Speke has always been a large township on the banks of the Mersey. Speke village itself never grew in size like the inner suburbs of Everton and Toxteth, but the large expanses of flat land attracted industry in the 20th Century, and large housing estates and industrial complexes grew up here. However, problems associated with the rapid expansion led to trouble at the end of the century.

Some sources say the name comes from the Old English spec, meaning brushwood (Farrer & Brownbill, 1907), while others point to spic, meaning bacon (Pye, K.), and indicating the presence of pig fields. There is also the link to the surname Espec, allegedly of Norman origins. I’ve not managed to confirm whether the name came before the lands at Speke were granted.

Book

One of the many heavily illustrated books on areas of Liverpool, David Paul’s Around Speke contains before-and-after photography of Speke alongside captions detailing the changes seen.

Website

Although I haven’t found a website dedicated to Speke, this Speke Hall website contains all you’ll need to start research on this part of Liverpool. There are plenty of photos too.

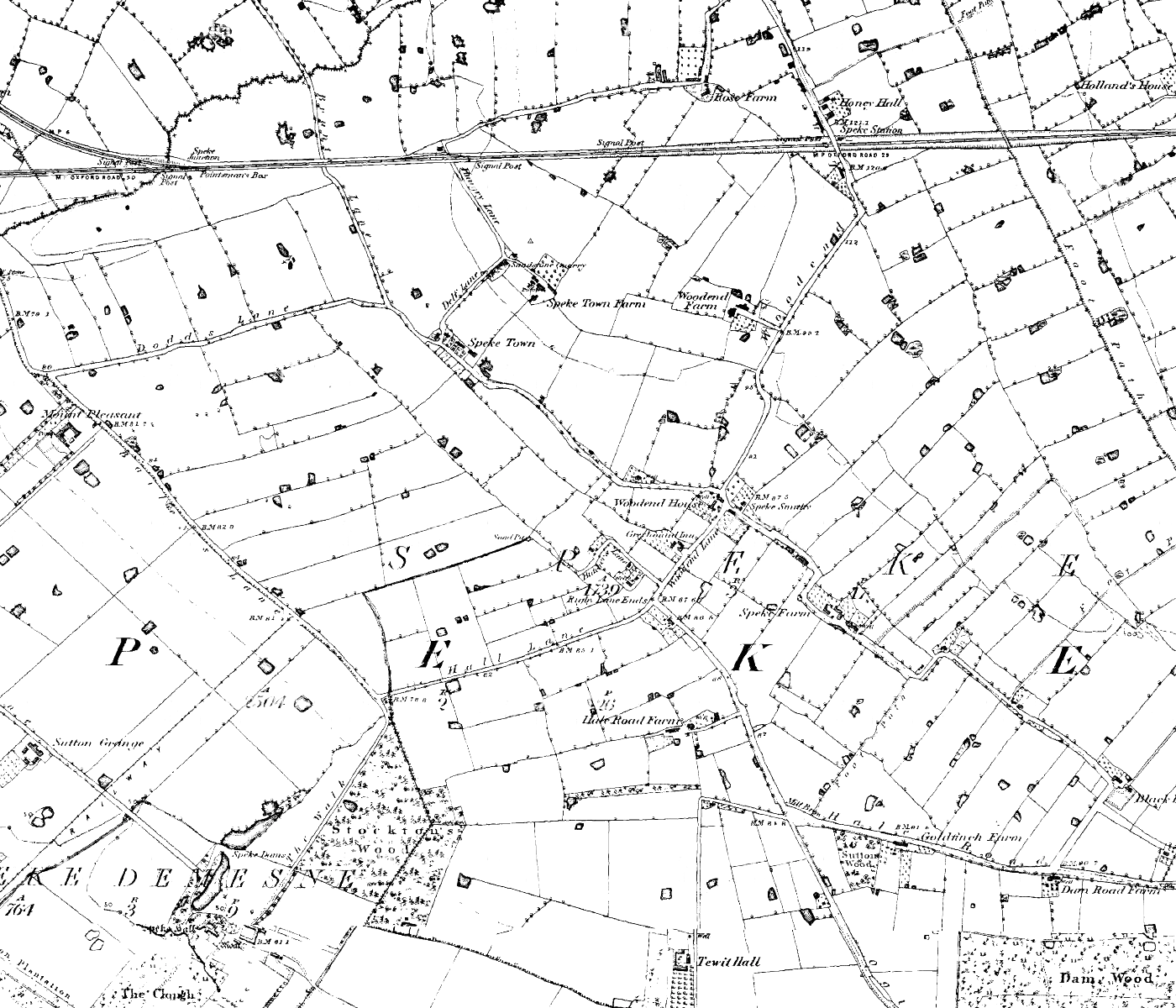

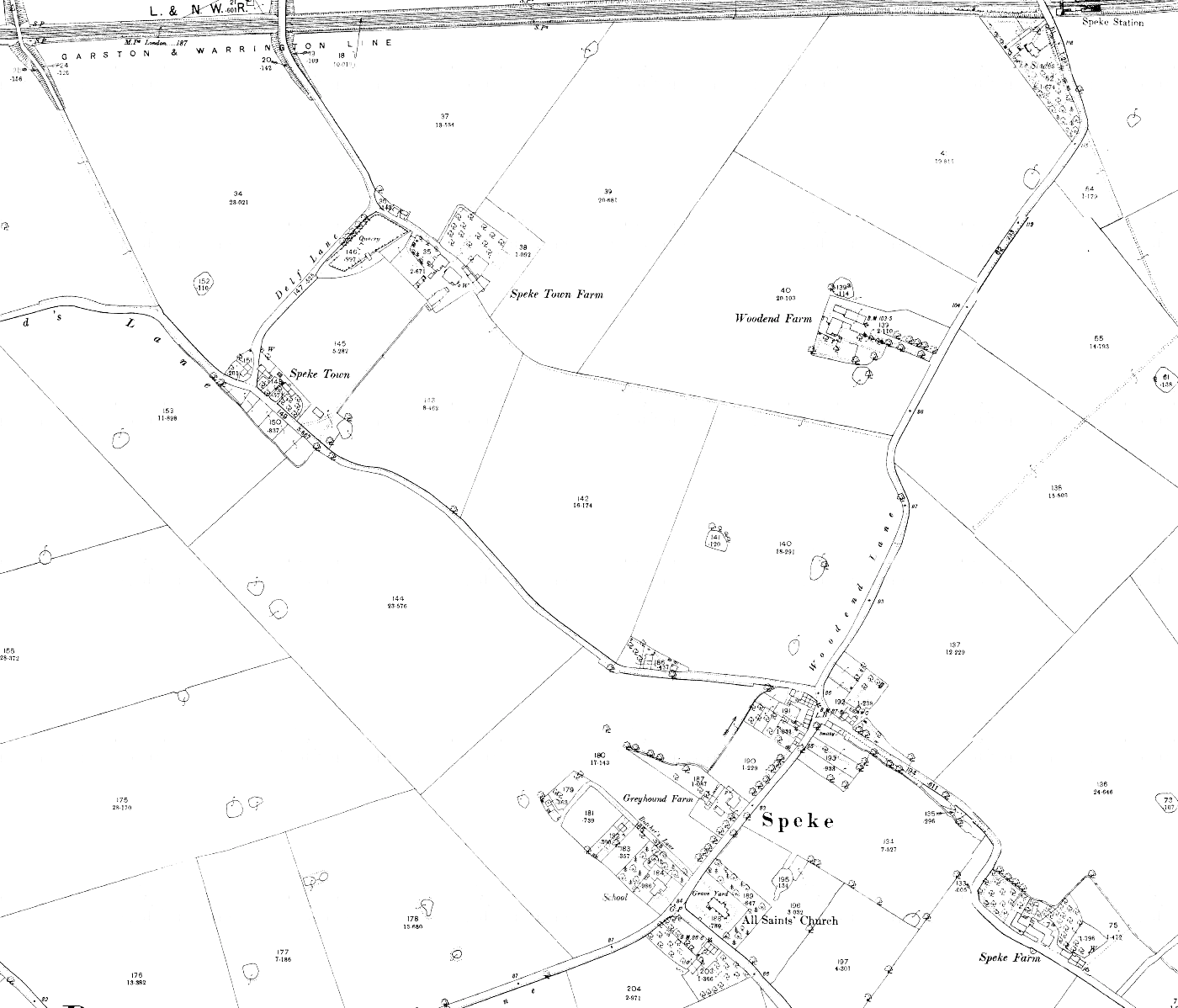

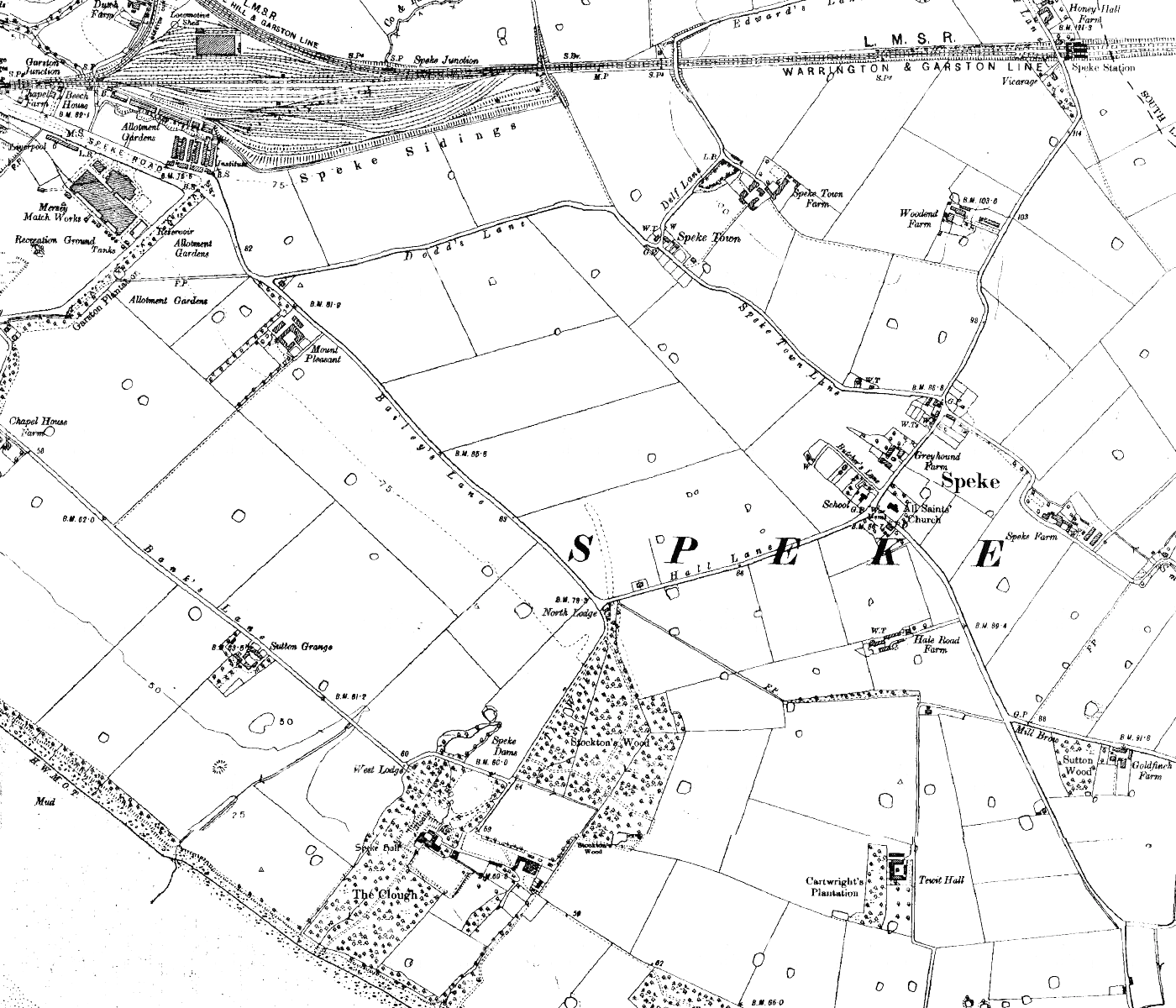

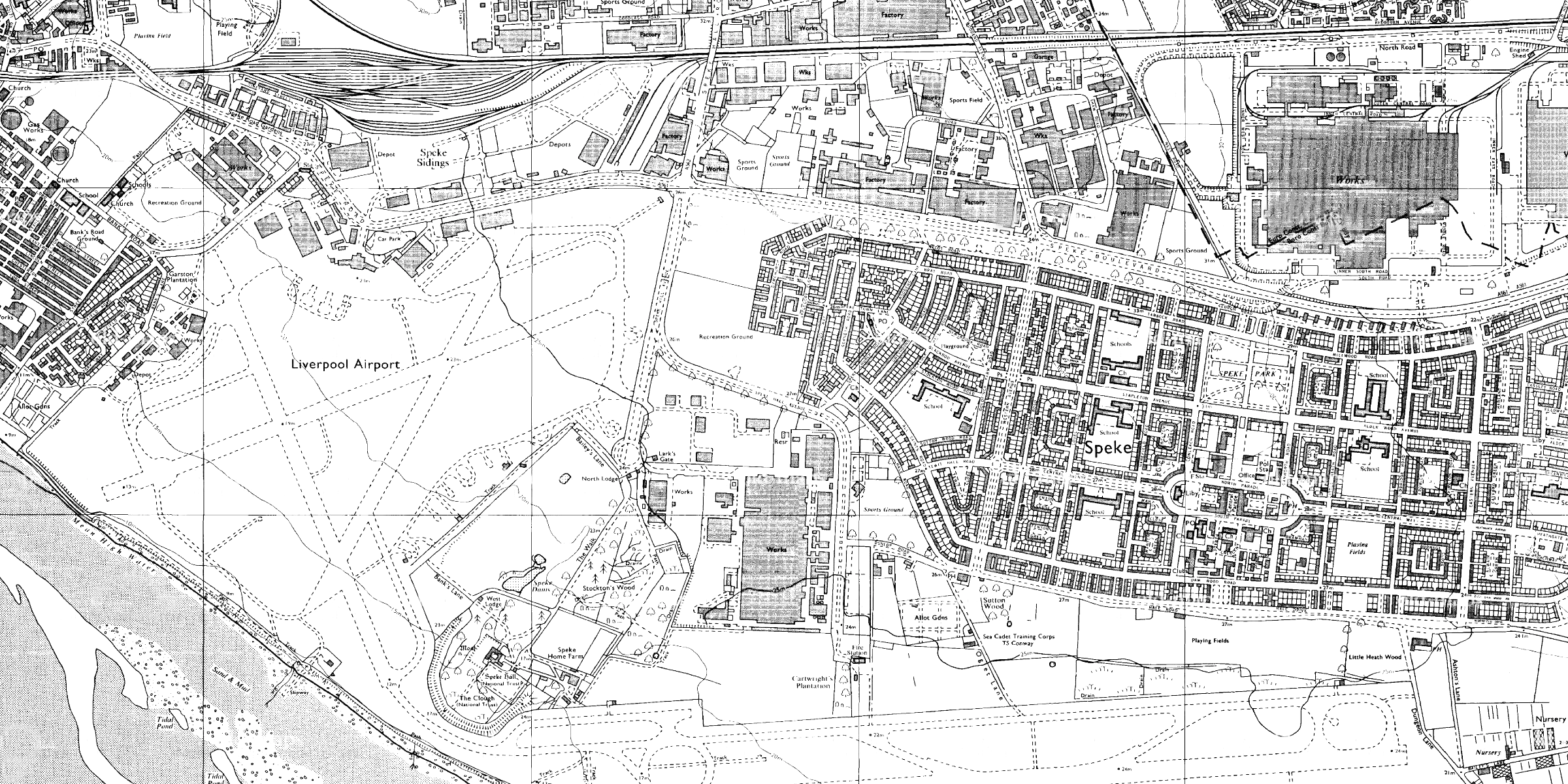

Speke c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

The Landscape

In 1066 Speke formed part of one of Uctred’s manors (along with West Derby and Huyton), and when the Lancashire forest was formed, it became part of the forest fee (Farrer & Brownbill, 1904).

Speke occupies an area in the far south of Liverpool. This is flat land with a long river frontage (at the widest point on the Mersey), and was known for years as some of the best wheat-growing land in the region. Despite its low lying nature and proximity to the river, there are few if any water channels in Speke.

At the turn of the century, Speke was a small village with a scatter of houses, about a mile from the nearest station. The village of Speke itself was surrounded by small villages and hamlets. Oglet lies to the south (Ogelot, Oggelot and Ogelote over the years, especially early on; Oglot and Ogloth also common; Okelot, 1321; Hogolete, 1384 (Farrer & Brownbill, 1904)). Speke Town, Hale Cliff and Hunt’s Cross are the three biggest places of settlement, with a lot of farms dotted around.

‘Hunt’s Cross’ was originally an actual sandstone monument, erected in 1895, but by 1901 was described in the Victoria County History as “a displaced massive square stone socket, lying in a barn, at the crossroads, near the station”.

At the boundary of Speke, Halewood and Hale is an area once known as Conleach. Here, formal challenges were fought between inhabitants of the nearby villages.

Speke Hall

(See main article, Speke Hall and the Speke Estate)

Speke Hall was originally a medieval moated site. The moat survives to this day, although any thoughts of its defensive purpose were long ago lost. For hundreds of years the moat has been no more than decoration to impress visitors. Other sites in this part of Lancashire had similar features, like the building at Old Hutt, and maybe a smaller version at Wright’s Moat.

The site would have fallen within Uctred’s manor, though we can only know for certain that a building stood here since 1314. It passed to an ancestor of the Molyneux, before coming into the hands of the Norris family. William Norris started rebuilding the Hall in 1467, work being completed by Edward Norris in 1589. Only some foundations and kitchen window mullions survive from the sandstone predecessor to the current building (Greaney, 2013, Pye, K.).

Speke remained a small and sparsely inhabited area until the early 20th century. At that point in history Speke’s large neighbour, Liverpool, was becoming hungry for land for housing. Slum clearance was already taking place, and population growth was only adding to housing pressures.

Expansion – the Speke Estate and Industry

In the 20th century Speke was one of several areas of outlying Liverpool which were the focus of post-war reconstruction and expansion (among the others were Knowsley and Skelmersdale). Kirkby, Halewood and Speke were the three largest out-of-town council estates in the country. Unfortunately, there remained a gap between, one the one hand, the houses being built and the residents moving in, and on the other the amenities (shops and leisure) becoming established. This lack of planning led to great problems in the years to follow.

It’s very difficult to separate the history of the Speke housing estate from the industry that grew up from the 1930s onwards. However, it’ll pay to look in detail first into the efforts to re-house people from the city centre.

Building the Speke estate

In the 1930s the population of Speke (the village and its surroundings) was 400. It was to grow to 25,000 by 1950 through the creation of an entire new settlement.

It was hoped that Speke would be an independent town with a large housing stock and its own facilities – sports centre, swimming pool, laundries, shops and a church. The plan was inspired by the popular garden city movement which had created Welham Garden city and inspired the likes of Port Sunlight.

In 1928 Liverpool Corporation bought the land for the Speke estate from the trust managing the lands around Speke Hall (the last inhabitant of the Hall, Adelaide Watt, had died in 1921). In 1932 the area became part of Liverpool, having been part of Whiston rural district, and in 1937 work began on the massive project.

The garden city-plan was executed so strictly that it took little consideration of the natural lie of the land. The gentle topography of the area meant that it had little need to, but other parts of the existing landscape were ignored too. Speke Town, a hamlet, was completed demolished and any remains now lie under the junction of Speke Boulevard and Speke Hall Avenue. The original Speke church was demoted from a central spot to the western edge (Boughton, 2017a).

Living in the Speke estate

The high ambitions for Speke were reflected in the houses that were built. The aim was to encourage a mix of different professions and incomes (Aneurin Bevan had once stated that council estates shouldn’t just be for the poor). Lancelot Keay, architect of Speke, agreed and tried to achieve this aim with a high variety of house types. Over 5000 2-4 bedroom family homes were built, 250 cottage flats for the elderly, 92 single person flats, and 221 2-4 bedroom family flats. Keay also hoped to build all the necessary amenities like a dance hall, a concert hall and a restaurant (Bradbury, 1967).

Fifty per cent were ‘parlour homes’ with unusually high quality and space, for council built residences. Rents were therefore high too, and the unfortunate consequence was a high turnover of residents amongst those who had moved out of low cost city centre areas (Boughton, 2017a).

By 1941 only three shops had been built since people had started moving in in 1939. However, houses were still being built during the Second World War. This was unusual amongst housing estates in Britain. It may have had something to do with the nearby airport, which was taking on its own importance at this time (Boughton, 2017a).

After the Second World War

In the middle of the century it was judged that the houses that had been built before the Second World War were too low density. The developments had used up valuable land which was in even more short supply after 1945 (Bradbury, 1967). The Blitz had left 70,000 people homeless, even aside from the continuing slum clearances.

The Town Development Act of 1952 had encouraged new rural towns like Speke to be built, rather than the redevelopment of town centres, so as to relieve over-population (ibid: 27). Efforts were renewed to develop the housing estate, but with one eye on creating accommodation for a new burst of industry in the area under the auspices of the earlier 1921 Liverpool Corporation Act.

Despite this, even ten years after the houses were built, there were complaints that Speke lacked shops, schools, churches and community centres. Speke was left an “isolated, urban, frontier country” (Speke, 2017). By 1952 The Parade (the planned shopping centre) still had to be built. The author of one article, and a former resident, was 9 or 10 years old before there were any shops to go to.

As with other out-of-town estates, mobile grocery stalls were driven around to supply the residents. An independent Speke would require its own shops and amenities, and so a lack of these left it more vulnerable to isolation than if it had been closer to Liverpool.

Tardy improvements

Despite the problems, and the failure to meet lofty ambitions, some improvements did see the light of day in the 1960s. Although building had seemed to stall once the houses were up, public facilities did eventually appear.

In 1952 a new Speke Library replaced the facility housed in a converted Corporation house. The new building was in a converted smithy at the western end of the Speke estate (Bradbury, 1967). The relentlessly optimistic volume Liverpool Builds (ibid) claimed it had a “rustic charm”, but admitted that it still was not big enough. And so, in 1954, another temporary library was opened in a shop in Alderwood Road (ibid: 121).

Finally, a purpose-build building appeared in 1965 in the form of Speke Central Library. The site had been reserved since before the Second World War, and Bradbury (1967: 116) boasted that it was “the first post-war purpose built library in Liverpool to serve a new area”. That’s quite a string of caveats, but it demonstrated a continued attention being paid to the still-growing community. It was planned that the library would include reference rooms, exhibitions rooms and theatre, with “ample space for all of which has been left at the rear” (ibid).

In the same year as the library, the Austin Rawlinson Swimming Bath and Civic Laundry (named after a West Derby-born Olympic swimmer) opened its doors (Boughton, 2017a). These civic laundries were built across the city in the post-war era, totalling “facilities for almost a thousand women per week”!

The centre of the town, the intended hub of the community, was finally taking shape. The Youth and Community Centre opened in Spetember 1964, having been running for some time already. Some ideas in the original Centre may look dated to modern eyes, such as separate rooms for ‘boys crafts’ and ‘girls crafts’, but its facilities were wide ranging, from a coffee bar to space for netball, badminton and other games (Bradbury, 1967: 94).

The Speke Combined Clinic and Ambulance Station was completed in 1961 on South Parade (ibid: 100). This improved essential response times as ambulances no longer needed to come out from Liverpool. The Station also housed doctors and dentists.

Industry

It was always intended for Speke’s housing and industry to grow hand-in-hand. Industrial estates took advantage of the flat land and growing population from the 1950s onwards. As has been mentioned, post-war development was concentrated on out-of-town areas rather than the inner city.

The 1936 Liverpool Corporation Act allowed the city to buy and sell land for housing. It also let them build factories in order to kick-start development. Speke industrial Estate was built and by 1938 there were 16 factories in the area, and by 1939 there were 28 built or in progress (Boughton, 2017a). The first industries to arrive consisted of motor works, light engineering, food, chemicals and pharmaceuticals. The Bryant and May Matchworks took advantage of its proximity to the Garston timber docks. However, the businesses had moved out of the city along with the residents. These new workplaces were not offering brand new jobs. Rather, they relocated existing ones, and unemployment continued to rise in the Liverpool region (Greaney, 2013).

The slow pace of residential building in Speke disadvantaged these companies too, who complained about slow progress. the Corporation had made them promises to encourage relocation, and they felt let down (Boughton, 2017a).

Speke’s luck truly waned in the 1970s and 80s. The British Leyland plant closed in 1978, and the match factory and the Triumph factory both closed in the 1980s. When Margaret Thatcher’s government set out the Speke Enterprise Zone in 1981 not a single factory opened there (Boughton, 2017b). Decline continued into the early 1990s recession, and Ford’s poor industrial relations added to the woes (Pye, 2009).

Recovery in the 1990s

Speke began to rise out of its low ebb as the 1990s went on. European Union money was spent by the Speke-Garston Development Corporation (a joint venture between the North West Development Agency and the City Council), South Liverpool Housing, and the Liverpool Land Development Company. South Liverpool Housing took over the housing stock from the Liverpool Corporation, and these developments led to investment and long-delayed repairs in the township. In total, this represented £14m in government funding (Boughton, 2017b).

In 1999 Liverpool Vision were set up to coordinate urban regeneration on Merseyside. From 2008 Liverpool Vision funded the redevelopment of Speke’s centre (ibid). Speke Boulevard was styled as an ‘International Gateway’, cementing Speke’s role as an entry point into Liverpool via the airport. Speke was taking advantage of its perfect position as the junction of two motorways, the M56 and M57, algonside links with air, rail and river transport.

Later history

The Speke Estate was an ambitious undertaking. Its architect hoped to build a self-sufficient town full of people with a range of backgrounds and incomes. Industry would go hand-in-hand with the residential growth, and people would live on the doorstep of their workplace.

But the reality was different: house building was too slow for industry’s needs, and the promised facilities were late in coming. By the time they were built, a number of people had already moved on, not intent to wait. All Hallows School was demolished because it had too few students (Speke, 2017).

When the crucial factories closed in the wake of the post-war slump (like Dunlop and Triumph) it only cemented the troubles. It’s been suggested that Lancelot Keay, that ambitious architect, was deluded to think he could build some kind of utopia (Speke, 2017).

Despite setbacks, efforts continued. In the 1980s the tenements which once surrounded open play areas (like the notorious ‘Speke Castle’) were demolished and replaced with modern houses with gardens. In 1998 the Ford plant became a Jaguar factory. The factory was modernised from a production line to a “total quality management” system using modern manufacturing processes (Pye, 2009). Following the transfer of housing to South Liverpool Housing there’s been a renewed effort to build the original vision of a mixed community (Boughton, 2017b). Measures have been taken like enforcing a minimum proportion of affordable housing in new developments.

Time will tell whether the new energy put into Speke pays dividends.

Transport – the Airport

1928: Airport site bought from Miss Adelaide Watt

1930-3: airport construction

1933: Speke Airport opened. By WWII it was the second busiest in the UK. Air Force kept control after war meaning it lost out to Manchester in 1950s.

1935-40: Edward Bloomfield’s building built

Became RAF Speke until 1961.(Book)

References

Farrer, W., & Brownbill, J., 1907, The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster, vol III

Speke, Tom, 2017, Growing up on the Speke Estate, Liverpool: a personal perspective, https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2017/08/01/speke_a_personal_perspective/, accessed 9th July 2019

Boughton, J. 2017a, The Speke Estate, Liverpool: a ‘satellite town…planned to accommodate all classes of the community’, https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2017/04/25/the-speke-estate-liverpool-i/, accessed 10th July 2019

- https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2017/05/02/the-speke-estate-liverpool-ii/, accessed 10th July 2019.

Greaney, M., 2013, Liverpool: a landscape history, History Press, Stroud

Bradbury, R., 1967, Liverpool Builds, City and County Borough of Liverpool, Liverpool