The area coming to be known as Liverpool’s Knowledge Quarter (how many quarters can one city have?) has distinct landscape characteristics. The university is just one resident in a neighbourhood of academic and other institutions.

The excellent Building a Better Society (2008, hard copy from Hive; download free PDF) by Colum Giles highlighted these. The book formed part of English Heritage’s (now Historic England) Informed Conservation series in the mid 2000s.

Around the same time, Urbed, a design and research consultancy, published Liverpool Knowledge Quarter Urban Design Framework & Public Realm Implementation Plan by Urbed (2008, free PDF) which I’d recently rediscovered buried on my hard drive. This is also a good source on the university landscape.

The topography of this part of town has played a huge part in its development. This little exploration will show how the area grew from a rural out-of-town backwater to the institutional landscape it is today.

Origins of the Knowledge Quarter

The University of Liverpool is at the centre of the Knowledge Quarter, but earns its name from the large number of other academic and research institutes in the same part of town (e.g. LIPA, School of Tropical Medicine, Eye and Ear Infirmary).

The University, the two cathedrals and their neighbours sit on high ground. In fact they’re on a ridge overlooking a steep drop towards the River Mersey.

Before the 19th century there was very little up this hill but fields. Two place names give the game away: Edge Hill and Boundary Place locate this spot as being outside of Liverpool. Even Lime Street was part-rural until 1807 (though Rodney Street and Hope Street had already been laid out by then).

The area was originally known as Mosslake Fields. As you might expect, streams and ponds characterised the place. The developers drained the land before building began. Many of the streams ran down into the Pool before the Old Dock replaced it.

The suburb

When the area was first developed, the land was used to build houses for the mercantile class looking to escape the growing town. Liverpool was becoming industrialised by the 18th century, and noxious manufacturing processes stood cheek-by-jowl with residential areas.

John Foster Senior and his son, John Foster Junior, were the two men most responsible for the new suburb. By putting houses out here in the fresh air the developers were taking advantage of Liverpool’s ambitions and the expansion of the town as a microcosm of the Empire.

The area benefited in its position in relation to the routes into town. Smithdown Lane, West Derby Road, Edge Lane and Wavertree Road are all major routes into the city to this day. They converge on the east side of Mosslake Fields. The Adelphi Hotel, like Ranelegh Gardens before it, is on the west side of the area, where the streets converge on the city centre.

When the Fosters, began their development, they built squares to act as lynchpins. Falkner Square was the first. Formerly known as Crabtree Lane, Falkner Street was a sort of continuation of Smithdown Lane coming in from the south east.

Great George Square was at the south west end, and Abercromby Square on the east, built from 1803 to 1816. Foster Sr. built Seymour Terrace, an attractive set of houses surviving behind Lime Street Station, in 1810.

You could consider another square, Islington Square near the Collegiate, as the northern extent of the scheme. However, today it doesn’t feel like it!

The first institutions

Churches, then medical and educational institutions, soon followed the houses. St James Terrace (where the Anglican Cathedral now stands) was one of Liverpool’s first parks, cementing the area as a comfortable place with the essential amenities.

The workhouse was the first large institution in the area (built in 1769, now the site of the Catholic Cathedral). This had needed much more space than the built-up town could provide, and the Corporation considered the fresh country air the best choice for its underprivileged and often sick inmates.

Liverpool’s original infirmary had moved out of the town in 1824. It moved to Brownlow Hill from its previous site on Lime Street, where St George’s Hall is today.

Once these institutions had established themselves on the hill above Liverpool, others followed. Philanthropists, wanting to promote temperance and education, set up many. Others, like the School of Tropical Medicine, were direct reflections of Liverpool’s colonial reach and the needs of its well-travelled citizens.

The landscape

A great swathe of Liverpool’s best historic buildings find their home in Mosslake Fields. The neighbourhood is a showcase of attractive residential and repurposed houses, which Urbed attributed to its single phase of development. Its ‘fine-grained’ layout is pleasant to walk through, with frontages right on the pavement.

Urbed also noted this one-plan expansion represented “[Liverpool] Corporation as agent of expressive urban design”. Something which is probably unthinkable today.

In the wars

In the twenthieth century the area suffered something of a decline. The large number of institutions here meant that, after the First World War, this part of town built a reputation as unsuitable for residence. Much of this was down to the presence of industry, and especially the busy rail lines.

After the Second World War the council needed to prevent the institutions from escaping once more, to greenfield sites outside the city. They offered them freehold of their land, which helped push out the remaining private homes from the area.

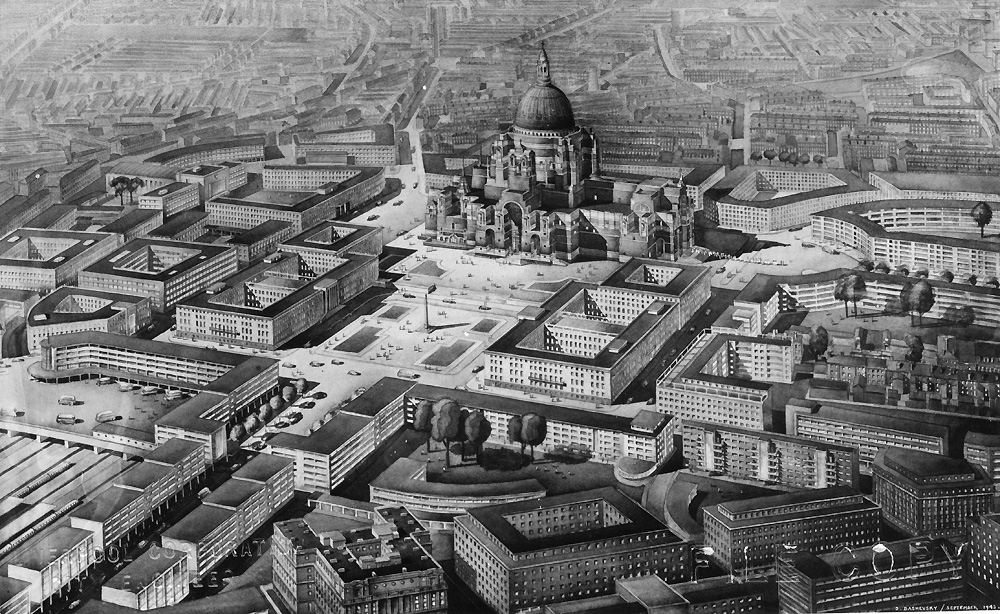

It was around this time that the post-war planners were doing their greatest damage to Liverpool’s landscape. The area around the University was redeveloped as a group of ‘singular’ buildings in the middle of open spaces.

This contrasted with the original plan (still seen on Abercromby Square and around Hope Street) of uniform streets with buildings fronting directly on to them. It punched holes in the street grid and left the area with an uneasy mixure of the old grid and the new campus.

The Holford Plan (PDF) led to a ‘broken’ campus landscape, with the new large hospital standing away and aloof from the street. Bomb sites became car parks, Islington Square vanished beneath lanes of traffic exiting the centre, and much of the space from here to Upper Parliament Street became formless. Urbed singled out particularly the way in which the old fine-grained grid produced a much better public space than the lonely concrete concourses.

The climb up Brownlow Hill or Mount Pleasant discouraged cyclists and wanderers from town. This kept the atmosphere quiet, and the academic air and vast panoramas lent the campus a detached feel. The city missed a chance to deal with inequalities of need and opportunity. This was especially damaging and distancing in the 1970s and 1980s.

The University in the 21st century

Of course, much has changed in this area since Urbed’s study in 2008. The Tall Ships, the Capital of Culture and Liverpool’s 800th birthday (not to mention Liverpool ONE) have injected new energy into the city, for better and for worse.

But new developments in the University district (OK, the ‘Knowledge Quarter‘…) have undoubtedly brought Mosslake Fields into the 21st century. It’s another stage in its life, and takes into its future a varied building stock. There are small housing schemes from the late 20th century, university buildings and still many institutions.

Only time will tell if the institutional landscape takes advantage of its unique topographical setting, or falls victim to it. Current developments will have to take this into account if they’re to constribute positively.

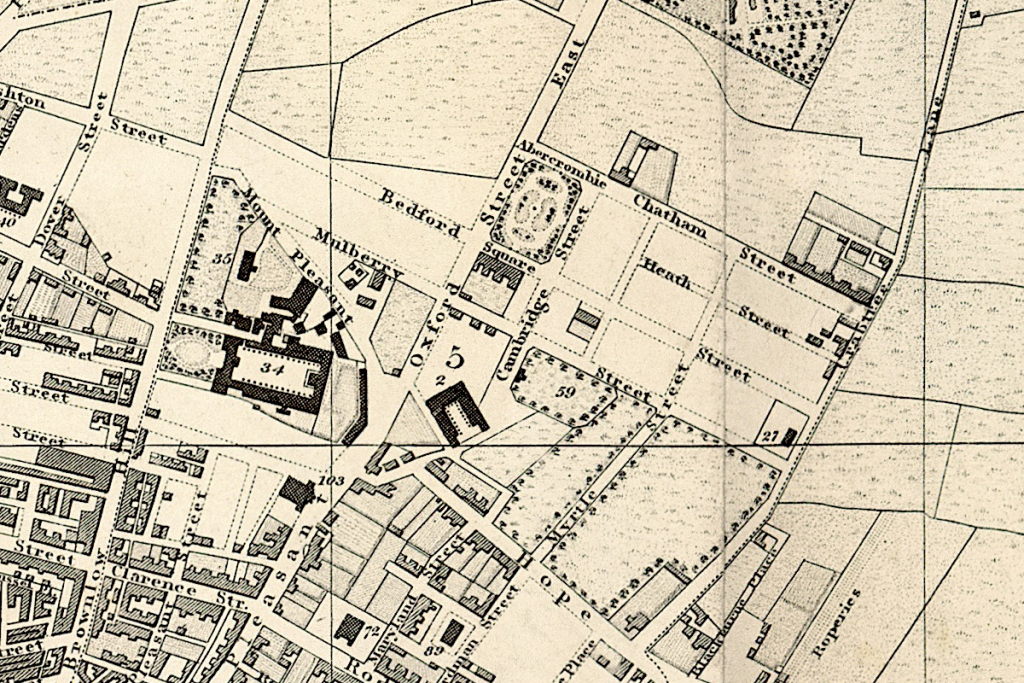

Image: Liverpool’s institutional landscape in 1892. Note everything from the Philharmonic Hall to the Liverpool Institute and the School of Art (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)