Woolton is a very old centre of settlement in the north west. Situated in the southern part of the Liverpool today, historically it consisted of two distinct areas – Much Woolton and Little Woolton.

The entrance to the village of Woolton itself would generally have been via Out Lane, past the Woolton village cross and into the town gardens. In the medieval period this route would have taken you through small fields of mixed cultivation, with ponds dotting the landscape. The ‘great meadow’ had recently been reclaimed from the waste, and lay to the south east of the village centre.

Source: like many the townships in Liverpool, Woolton has an excellent history book written by members of the local society. These books are well researched and produced, but can be hard to get hold of.

In the case of Woolton, the book is John Lally and Janet Gnosspelius’s History of Much Woolton, published in 1975 by the Woolton Society (and reprinted in 2012). Much of the detail in this article can be found in that book, but because I concentrate on landscape history there is so much more than this to be found in its pages. If you happen to see a copy come up for sale, I urge anyone interested in Woolton’s history to pick it up.

Book

Hard to get hold of these days, Lally & Gnosspelius’s book is a professional and detailed history of Woolton and the local area. Apparantly the precursor to a bigger study, though I’ve not found that follow-up.

Website

The Woolton Society is active in helping preserve the historic character of the village and local area, and its website has details of their talks and other events.

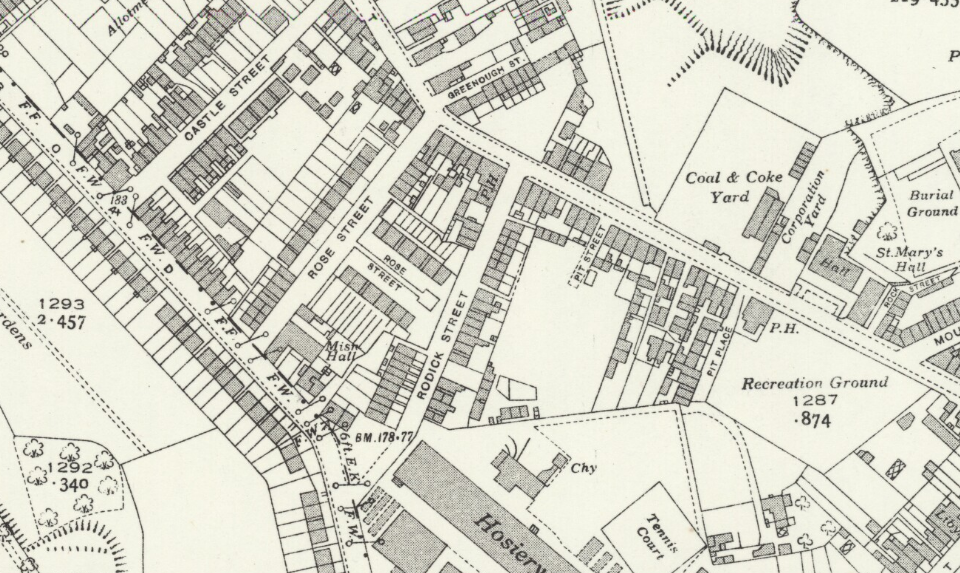

Woolton c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

Little Woolton and Much Woolton

Woolton has the unique character in Liverpool of being split into ‘Much’ and ‘Little’ parts. Often this place name split suggests that one part is larger than the other, or even that the ‘Much’ part is on higher ground. It’s not known how Woolton gained its two names, except that Little Woolton was already a separate manor at the time of Domesday. Little Woolton was in the possession of the Stanlaw Monks in the 13th Century. Woolton village itself is in Much Woolton, and this may have been enough to gain it the name.

The road through Little Woolton leads to Liverpool via Childwall, Wavertree and Toxteth, while another runs south east to Halewood.

Field names survived until relatively recently. Dam Meadows, Dam Croft and Naylor’s Bridge all suggest the area was criss-crossed by streams which could be harnessed for industry and agriculture. Other evocative field names include Monk’s Meadow, Causeway Field, Hemp Meadow, Tanhouse Meadow, Shadows, Winamoor, and Creacre. Coxhead Farm has a name derived from Cock Shed.

Natural landscape

Woolton sits on the southern slopes of a ridge running North-West to South-East across the district. Glaciers split the ridge into two hills, and the geology is boulder clay underlying wind-blown sand, like much of Liverpool. The ridge position meant that the land here was drier than in the surrounding lowlands, and Woolton grew up on the northern side, out of the way of the prevailing winds from the south west.

The wetter land was not drained, and therefore was not used for agriculture, until the Middle Ages. There simply wasn’t the population pressure to develop this land until then.

Prehistory in Woolton

Little is known about the very early (pre)history of Woolton. It lacks the prehistoric remains like the Calderstones or Robin Hood’s stone nearby, but it does have a suspected Iron Age hill fort in the form of Camp Hill. A Victorian villa built on the site of the hill fort, on School Lane, means that very little is likely to be found out about the site through excavation.

At the time Domesday Book was compiled there was farmland enough to support eight or nine households. The value of the manor was low compared to nearby townships like Childwall, which was a parish in its own right.

In about the year 1180, John, constable of Chester, granted his lands at Woolton to the Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Knights of St John. These knights were sworn to protect pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land, and used grants like this to raise money (via rents). They were probably not given all of Much Woolton, but had acquired it a few years later, and also had part of Little Woolton by about 1292.

It’s been suggested by Lally and Gnosspelius (1975: 9) that the Knights may have established a ‘camera’ – a centre of administration – in Woolton. This would have helped administer all the Hospitallers’ lands in south Lancashire, but whether it would have taken the form of a physical building (as survives in part in Stidd north of the Ribble) or a more abstract ‘centre’ is open to question.

The village

A survey of 1338 mentions a water mill in the village. This might have been around the site of Peck Mill house. Field names around here suggest dams on Childwall Brook (Lally & Gnosspelius, 1975: 10).

Like a lot of England, Woolton experienced hardship around the time of the Plague in the 14th century. There was also a series of bad harvests and outbreaks of ‘murrain’ (a general term for cattle and sheep diseases).

Field names from the 12th to the 14th century point to a process of bringing new land into cultivation.

- Ofnames (1187) shows formerly marginal land newly cultivated.

- Hadbote (c.1323) consists of short strips (‘butts’) of land taken out of heather-covered waste.

- Merchedoles (1350) are doles in marshy or watery (and hence of lower agricultural potential) land (Lally & Gnosspelius, 1975: 12).

The 1332 poll tax return for ‘Wolveton Magna’ shows 10 men liable for paying this tax, while ‘Wolveton Parva’ had 7.

The medieval diet was generally limited to what could be grown locally. Oats, beans, peas, porridge and eggs were supplemented on rare occasions by meat.

There were two windmills standing in 1613. Only one had survived by 1900. This stood on Church Road to the north of St Peter’s, high up on the hill above Woolton village.

Early modern Woolton

In 1608 a rental list tells us that there were 29 households and a handful of non-dwelling plots of land in the township, along with a windmill. This translates to a population of about 130. In 1658 this had risen to 39 households – about 175 people in all likelihood, plus freeholder families.

At the start of the century Woolton Cross was considered to be marking the northern end of the village, but in less than 50 years the built-up area was stretching north along Woolton Street.

The oldest known map of Woolton was made in 1613. It shows 8 town houses and areas of common land that were soon to be divided up and enclosed: Brown Hill (Woolton Hill), Birch Hill (Woolton Woods) and the waste ‘to get marle on’. (Marl is a clay-based fertiliser which was dug from pits to be spread over fields. These marl pits were likely near the present Recreation Ground and (of course!) Pit Street.)

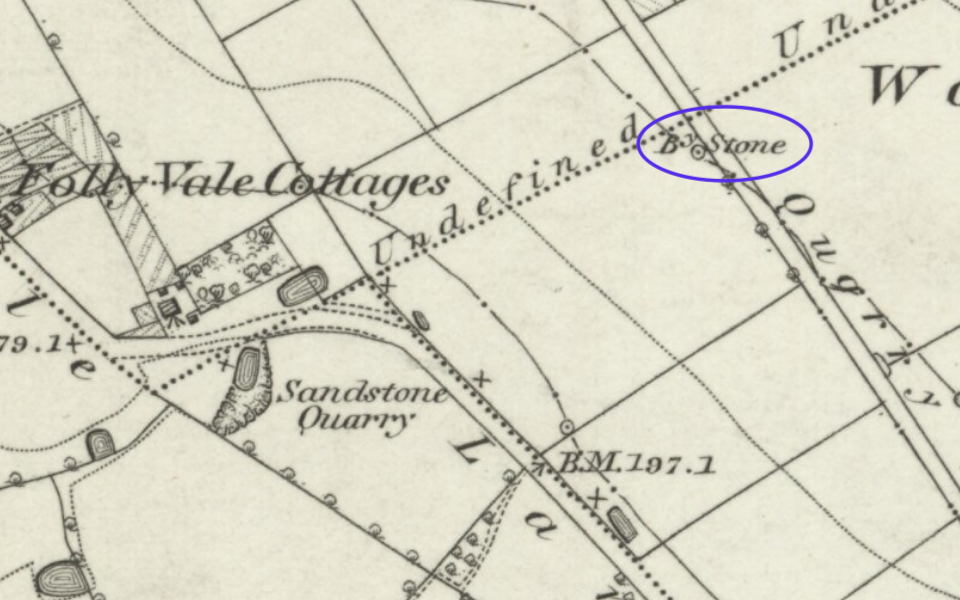

A 1658 description of the township boundary was as follows: From Out Lane to Halewood Road leading to Gateacre, then up to the brow of the hill where there are merestones near a marl pit on the edge of Allerton township.

From here, at the north end of Vale Road, the boundary follows an old watercourse across Menlove Avenue (as it now is), east of Elm Cottage. It passed a ‘nook of a close’ called Pendleton’s to the boundary of Speke, to Hillfoot Road and Hillfoot Avenue, past Mackett’s House and back to Out Lane.

It’s also known that by this time one of the township’s two post mills had fallen into disrepair.

Woolton Tunnels

There are interesting rumours about tunnels under Woolton. It’s said that they run from Woolton Hall in three directions:

- down Watergate Lane;

- towards a house in Woolton Street;

- towards Ashon Square.

No one known what these tunnels might be for, though escape routes for Catholic priests after the Reformation have been proposed.

Lally and Gnosspelius (1975: 24) acknowledge that passages like these exist, but how closely they match the rumoured routes is not known, and neither is their date.

Enclosure of Woolton

In the same year that the boundaries of Woolton were set down, a new plan was made to enclose the land and consolidate holdings.

The Earl of Derby, as the greatest land owner in the area, received 40 acres; 80 acres went to freeholders and charterers (the latter seemingly meaning something similar to the former, but specific to Cheshire ). Each freeholder and charterer was given an amount in proportion to their land holdings in Much Woolton.

Interestingly, this plan was never put into action. Lally and Gnosspelius (1975: 20) put this down the the Civil War interrupting the process.

Quarries

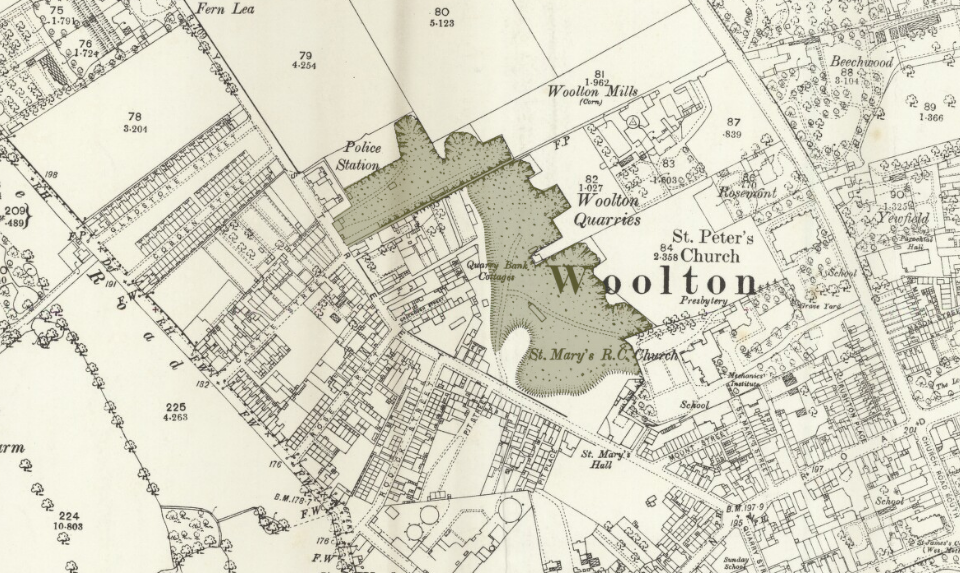

Like many parts of Liverpool (such as West Derby [LINK]), Woolton had quarries. These produced the desirable red sandstone used for all sorts of buildings, from cottages to merchant palaces like those built on the lands of Allerton Hall (such as Allerton Priory, Allerton Tower and Springwood). One Woolton quarry supplied the stone for the Anglican Cathedral – probably one of the last customers it had before it closed. The peak of quarry use was in 19th century.

Quarry Street commemorates the presence of the quarries, with an old (and very large) quarry being at the village end, and a newer quarry at the north end. Another quarry was on Woolton Hill road, near Reynolds Park.

Childwall and Woolton Waste Lands Inclosure Act (1805)

Enclosure acts needed the consent of those who held land in the area. The Gascoyne and Ashton families held enough land in Woolton to see the 1805 Act through.

New roads were laid out as part of the scheme: School Lane, Allerton Road, Church Road and Quarry Street (the latter formerly known as Delph Lane). These streets, like many during enclosure, would probably have been developed from pre-existing lanes.

Gascoyne and Ashton got the lion’s share of the redistributed land, but everyone who had a parcel had to build fences around it. This aspect of the law led to a lot of new small stone walls, some of which still survive.

Much has been written about how enclosure forced people off the land, resulting in poverty and job losses. In Woolton, James Rose’s industry and wealth grew up on the back of developments enabled by enclosure (his quarries were in great demand, for example), and so local work and jobs increased.

The people of Woolton

As the Industrial Revolution took hold, work for labourers came from the docks and railways in Garston. Navvies, stonemasons, quarrymen and carpenters were all needed. The large Woolton houses springing up would have needed builders, decorators and carpenters of their own, as well as maintenance staff.

By the turn of the 20th century, houses were being built for this workforce. The houses on Ashton Square are labourers cottages, and Castle Street had labourers’ cottages too. What stands out is the wide variety of fortunes that inhabited Woolton. There were the very richest industrialists of the Victorian era and the poorest and least healthy workers sharing the village. It was a matter of a few minutes walk to travel from back-to-backs to mansions.

Many of the smallest dwellings have been cleared now. Just under 450 people occupied 58 houses on Rose Street, while a similar number were in 88 houses on Rodick. This overcrowding was a problem that could only be solved by the wrecking ball. The vast majority of the houses on these streets today are mid-20th century or later.

Today, Woolton is a suburb of Liverpool which has retained much of its historic character. Woolton village was never a place which stopped developing. It had been a small rural village for centuries, but during the Victorian period saw the influx of everyone from industrialists to labourers. Today it is still evolving, with new houses being built close to its centre, but it still attracts people to its parks and its historic cinema.

Woolton Street and Woolton Green

Woolton Street runs close to Woolton Hall. Its odd shape is the result of a change made by Richard Molyneux (not dissimilar to that made in West Derby, on Queens Drive). The street once ran south to Ashton Square, but before the publication of the Yates & Perry map in 1768 it had been diverted away from the Hall.

Interestingly, when Lally and Gnosspelius redrew Woolton Street along its supposed original route, it marked out an area which they suggest could have been Woolton Green, between Woolton Street and Speke Road (1975: 29).

Their argument is supported by the way buildings are oriented here. Two buildings have their gable-ends facing the ‘Green’, from outside it. Woolton Green was the name of a local fair, surviving until the 1870s.

Further Reading

Lally, John E., & Gnosspelius, Janet B., 1975, History of Much Woolton, The Woolton Society, Liverpool (Interim study in celebration of the European Architectural Heritage Year 1975

Woolton Mansions Walk http://www.bbc.co.uk/liverpool/content/articles/2006/12/15/woolton_mansion_walk_feature.shtml (accessed 25th May 2020)

Woolton, South East Liverpool https://neam.co.uk/liverpool/woolton.html (accessed 25th May 2020)