hot-blooded reaction on the day, but it points to some misunderstandings about what constitutes a World Heritage Site (especially this one).

Mercantile City

Liverpool was designated a World Heritage Site in 2004 because of its role in the development of trade, transport and industry during the Industrial Revolution. This role, as I hope this very website gets across, is imprinted in the very landscape of the Victorian city. In addition to this, much of the physical fabric of these pioneering days – canals, railways, warehouses, docks – were and are still in existence, albeit some in much need of conservation work.

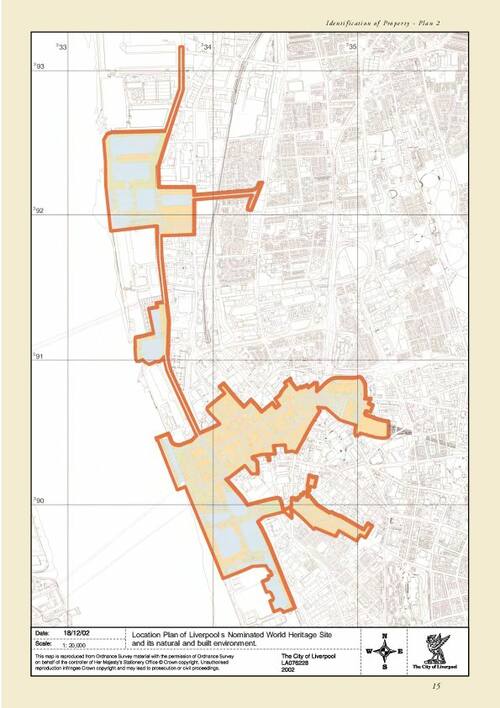

There were six areas that made up the WHS, from the Pier Head, to St George’s Plateau, to Stanley Dock. It was the integrity of this collection that formed the physical city, and the WHS City.

Buildings vs landscape preservation

I believe the very nature of this designation doomed Liverpool’s WHS status from the start. Few other WHSs will have the geographical spread of Liverpool’s, or the variety. The Pyramids, the Taj Mahal and the Great Barrier Reef don’t have a living conurbation in the middle of them – intertwined with them – requiring such a balancing act for those in power. Add to that the location of the north docks close to an area of economic disadvantage, and you have a recipe for disaster.

In fact, the economic decline of Kirkdale and Bootle can in part be attributed to their close relationship with the declining importance of those very docks. The deprivation is part of the historic chronology of the World Heritage Site. But no one’s proposing we preserve that too.

Joanne Anderson’s (and others’) appeals to UNESCO that Liverpool has made great strides in preserving individual buildings all over the WHS is addressing only part of the problem. Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City is a landscape, not just a collection of nice old buildings. The docklands are a system, not a disconnected series of piers, quays and warehouses. You can’t fill in a dock and say ‘well, we have dozens more’, any more than you can remove the Liver Birds from their perches and say ‘well, 98% of the building is still there, what’s the problem?’.

If you think this is a prelude to saying that Liverpool deserved to lose its World Heritage Status, then you’re right, and you’re wrong.

Still historic

Liverpool’s importance to global history is in many ways abstract: trade, movement, philanthropy, economics. These things are embodied in the historic buildings, and the buildings are essential to that history too, and Liverpool as a place will always be ‘historic’. But it is also very hard to capture that in boundaries drawn on a map. That goes doubly for the city’s impact on the world of music and sport. Are the Beatles any less influential today because the Cavern was demolished back in the 1970s?

We will, hopefully, always be able to enjoy Liverpool’s built legacy: the Stanley Dock warehouse, the dock wall, the Leeds Liverpool Canal, the Three Graces, St George’s Hall. The Old Dock was never so accessible a heritage site until Liverpool ONE was completed. And local campaigners continue their sterling work to promote re-use instead of redevelopment of old buildings. That’s the success that Mayor Anderson is talking about, and rightly so. But it misses so much.

UNESCO and heritage

Liverpool’s World Heritage Site was put right in the middle of not only a modern and ever-changing city but a geography that needed and needs development and change. See the aforementioned deprivation of north Liverpool.

UNESCO doesn’t need, and can’t be expected, to take into account the economic needs of the places it designates. It just decides whether a place is ‘significant’. It’s a similar case on the national level for English Heritage. Many condemned EH’s statement that Everton’s new stadium would destroy heritage, in the form of Bramley Moore dock. But what else could EH do? It wasn’t their job to weigh up the pros and cons of the development – that’s for the planning system. EH are purely advisors. Don’t shoot the messenger.

Regional Mayor Steve Rotherham said, about the World Heritage Site: “Places like Liverpool should not be faced with the binary choice between maintaining heritage status or regenerating left-behind communities and the wealth of jobs and opportunities that come with it”. I think he misunderstands the situation. When the existing heritage-status building stock can be re-used to benefit the left-behind communities, then there is no binary choice. But if the existing landscape and its buildings cannot do this job, then there has to be this binary choice, and you have to make the difficult decision. In Liverpool, these two situations were too knottily bound together, given the hige area covered.

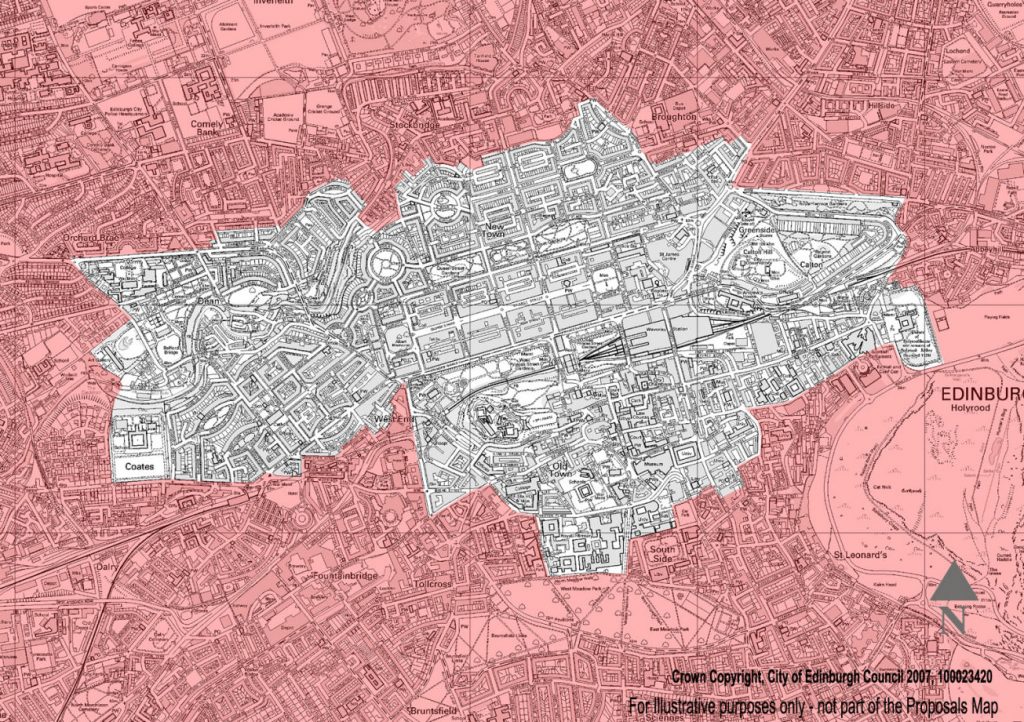

And so the problem that UNESCO unwittingly created was that the Liverpool WHS was in an impossible bind. Compare it to something like Edinburgh city centre, also a WHS. It’s a coherent landscape of the New and Old Towns, much more coherent than Liverpool’s, and one in which it is much easier to say no to development: it’s unlikely that you’d want to erect a new skyscraper or stadium in the middle of the Georgian landscape.

Likewise in Bath, in the Stonehenge landscape, or the town of Ironbridge. ‘Preservation in aspic’ is a frequently used derisive comment on heritage preservation, but these other WHSs can afford such an approach much more readily than Liverpool.

Liverpool and preservation

So where does that leave us today, with this decision?

I think it should remind us all – UNESCO included – that a World Heritage Site designation brings with it a certain set of responsibilities. If a landscape is ‘historically important’ then great changes to it will naturally reduce that importance, especially given that modern developments are unlikely to be part and parcel of that historic story.

In a tight-knit and consistent landscape like Edinburgh, or a deeply rural one like Stonehenge, development, and the demands of the people there, are of a vastly different nature to that in a city like Liverpool. These are places that we are very likely to decide that we want to keep much as they are.

But Liverpool is another kettle of fish: there are gaps (or very narrow bridges) in the WHS, and kinks in its boundaries. It stretches for miles and miles, across derelict docks and unused and crumbling buildings. This can’t be approached in the same way as would, say, Blenheim Palace. As the mayor’s World Heritage Taskforce put it: “Liverpool is not a monument or a museum but a rapidly changing city”. Exactly.

Landscape history

As with many things on this site, landscape is crucial, and a landscape is much more than a collection of places or buildings or streets.

I feel that Liverpool’s economic needs were, from the start, fated to lock horns with the demands of heritage preservation. I’m glad the designation was given, and that 17 years were enjoyed under its umbrella. But I’m starting to think that the Maritime Mercantile City should act as a note of caution to UNESCO – and those bidding for a place on the list – about the consequences of designating a landscape like Merseyside.

For bidders: would a designation fit well with the landscape as it is? Will it inferfere with other processes? Have you chosen the most suitable boundaries for the bid? Could you improve them?

There’s no doubt that Liverpool’s north docks were instrumental in the Industrial Revolution, but they are never going to be in-use docks again – was there ever a way that heritage status of any kind was going to sit well with them and their future?

Should Liverpool be a World Heritage Site?

The loss of World Heritage Status felt a little inevitable, and was the end of a long string of conflicts between UNESCO and the city. Gaining the status brought attention, investment and business to the area. It also highlighted the responsibilities that must come with it, and brought to light the opportunities that must be given up, or curtailed.

Losing the status offers the opportunity to do those things we want and need, but felt we couldn’t. Let’s hope that those who propose the next steps of the development in Liverpool City Centre do the right thing, and create a city of the 21st century we can all be proud of, WHS or not.

Image: EPW003061 ENGLAND (1920). Canada Dock, Huskisson Dock and the Sandon Half Tide Dock, Liverpool, from the south-west, 1920, from Britain from Above. © Historic England

Ron Jones

says:Excellent summation of the situation Martin. It might be the end of Liverpool as a World Heritage City but no lessons will be learned: it will continue to do what it has always done throughout the ages, namely destroy its heritage. To the best of my knowledge, nothing exists from medieval times apart from Childwall Church and Speke Hall, both ‘protected’ by their isolation from the city centre .

Liverpool’s built environment reached the peak of its glory during the 19th century: indeed, I would argue that Liverpool was the Victorian City par excellence. The rot really began to set in during and after the second world war and has continued unabated ever since.

The arrival of Michael Heseltine, so-called Minister for Merseyside, in the early 1980’s heralded an all to brief interlude when the Merseyside Development Corporation (MDC) was set up. The MDC ‘saved’ much of the derelict South Docks, including Albert Dock. Unfortunately, it was axed in 1998 before it could really get to grips with the increasingly redundant North Docks. This was left to the Port’s new owners Peel which took over ownership of the entire Mersey Docks in 2005.

Despite Peel’s many promises, it has an abysmal track record of preserving the heritage of its docklands and the actions of its billionaire owners appear to be motivated entirely by how much money they can make out of the land. It is this conflict of interests, i.e. the quest for naked profit versus sensitive redevelopment, which at the same time conserves Liverpool’s maritime heritage as far as possible, that lies at the heart of the decision to strip the city of its World Heritage status.

Martin Greaney

says:Hi Ron,

Yes, I totally agree. Peel having a monopoly on the sites most in need of (sensitive, heritage-led) development seems to be a big part of the issue. A better way forward would be piecemeal development starting at the south end and working northwards as demand develops. But no, we get one giant egocentric new city tacked on edge of Liverpool, with no evidence that anyone wants it. And then that becomes “we can’t have nice things” when UNESCO or others (English Heritage) point out that it will destroy historic building fabric and views.

I don’t think dialogue between heritage bodies and developers is ever as good as it needs to be, but it’s so wrong that this leads to zero development or a loss of designation. It feels like both sides are trying to take hostages, but that’s probably inaccurate.

My fear is that the feeling of ‘freedom to develop’ (which is falsely seen as new) will lead to poor quality development, not just for heritage.

Albert Dock, Waterloo Dock and the rest show what can be done. I have my fingers crossed, but my eyes open.

Best wishes,

Martin

Ron Jones

says:Hi Martin

Agree with you. I didn’t make it clear in my earlier response that my comments related mainly to the North Docks because the big falling out has largely been about that area. You mention Waterloo Dock. Whilst the dock was regenerated during the Merseyside Development Corporation’s tenure, it unfortunately now falls within Peel’s remit and guess what? They wanted to fill in the dock between the historic former grain warehouses and the Mersey with a new development of 646 flats in four massive 10-storey blocks. The long-time residents of the apartments in the restored warehouse were not best pleased and launched a “Save the Waterloo Dock” campaign. Peel’s developers have now watered down the scheme to 330 flats but that still doesn’t meet the residents’ core objections. The fight continues.

Eileen Rasmussen

says:I,m outraged how could this happen the citizens of Liverpool should be up in arms over this slap in the face.

is there more to this than we are being told !!

Does this commite have anothe city to take the place of Liverpool !!

Im a Liverpudlian liveing California for the past fifty years,, visit every year, until covid

to me its still a great acity with a lot to offer.

Hang in there this may turn around.

Good Luck

eileen Easmussen

says:the residents of Liverpool should be up in arms over this disgracful let down

is there more to it than meets the eye there excuses are just not enough to do this to a magnificent city with some of the most beautiful buildings in the counytry more than some in London.

There excuse jsut doesnt cut it, fight on and good luck

William Elder

says:Perhaps it would be simpler to redefine the boundary of the old WHS to exclude the north docks, which currently offer no semblance of ‘heritage’ as they are just a collection of derelict sites. Liverpool desperately needs development here to secure its (and its residents) economic future.

As a Liverpool resident, the wonder of Liverpool resides in the area immediately surrounding the three graces. I would of thought that the WHS committee (who apparently haven’t even visited Liverpool in the past 10 years) would be more concerned with the building of a black glass office block and a string of hotels plus an ugly multi-storey car park right on the waterfont.

GERALD MURPHY

says:It has to be said that our Council appointments and Peel Holdings directors have been to blame, but so many others with irons in the fire, axes to grind and other related interesting have also been sadly remiss.

At the heart lies hubris. Once our city came to see its reflection in the pool it fell in love with itself, particularly with what it thought was its most endearing feature, it’s schadenfreude and its mistrust of educated advice.

That’s not to say there was much of that about. I’ve never met an authority on industrial, mercantile or popular cultural heritage management within the City boundaries. The extent of misinformation and disdain has been prodigious.

In a recent Facebook video, the principals directors of Cavern City Tours came together to verbally celebrate their 30 years “ownership” of the Cavern Club lease. Nothing was said of any relevance to heritage asset management and nothing saie of future planning. We can only assume therefore that no lessons have been learned and no vision for the future development exists.

We do know that government arts lockdown funding was provided for the Cavern to go “online” over the 17 months of lockdown and that over a 3 year period, one director polished off 3000 pints of beer in the bar. In this light, UNESCO has been very lenient.

Bill Elder

says:Should it not be called the New Cavern as the original was demolished/filled in a long time ago. A particular example of ‘non-heritage’ thinking?