All born-and-bred Liverpudlians (and many more people) will be aware that the city is made up of a collection of villages. The villages used to sit comfortably in their landscape, surrounded by fields, lanes, streams and hills. Over time, they were swallowed up by the emerging behemoth of Liverpool itself.

In many ways Liverpool is unique (there’s nowhere else called Speke, or Fazakerley, for example), but a little digging shows patterns in the landscape, on Merseyside as well as across England and parts of Europe.

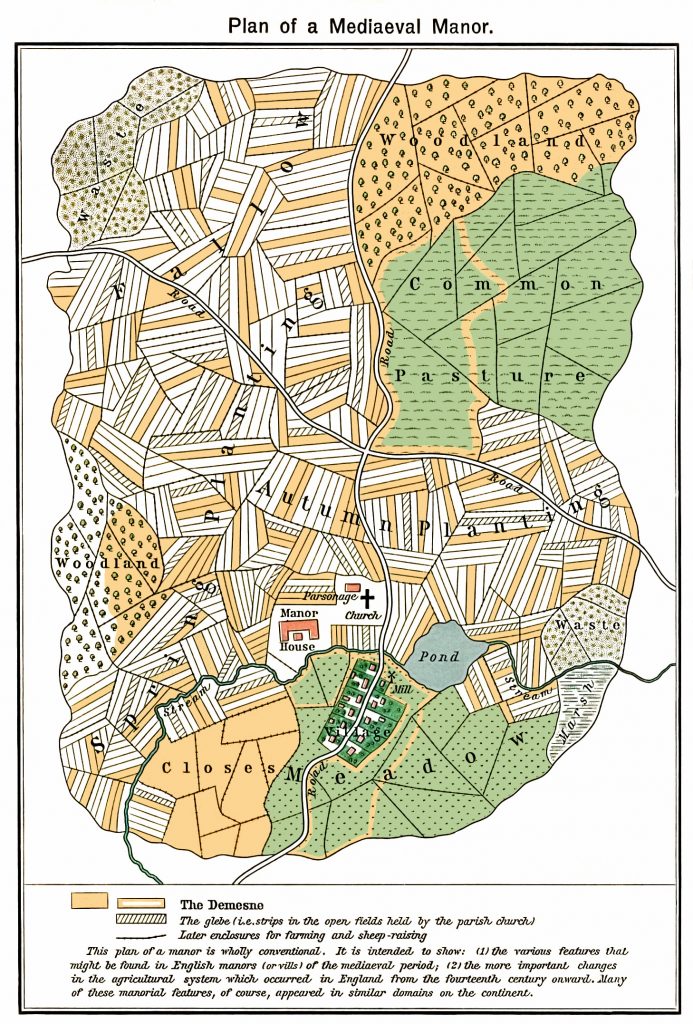

Today’s post is about a map I stumbled across on Wikipedia, and shows a stylised depiction of a medieval manor. It comes originally from the Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, published in 1911 and reissued in 1923. It’s been repeatedly cleaned up by Wikipedia’s avid editors, and I find the finished product a rather lovely work of art!

As you can see, the map shows the different areas of fields around the village centre, such as the evocatively named Common Pasture and Autumn Planting amongst others. It also has the Waste, Marshland and Woodland – it’s certainly representative!

The stream and the pond are the obvious attraction points for the original settlers, and the patterns in the fields cleverly add telling detail about the functions of the different elements of the landscape.

Model village

What strikes me about the map, however, considering the slightly ‘abstract’ nature of this diagram, is how closely it matches the suburb I grew up in: West Derby.

We have the village itself, with the town row in the centre (still so-named to this day, though just outside the centre of West Derby village). just to one edge is the village church, along with the parsonage. And right next to that, the manor house itself: the seat of power.

It’s no accident that the manor house and the church are so close together. Not only would this mean that the lord of the manor would have as short a waddle as possible to the services each Sunday, but it also ensured that the two main political forces of the medieval and later periods – church and state – were in close proximity. No doubt men of the cloth would abide closely by the lord’s wishes, seeing as he was just there, looking over their shoulder!

Shaping the landscape

Also, many manors and their villages were shaped by the lords themselves. Chatsworth, in Derbyshire, is placed close to, but just out of eyesight, from the village of Edensor. The village was moved, wholesale, by the then Duke of Devonshire between 1838 and 1842. This was partly aesthetic (it’s a beautiful village), but also partly to reinforce the sense of power wielded by the man in charge locally.

Although West Derby was never anywhere else but… there, it’s fascinating to see a pattern similar to the one that could be considered a ‘model’ for this type of settlement.

And it got me wondering: are any of Liverpool’s other suburbs long lost medieval villages? Childwall is famously a ‘church without a village’, but Woolton has a strong village centre, as did Everton. Liverpool itself was never a village in the same way, being a purpose-built market town with burgages for entrepreneurial merchants. Is the place you come from like West Derby and Everton, or is it a special case? Compare notes in the comments!