Wavertree grew up at a crossroads, on the route from Liverpool to Childwall and Gateacre, and a road branching off to Old Swan via Mill Lane. Like many parts of west Lancashire, parts of the township were once boggy (Childwall Road was once ‘Moss Pit Lane’). But Wavertree High Street runs into the village at the highest part of the township, at over 200 feet above sea level.

The landscape and economy were originally rural and agrarian, with features such as an old pack-horse track remaining (now lost (VCH)). But in the 19th and 20th centuries, as Liverpool became an important neighbour, the character of the place began to change.

The name could also be pronounced Wa’tree, and could mean a wavering tree, a clearing in a wood, or place by the common pond. The last of these alternatives makes a lot of sense considering the lake which once stood at the bottom of Mill Lane.

Note: as with many of the townships on this website, much of the information comes from one source. In the case of the history of Wavertree this is Mike Chitty’s excellent book Discovering Historic Wavertree (1999). Mike’s book is a guided tour, with fold-out maps, which takes you around the area and points out all of the points of interest along the way. It’s a very impressive volume, with research taking in the tithe maps and many other documents, and I can’t recommend it highly enough. There’s much more in there than I’ve used here, about social history and individual buildings.

If there’s a fact on this page that’s not referenced to another source, it’s from that book, and I urge you to seek it out. Generously, much of Discovering Historic Wavertree is online, on the website of the Wavertree Society, which is in itself a fantastic resource.

Book

This is a very interesting book, as it takes the form of guided walks of Wavertree, along with photographs of what you’ll see, and fold-out maps of the area as it looked 100 years ago.

Website

The Wavertree Society has been active for years, and had success in protecting the historic character of the village and High Street. News on their activities and publications is here.

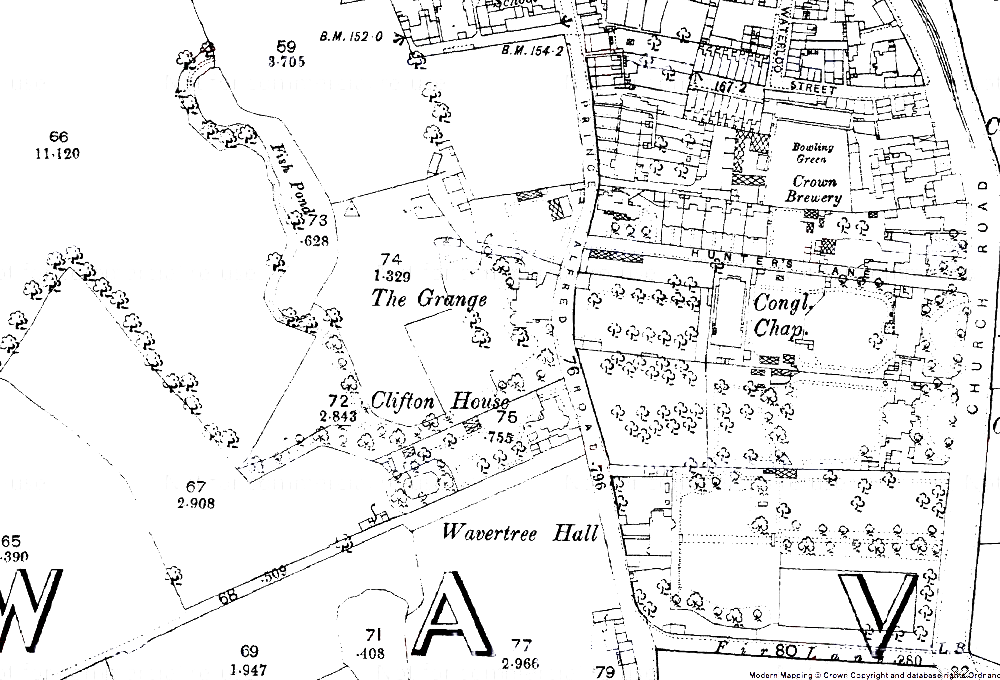

Wavertree c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

Early history of Wavertree

Little is known of Merseyside’s prehistory, except for the Calderstones and Robin Hood’s Stone, and tantalising suggestions of a ‘Pikeloo Hill’, all in south Liverpool. But we can add to this eight urns discovered in a mound on North Drive, when builders sunk the foundations for the houses. Unfortunately six were soon destroyed, but two survived, to be put into the care of Liverpool Museum. In memory of this, carved urns were added to the gable ends of numbers 29 and 31, known as Urn House and Urn Mount.

Shortly before the Norman Conquest, at the time of the death of Edward the Confessor, the manor of Wavertree was in the hands of a man called Leving, and worth 64 pence.

Rural beginnings

The village would first have built up around the junction where the Picton Clock now stands. This is still where routes to Childwall, Old Swan and Gateacre meet. The oldest buildings in Wavertree are probably those around the funeral directors’ building, marked as the ‘White Cottage’ on the 1891 OS map. The small knot of streets around here has the feel of an ancient settlement too.

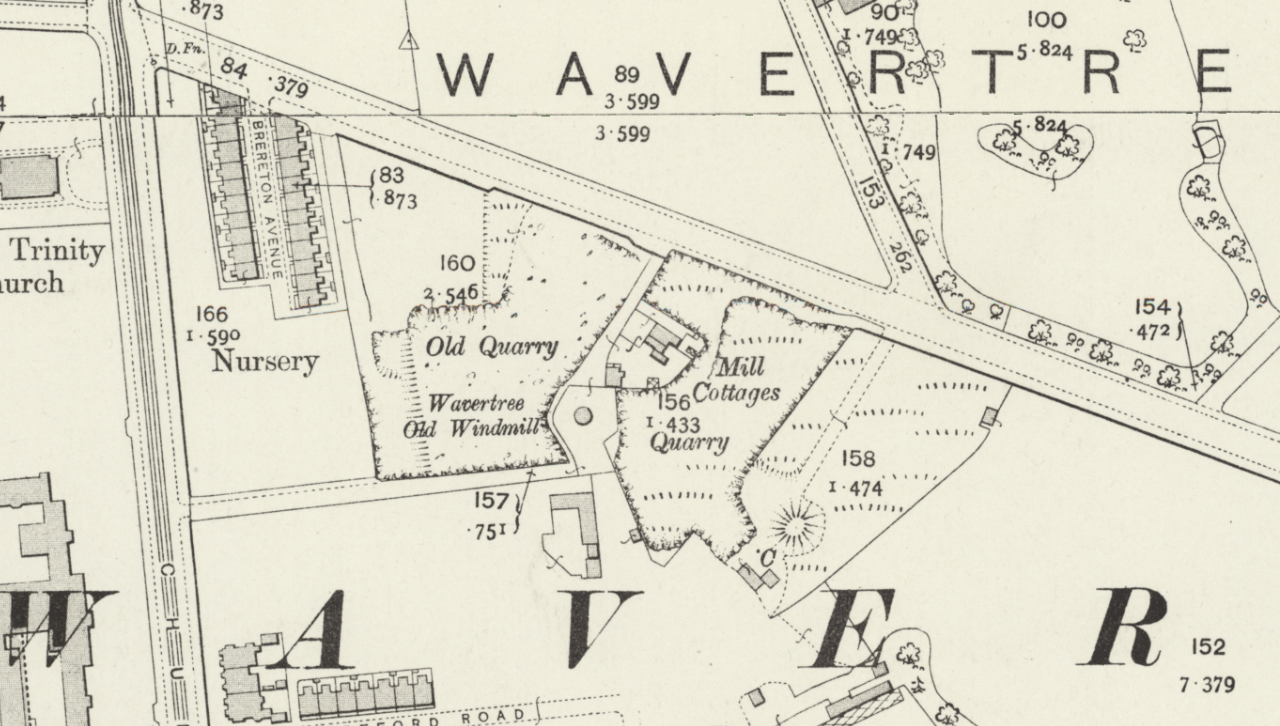

There are other clues to Wavertree’s rural beginnings. Wavertree windmill stood on the path between Beverley Road and Woolton Road, surrounded by quarries. The occupant would have been a tenant leasing the mill from the local lord, who at one time was the Marquess of Salisbury. The ‘mounting steps’ outside Holy Trinity’s church hall were probably originally a stile over a field wall.

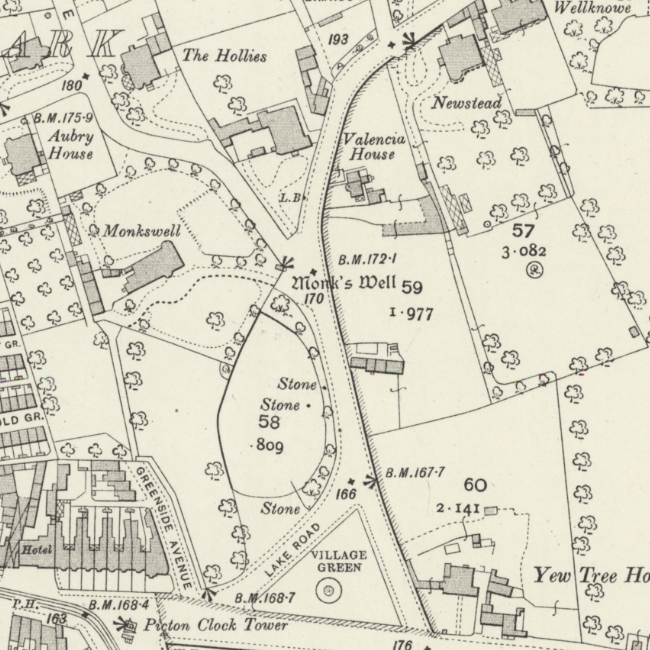

The monks’ well

There was once a lake where the playground on Mill Lane now stands. Close to this was a well, known as the Monks Well, commemorated in Monkswell Drive and Monkswell House. There’s no evidence of a religious house near here, though that doesn’t rule it out altogether. It feels telling that legends surrounded ‘tunnels’ which led from the modern position of the well (the stone cross at the junction of North Drive) to Childwall Abbey (which was never an abbey). These features seem to attract such legends.

The well was moved closer to the road because people had to cross the lawn of the nearby Lake House to get to it, and the owner was not happy with that! The well now has a sandstone cross above it with the engraving: ‘Qui non dat quot habet//Daemon infra ridet. Anno 1414’. (He who here does nought bestow, The Devil laughs at him below). Whether the date is accurate is open to question, knowing as we do that the well has been moved and altered over the years.

A pump was added to the well in 1834 to bring water up from its underground source, and the whole well is now listed.

Changing inhabitants – common land to mercantile suburb

Wavertree was once largely owned by the Marquess of Salisbury. Merestones engraved with an ‘S’ once marked out the boundary between his land and the common land. One of these stones survives at the bottom of Mill Lane.

Wavertree lays claim to the last slip of common land in Liverpool. This is the ‘green’ on which sits the lock-up. According to the Victoria County History, the Enclosure Act itself guarantees that this parcel of land will remain common.

The rest of the common land in Wavertree was enclosed in 1768. The Enclosure Act included a ban on walls over 4’6″ to make sure the wind could still get to the windmill! Oddly enough, this ban was invoked in the 1930s in an attempt to prevent the cinema being built – despite the fact that the mill was demolished nearly 30 years before!

The lock-up which sits on the green dates to 1796. Before then the local constable had to give house and board to any drunk and disorderly members of the community to sleep off their liquor. The expense was reimbursed by the parish, and so the lock-up was an investment with a long term plan to save money.

When the police station was built on the high street the lock-up became redundant. It was at risk of demolition, but Picton, the architect after whom the clock is named, campaigned successfully for it to be kept. He helped to ‘beautify’ it in 1869, which probably helped its cause, and it remains a landmark to be appreciated.

On the 1768 enclosure map there’s a ‘Tyth Barn‘ (Hist Soc Lanc Ches, 1913 – PDF) approached along a track. This is now immortalised by Tithebarn Grove off Lance Lane.

Eventually the purely rural landscape of Wavertree was overtaken by the approach of Liverpool from the west. The windmill survived through the next phase, though, as Wavertree became a suburb. It stopped operations in 1873, although was put to work now and again until 1890.

A gale damaged the structure in 1895, and it was finally pulled down in 1916. The quarries nearby were eventually filled with household waste – mostly ashes – and the footprint buried. This was uncovered in 1986 when the houses were built on the site, and some of the stonework can still be seen preserved in their front gardens.

The merchants move in

The last tenant of Wavertree windmill was Charles Taylor. Taylor owned a flour warehouse at 203 High Street, marking a crossover between the previous rural economy and a rising merchant class.

Liverpool was becoming an important neighbour in the 18th century. As the burgeoning town grew and became a dirty and crowded place, Wavertree was one of the rural places to which the wealthy escaped in the 19th century.

Cow Lane had run parallel with Church Street until a local man, Samuel R. Graves, played host to Queen Victoria’s son Alfred. Cow Lane was renamed Prince Alfred Road, and the Edinburgh pub also commemorates his visit. Clearly Wavertree’s aspirations were expanding beyond its traditional horizons.

As merchants and other wealthy families moved to Wavertree, a series of housing estates grew up to accommodate them. The Sandown estate, Olive Mount and Victoria Park (known as the Lake House Estate) all housed this new class of people. The tall garden wall of Lake House can still be seen at the end of South Drive.

The Sandown Lane estate was served by a very early postbox (installed 1865, destroyed by a firework in 2005), a reflection of its importance at a time when pillar boxes were only just becoming common. One of the most famous families on the estate were the Hornbys. Hugh Hornby lived here, and his nephew Thomas Dyson Hornby had Hornby Dock named after him. The Hornby Library in William Brown Street is named after Fred Hornby, who donated his rare books and manuscripts.

Orford Street is the counterpoint to these large estates. Chitty calls it one of the most attractive streets in the district, and it was home to teachers, artists and tradesmen who would have served the large houses. A Dr. Kenyon, whose house backed into this street, was the man behind its development for houses.

This had an effect on the High Street, which had been a residential street for the whole of its history. Businesses were started here, and the transformation to a commercial street took place across the 19th century. There was even a branch of the Bank of Liverpool here from 1886 onwards. This would have been an essential service for the merchants and business owners.

Wavertree became home to a Technical Institute (1898), library (1902) and baths (1904) all designed by Thomas Shelmerdine, even before it became part of Liverpool. These kind of institutions were part and parcel of a fashionable (and wealthy) suburb. But the jewel in the crown was the Town Hall (1872), which cemented Wavertree as an independent place. The motto engraved on the front is Sub Umbra Floresco (I flourish in the shade). It shows a candid understanding of its large and important neighbour, but at the same time a determination to be independent.

Merchant Palaces

James Allanson Picton was an architect and historian who moved to Wavertree and lived in Sandy Knowe on Mill Lane. Not only did he alter the design of the lock-up (possibly making it more acceptable to the Victorian gentry) but he also donated the Picton Clock, in memory of his wife Sarah Pooley. It purportedly stands on the site of the ‘Big Lamp’.

Olive Mount, a large sandstone house which was to become the centre of the large ‘Wavertree Cottages’ was built in the late 18th century by James Swan, a tea merchant.

One of the most lasting legacies of this time is Wavertree Playground, or the ‘Mystery’ to give it its common name. It was once the grounds of The Grange, another large merchant palace. Like many estates across Liverpool The Grange’s house was demolished, with the area likely to be developed into houses (perhaps similar to the terraces in the area around Prince Alfred Road).

But the land was bought by an anonymous city benefactor (popularly thought to be the shipping magnate Philip Holt) and donated to the city. It was given with the hope that it would be used for sports and exercise, rather than for the fashionable to promenade and ‘be seen’. This is why there are no features (lakes, flowerbeds) on the Playground like there are in Sefton and Stanley Parks.

The Industrial Revolution and the middle class

As the city of Liverpool encroached from the west, the railway cut through the township. The Liverpool-Manchester stretch of the London and North West Railway runs along the north boundary of the district. The Olive Mount cutting is a monument to early railway engineering, and Henry Footner’s Grid Iron system at Edge Hill was another pioneering system (albeit inspired by others). A northern branch line led to Bootle docks.

The Liverpool to London railway went through the township to the west, and the Liverpool tramway system extended as far as the top of High Street (Picton Clock being the terminus). There is still evidence of tramways and their setts between Wavertree Gardens and High Street .

Welsh-built byelaw houses appeared in the Northdale Road area, as they did in much of Liverpool’s surburbs. In Wavertree they were known as the ‘Railway Parish’. These houses were aimed at a lower level of income than the likes of Sandy Knowe and Olive Mount, and mark the arrival of clerks and other office workers to Wavertree.

Later residential development

Once the first few streets of smaller housing had been built, Wavertree quickly took on the appearance of a Victorian suburb. The streets opposite the Blue Coat School on Church Road began with Isaac Dilworth’s and Charles Berrington’s ‘Dovercourt’ (also known as Tudor House or even Dilworth’s Folly).

The roads themselves were not developed with such ambitious houses. Rather, they have attractive but smaller mock Tudor residences. The footpath to the former mill is preserved in the north east corner.

Wavertree Cottage Homes

At the end of the 19th century the Select Vestry bought Olive Mount house. Cottage Homes, based on the Fazakerley Cottage Homes but for housing younger people was built in the grounds and opened in 1901. The streets on the housing estate now known as Mount Royal were named after Olive Mount residents at the suggestion of the Wavertree Society.

All this expansion in Wavertree housing led to a population explosion. In 1801 there had been 860 people in the township, but by 1901 the number of residents was 25,000.

Wavertree Garden Suburb

Few people will be unfamiliar with Wavertree Garden Suburb. It’s a distinct area of housing between Queen’s Drive and Childwall Road that has its own recognisable character.

It was founded in 1910 as the Liverpool Garden Suburb by Henry Vivian, a carpenter and active trade unionist, inspired by London’s own garden suburbs. Vivian hoped that it would provide a large stock of housing for those people – clerks and office workers – who were starting to move into the area.

He wanted to give the residents a financial stake in the suburb, if only to give them an incentive to keep it well maintained. Liverpool Garden Suburb Tenants Ltd was set up, explaining why you can see ‘LGST’ on ironwork like drains and manhole covers.

The members, all residents, recieved 5% dividends on all profits. It was also hoped that the profits would fund expansion of the scheme to the currently open fields nearby. This in turn would increase the opportunities for people wishing to move out of the noisy and dirty inner city, cementing the claim reflected in its telegraph addess: ‘Antislum, Liverpool’.

The architecture of Wavertree Garden Suburb is inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement, just like Port Sunlight. The houses vary in style, but, cleverly, costs were kept low by bulk-buying elements like windows and tiles. These would be shipped around the country to other Garden Suburbs, helping maintain variability.

But despite the similarity to Lord Lever’s Wirral village, Wavertree Garden Suburb was not intended to be a standalone settlement. It was always intended to be a satellite to Liverpool, to house commuters travelling into Liverpool by tram. It’s telling that there were no shops on the estate until late in 1914. In fact, Ebenezer Howard, the pioneer of the Garden City movement, would have disapproved of the sprawl that Wavertree and its brethren represented.

After the First World War, building costs increased but rents were controlled by central government. The LGST was no longer economically viable and the houses were gradually sold to private owners. The company was wound up in 1938.

Still, the pioneering spirit of the suburb is still evident in the landscape. Chitty points out that the large side garden of number 10 is an unusual result of Liverpool’s stringent planning regulations. They stated that air circulation had to be guaranteed by building a side road at least every 150 yards. Of course, Wavertree Garden Suburb had plenty of space designed into it, but the inflexibility of the regultions meant that this concession had to be made. Secondly, there was an influence on later building design: the architecture of the more recent houses facing onto the Suburb were clearly influenced by the older stock.

Green common to green suburb

Wavertree had started out as a stop on the route out of Liverpool. It’s now a busy suburb and destination in its own right. Originally a rural settlement with a windmill and common land, it changed gradually into, first, a place for the richest members of Liverpool’s commercial sectory to move to, and later a suburb for middle class workers to commute from.

Wavertree Garden Suburb typifies this attempt to create a small slice of quiet in a busy city, and this feeling permeates the rest of the area.

Further Reading

Leach, I., 1931, The Wavertree Enclosure Act, 1768, Trans. Hist. Soc. Lancs. Chesh., vol 83: 43-59, accessed 18th August 2020.

‘Townships: Wavertree’, in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 3, ed. William Farrer and J Brownbill (London, 1907), pp. 111-112. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol3/pp111-112, accessed 4 April 2020

Maps: Where maps are generally credited to the National Library of Scotland, they come from their Online Mapping website.

Images: Unless otherwise stated, the photos are by the author and released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.