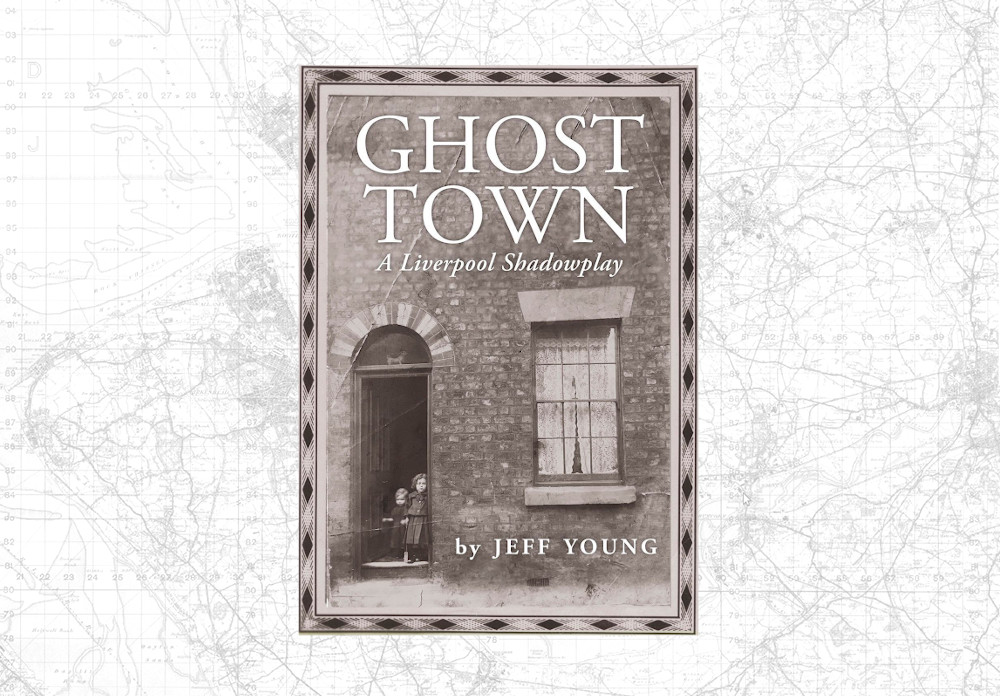

This book is a memoir, and many of those have been published over the years (and a couple reviewed on this very site). Like some of those other memoirs, it is a series of reminiscences on family and place. But it’s a slightly different beast to the other memoirs. It’s main selling point is that it comes from the pen of Jeff Young, a writer with TV and theatre credits to his name, such as the play Bright Phoenix.

The book has a dream-like quality, with reality, dream and (science) fiction becoming intertwined and difficult to separate. The young Jeff walks unharmed through gangs of older boys you’re sure are going to pounce. His solitariness, the muse for his writing, may be a shield.

Strangeness and time

The book isn’t chronological, as such, and neither are the wonderful photographs that separate each chapter. We see Jeff and a friend wandering Everton in recent years, a suburb which has largely disappeared since their boyhoods. Here they experience something of a timeslip. A revenant from a previous era floats through the scene and heads towards town. We’re following (maybe literally) De Quincy’s travels through the city, but through the eyes of a Scouser. These are geographic travels around town that summon old things, memories and people. This isn’t the last time slip; neither is it the last time Jeff will look up from his reverie and find the city emptier – cleared, demolished – than he remembers it.

Dreams invade the narrative, and shape it. Russian tanks are rolling into Prague. Or are they only doing this in dream? Remembrances of coinciding events prove false – the moments occured years apart, but are forever significantly linked somehow in Young’s mind. He distinctly remembers seeing Daleks: Invasion Earth (1966) at the Grosvenor cinema… which closed in 1963. A dramatic incident on matchday years before, involving a police horse, is burned indelibly on his mind… except he wasn’t there; he’s absorbed a tale his mother must have told to a neighbour. The important thing to state is that he knows all this, and it’s part of the story.

Science Fiction writer China Mieville gets two mentions, with one for his City and the City. Young doesn’t mention the fact that the TV version was filmed in Liverpool, but at least for me this is a story through which reality and fiction become blurred.

Landscape and memory

At some point in Young’s life the family move (are moved?) from the inner city to Maghull, and there’s a whole new landscape to explore. The boy takes to it naturally, and the terraces of yore are replaced with fields, jiggers with ditches and the canal.

If his TV work (including EastEnders and Doctors) brings creativity to coverage of the ‘everyday’, then this talent is brought to bear when recalling memories of the 1950s and 60s in Liverpool and then Maghull. I was reminded by the tone of the thing of Ronnie Hughes of A Sense of Place, especially of Ronnie’s own ‘checking up’ on his home town. The tone conjours feelings of nostalgia and warmth towards its subject, without the cloying ‘we-wuz-happy’ of many memoirs.

As he grows up, he haunts new landscapes, like Mathew Street and its various popular and mythical inhabitants. Liverpool in the 1970s experienced a creative boom, giving life to Eric’s and Ken Campbell’s Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun. The landscape is often of dreams and whimsy – important whimsy – populated by Ken Campbell, Bill Drummond and more. It’s a timely reminder that Liverpool’s culture didn’t die with Merseybeat.

Historic Architecture

The thing that surprised me is just how closely Jeff Young’s life and work has intertwined with the historic Liverpool landscape. In Bright Phoenix kids break into the old abandoned Futurist cinema, breathing new, if temporary life into something that meant a lot to them and their parents. Young has an ‘architectural hero’ in the form of Peter Ellis. His mum sneaks into Oriel Chambers with him (or rather he sneaks in with her), and he has moments trying to understand its strange (and, at it’s opening, unappreciated) beauty.

There’s an example of his insight into architecture and change when it comes to Rowse’s tunnel ventilation building. He notes it looks more futuristic, with its streamlined statue of ‘Speed, the Modern Mercury’ than anything that came after, like the car parks, the (late) flyovers and the footpaths in the sky. And he’s got a good point. He rues the possibility that the Tipping Buckets fountain in Beetham Plaza might be relocated, replaced with a hotel for visitors at the very moment a reason to visit the plaza is removed.

It turns out that Alfred Shennan, architect of many Liverpool cinemas (including the Grosvenor) was once his mum’s boss. As Young himself says, the map of Liverpool is in his blood – “This place is myself” (p133). It’s as much an admission as a realisation. So when a little of that landscape is destroyed, it saddens him. Referring to the replacement of the Futurist with a Lidl, he points out:

“No one will ever again say that last night they went down Lime Street, unless in a story about buying a bumper pack of toilet rolls.”

And this just about sums up how a playwright can articulate something about changing Liverpool better than most of us. (And maybe such stories will be all too common in 2020!)

The book

This is a book which recalls a childhood and adolescence that may not have happened quite this way. But that just means that it evokes the nature of memories so much the better. There’s an admission all the way through that any of the recollections could be subject to change.

True, there are people in desperate circumstances, like the market scenes where the items for sale are as in deepened straits as the customers. But this balance lends further realism, a way of witnessing dark times through the eyess of a young person who knows – expects – nothing more. A boy who wants nothing more than “whatever we have” to never end. Ignorance is bliss, even with 20:20 hindsight.

The book unexpectedly provides great insight into what it’s like to witness the changing of a city. Sometimes it’s gradual, changing with the viewer, and sometimes it’s sudden, as when he returns after an absence to an unrecognisable landscape. He’s expanding outside what we might expect of him, and he proves himelf up to the task, as we all are.

The book itself is a beautiful object, a perfect size for long reading sessions – and I nearly absorbed the whole lot in a couple of hours! It’s beautifully produced, let down only by the low resolution maps (I know!) on the inside covers. In some ways it’s similar in feel to Our Liverpool by J.P. Dudgeon, but more positive, perhaps more honest, but capturing more truth of life because of it. It balances the hindsight of adulthood with the genuine memories of a child.

Many years ago, Young swore to leave Liverpool behind forever. But times, and people, change, and this cements his return.

Get the book

Disclosure: I must give my thanks to Little Toller Books for sending me a copy of this book for review.

Ghost Town by Jeff Young was published in 2020 by Little Toller Books. You can get it from the Hive network of independent bookshops (affiliate link) or direct from Little Toller’s website.

Images

All photographs are released under Creative Commons licenses. Follow the links to find out more details.

Views of the city from Everton Park by Radarsmum67, via Flickr.

Leeds & Liverpool Canal Towards the M58 Bridge by Ian S via Geograph.

Liverpool: detail of Queensway Tunnel building by Chris Downer via Geograph.