The history of Hale is closely related to its position on the River Mersey, and the crossing to Cheshire. Ram’s Brook has long formed the north boundary of the township. The landscape is flat, with Lombardy poplars in plantations and farms. Henry II placed part of the township within the hunting forest, although it was disafforested again by Henry III.

Hale was one of 6 berewicks of the manor of West Derby in 1066. The name comes from ‘halh’, Old English for nook or haugh (a low lying and flat piece of land in the valley of a river). The village was also known as Halis in Henry III’s reign and Hales later on.

Hale is now part of Halton in Cheshire, but is included on this website as it covers some of the important parts of Liverpool’s history. To the north is Ciss Green, and to the west lies Dungeon (and Dungeon Banks in the Mersey), where saltworks could once be found. This part of the river front was proposed for embanking the river in 1817, but nothing came of the project.

Book

This well-produced booklet covers all sorts of topics, so if you’re interested in reading further about the important families of Hale, this is the book for you.

Website

Hale village is lucky enough to have enthusiastic residents who have compiled this collection of historical information. There’s more than just history here, though, so a perfect starting point.

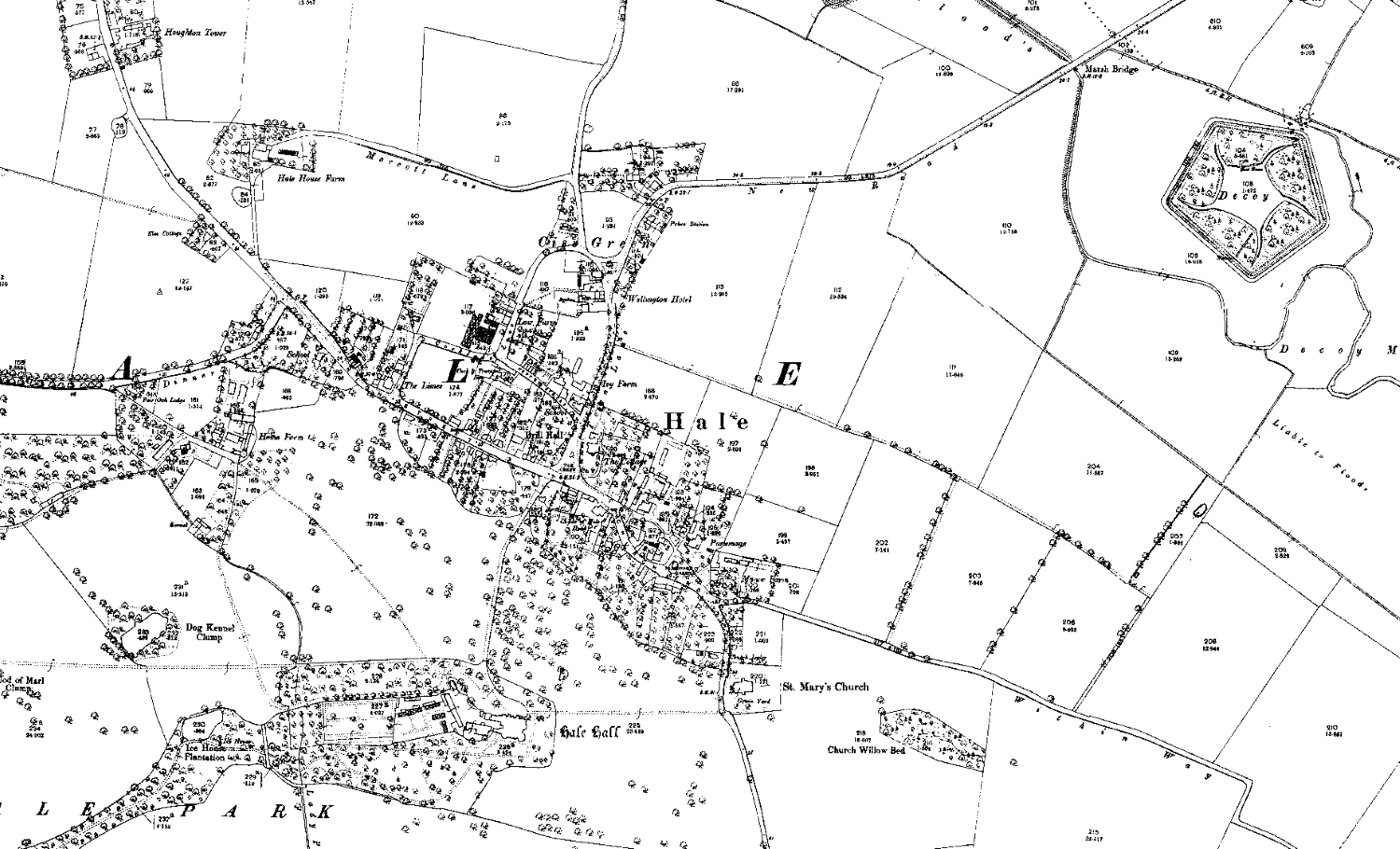

Hale c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

History of the Manor of Hale

We know William the Conqueror often granted portions of his new lands to his allies, but the king kept Hale for himself. Only in 1203 did a monarch pass on the lands: John gave Hale to Richard de Walton.

Henry II brought part of Hale into the royal hunting forest (Toxteth being perhaps the most famous part) in the 12th century. However, by Henry III’s time on the throne the area was no longer subject to forest law.

The history of Hale village

Medieval villages had an often predictable pattern. A high street down the centre had houses, a pub or two, and businesses fronting onto it. The church and manor were nearby, the entrances to them usually in the centre of the village.

Fields lay behind and beyond the houses, and butted on to a ‘back lane’. Paths led between some of the fields, taking people from the high street to the back lane. Often the back lane retains its name, but if it doesn’t then old maps can show evidence of the name change. An example is Eaton Road in West Derby, which is marked on some old maps as ‘Back Lane’.

A ‘back lane’ existed throughout the history of Hale right up until the 19th century, on the south side of the High Street behind the houses there. The back lane gave access to fields where Hale Park is now. It started at the driveway between the Childe’s House and the row of cottages next door. Mike Royden notes that it has left a “distinct ground impression” here. The lane then turned across the Park parallel to the High Street, and passed Home Farm. Today, the back lane here is the access road to the Farm itself. At its other end, the back lane came out onto Hale Road.

Fields and the back lane

The Enclosure map of 1803 clearly shows this back lane, as well as two paths leading back to the High Street. One went from Cocklade Lane to the back lane, while the other became the entrance to Hale Park.

Cottages once lined the two paths, as well as the back lane itself, at the time of the survey for the Enclosure map. Having dwellings on these ‘minor’ roads is an odd layout, and makes Hale village a little unique. Mike Royden suggests that this portion of the back lane might once have been the high street itself, with the current High Street being a later addition to the landscape.

When John Ireland-Blackburne, the lord of the manor, renovated Hale Hall in the 19th century, he demolished these cottages and landscaped the whole area. It was then that the back lane and the paths between it and the hight street saw alterations.

Fields in Hale

Dr. Rob Philpott has looked at Ireland-Blackburne’s estate map of 1837. That map shows narrow field strips labelled ‘Townfield’ between Within Way and the road to Widnes. There are also documentary references to a South Townfield. Aerial photography has revealed remains of field strips in a field between Church Willow Bed and the dog-leg in Within Way. These are all remains of strip farming that would have been Hale’s primary economic activity up to the Industrial Revolution.

Finally, a field named Rabbit Hey suggests the presence of a rabbit warren. People caught rabbits for meat and fur, probably around the 16th century. They were more common on areas away from ploughed fields, so either people abandoned the warren before they laid out the strip fields, or built after the fields themselves became disused. There are very few distinguishing features of the warren to say any more about it.

Other historic features in Hale

The history of Hale Point contains stories that reveal how dangerous this point on the Mersey can be. It’s shifting sands meant it could turn from a ford into a dangerous channel from tide to tide, and many lost their lives or ran aground here. You can read about Hale Ford and Hale Lighthouse, which take in both aspects of this part of Liverpool, elsewhere on this site.

Other features of the village are:

- the war memorial (1920), paid for by the Ireland-Blackburnes;

- the village hall (1974), built on the site of the old Drill Hall;

- a salt works (19th century) at Dungeon (the industry relocated from the central Salthouse Docks), and

- a cross on the main street, mentioned in a charter of 1387.

- William Part School: built in 1739, and extended in 1875 at the expense of the master. The building is now a dwelling and (in its extension) a youth club.

Hayes (1991: 61) gives this quote from ‘the first half of the last century’ (i.e. 1800 – 1850, and note that this book is a reprint of a 1910 original):

“The village of Hale is one of the neatest and most rural in all this part of Lancashire. Being at a distance from any road, and destitute of any manufactury, it is sequestered and peaceful. The cottages are healthy, thatched and whitewashed, while the handsome modern villa of the clergyman, built in 1824, and the venerable mansion formerly the parsonage house, though at present nothing more than a farm house, adorn the village green. The church is kept with much neatness, and is a charming retreat from the noise and bustle of the world.”

from Stories and Tales of Old Merseyside

The history of Hale Hall

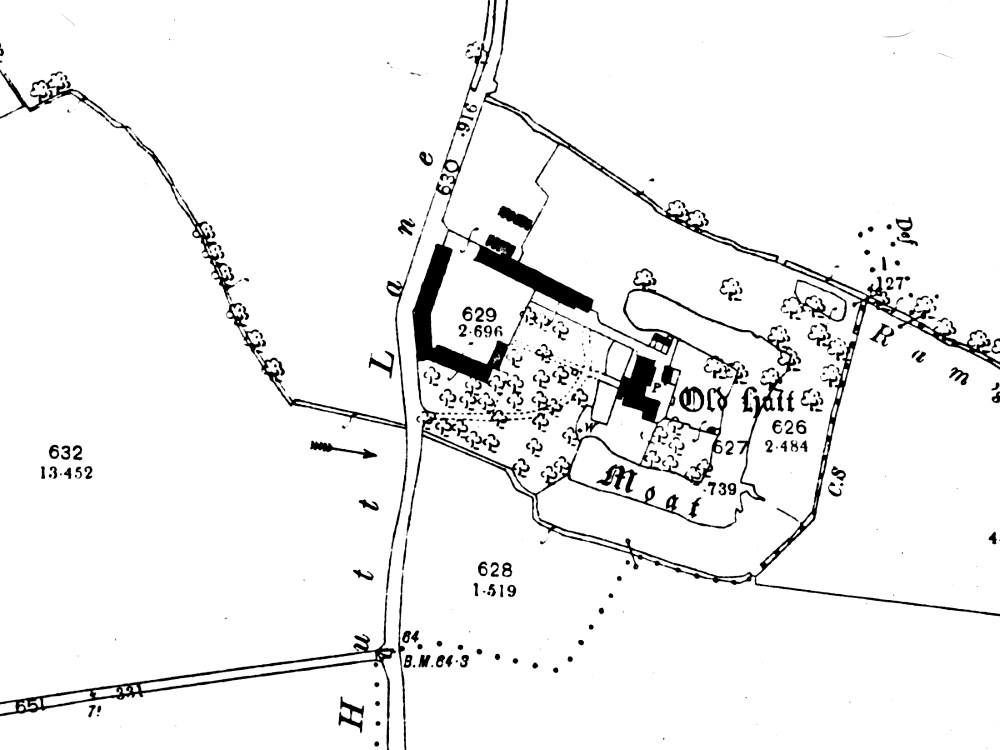

The original seat of the lord of Hale was the Hutte. Yates’s map of 1786 shows the moated house, but had probably been in existence for centuries already.

The Hutte had deteriorated badly by the early 17th century, and so the Blackburn-Irelands laid the foundations of Hale Hall as a replacement between 1617 and 1626. In 1674 Sir Gilbert Ireland-Blackburne completed some alterations to the Hall before he himself moved in.

Hale Hall and Park

Hale Hall, begun by Sir Gilbert Ireland, replaced the Hutte in the 17th century. John Ireland added an impressive south front in 1806 and a lodge in 1876. You can read more about the history of Hale Hall elsewhere on this site.

Hale Park was designed and laid out following principles put forward by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. Landscapes ‘improved’ in this way were often unsentimental, and parts of Hale itself were demolished to make way for changes and extensions on the north side of the Park. At the same time oaks and limes were planted, and more new trees added to celebrate the the coming of age of family members.

Ice House

Hale Hall’s first ice house was originally near the main building, but the one seen today is to the river bank. The construction date is not known exactly, but it’s likely to be the period between the 17th and 19th centuries. This period saw a fashion for ice houses across the country. It could easily have been part of the 1806 renovations of Hale Hall, especially as it is made of bricks like those used in the Hall’s extension.

It’s purpose was to store ice to help keep meat fresh in the days before electric refrigeration, and so many features of the building contribute to keeping it insulated.

It is an underground egg-shaped chamber, except for a portion above the surface. Soil and bracken cover this portion to keep the temperature down. The ice house is close to the river which was a source of winter ice, and the interior, lined with bricks and then with straw, keeps in the cold. A partly filled pool nearby was another source of ice.

The Childe Of Hale and his Cottage, Church Road

John Middleton could claim to be the greatest celebrity to come from Hale. He is reputed to measure 9’3″ (2.8 metres) tall before his 20th birthday, and stories both true and mythical surround the man.

Born in 1578, legend tells that he wished to be tall, and so drew a huge outline on the sand in the beach and lay down in it. When he awoke he had taken on the giant proportions that made him famous. Another story says he wished to be ‘great’, and no sooner had he made the wish than it came true – he was to be ‘great’ in size as well as in life.

The name ‘Childe’ not only refers ironically to his height, but also his reported ‘simple’ nature and gentle personality. Gilbert of Ireland took him to London to see King James, and to fight the monarch’s own wrestler (he reportedly won). Gilbert later hired him as a bodyguard (and no doubt to show him off as a curiosity).

The life of the Childe

There is no record of a marriage, but he lived in the building known as the Childe of Hale Cottage on Church Road. There is a story that his family removed the horizontal roof beams to deal with his height. Another tall tale suggests that he slept each night with both feet sticking out of the two small windows which open onto the street!

Gilbert Ireland was a student of Brasenose College, Oxford, and to this day a portrait of the Childe of Hale hangs in Brasenose (and another in Speke Hall). He is a symbol of the Brasenose College Boat Club.

Middleton died on August 23rd, 1623, and his grave is in St Mary’s Churchyard. It’s an impressive tomb: a massive stone slab, surrounded by iron railings and engraved with these words:

Here lyeth the bodie of John Middleton the Childe Nine feet three Borne 1578 Dyede 1623.

Courts and fairs

As a manor, Hale had rights to hold a court and fairs. The Magna Curia de Hale was a document which dictated the terms of the Great Court, held annually on the Wednesday before St Andrew’s Day. The court-leet (where groups of villagers shared responsibility for alleged crimes) took place on Michaelmas Day. If the accused did not appear at court then a fine could be given to the entire group. The Court Baron (dealing with matters relating to the lord and manor and his tenants) happened on the same day. The town hall played host to these two courts, but when this was demolished in the early 19th century the courts moved to the Child of Hale Inn. Both Sir Molyneux and Lord Stanley received fines in their absence at one time or another by Hale courts.

The court events were also times to choose constables, a coroner, water bailiffs (who took anchorage fees in the manor), burleymen (charged with testing boundary fences and acting as trespass officers), ale tasters (quality control!) and house and fire lookers (so important in a largely thatched community).

In the early 19th century a fair for toys and other wares took place on 19th November. On the day of the fair the freemen of the manor, chosen by the manor court, appointed a mayor. King John granted the rights for Richard of Meath, then lord, to hold a market and fair in 1304. The village revived the custom in May 1967.

St Mary’s Church

Hale’s main church replaced a chapel built in 1088. It has a square churchyard which contains the graves of two of Hale’s notable residents: the Childe of Hale and John Ireland (dating from 1462).

The tower is original (14th century) but updates and modifications to the body of the church mean it is much younger. In 1308 Adam Ireland built a new aisle and restored the stained glass windows. The church once had a pinnacle, but this is no longer there.

There are two phases of extension to the churchyard, and stone plaques show when this happened. One is to the rear of the church, the other near the yew trees on the Manor House side.

Sadly, on 19th October 1977 a fire gutted the structure. The fire destroyed much of the interior furniture and decorations, and so donated items later replaced the lost parts. Builders reinstated the roof at a lower level; the original roofline is visible in marks on the tower. During renovations, builders found the remains of a narrower wooden church.

Sources

https://www.halevillageonline.co.uk/ (accessed 10th Jan 2018)

http://www.thefriendsofpickeringspasture.org.uk/hale-duck-decoy.html (accessed 15th Jan 2018)

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/mikeroyden/liverpool/hale/hale.pdf (accessed 16th Jan 2018)

Hatton, P.B., 1978, The History of Hale, P.B. Hatton, Hale