Garston lies on the banks of the Mersey, to the south of Liverpool city centre, and Toxteth. The history of Garston is closely related to the docks and railway, and grew into an important industrial suburb of Liverpool. The Otterspool separates Garston from Toxteth. Two other brooks once flowed through the area, one of which flowed through the village and into the river. By the early 20th century coastal erosion was already a known threat to the area, with 15 yards being lost in 25 years. Aigburth and Grassendale constitute the spread of the suburb from its original centre, but as little as 100 years ago fields for grazing were to be found between the houses.

Origins of the name: There are two possibilities as to the origins of the place-name ‘Garston’. The first is a route through Old English, to mean spear, dart, javelin, shaft arrow, weapon, and also spear in Norwegian, Icelandic and Old Norse. Alternatively, the Old English ‘geard’, meaning garden, may be the root. In this sense, the garden would have been where livestock were grazed.

So, Garston may once have been a place where cattle or sheep were held, or alternatively a place where spears or the like were made. The uncertainty, heightened by the two possible language origins, was not uncommon in areas like Merseyside where Norse and the English mingled.

Book

One of the excellent range of books from the Images of England range, this book couples photographs from Garston with captions, retelling the scenes and how the history fits the bigger picture.

Website

Garston has its own local history society, and their website contains a huge number of pages covering photos, genealogy and their own publications.

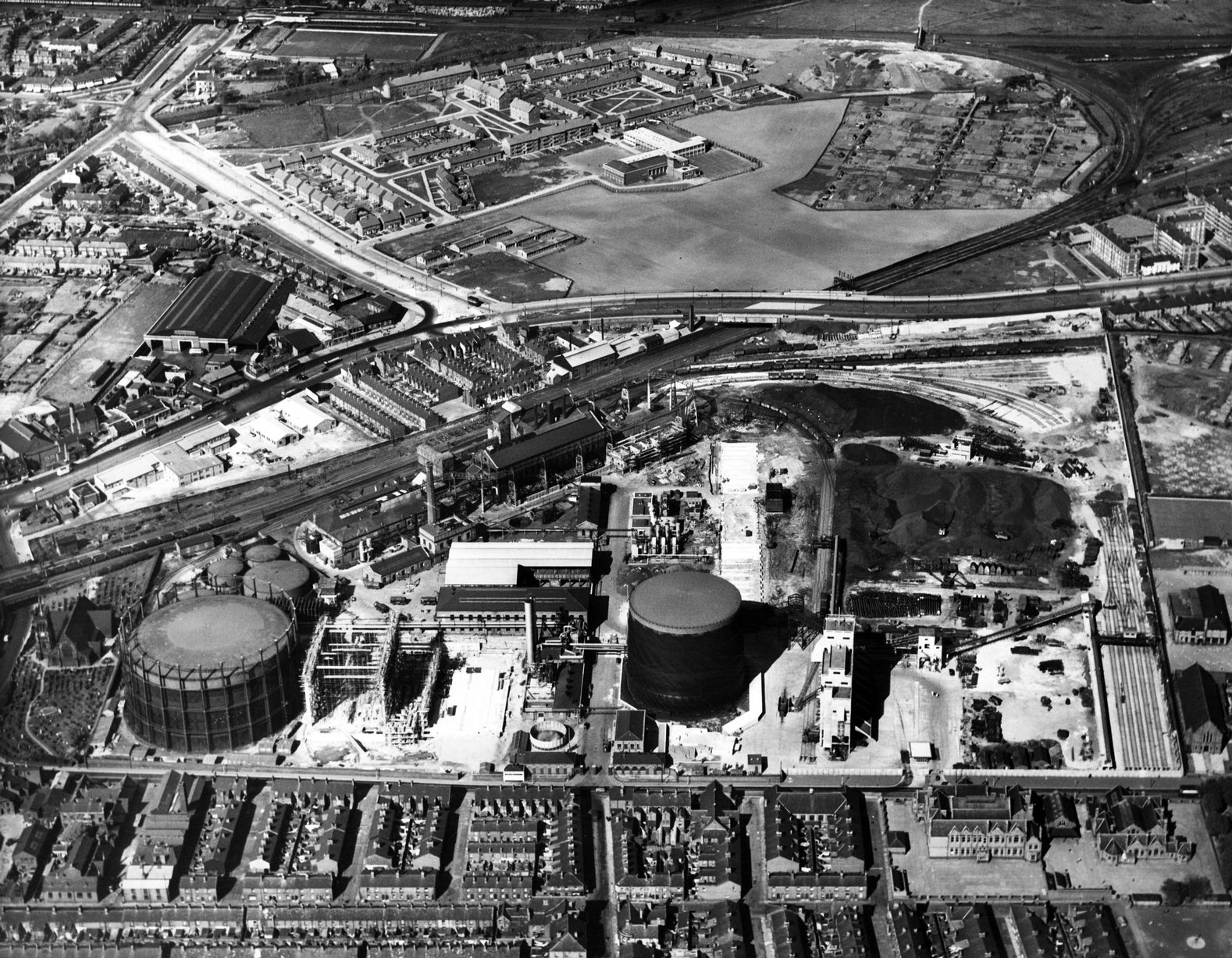

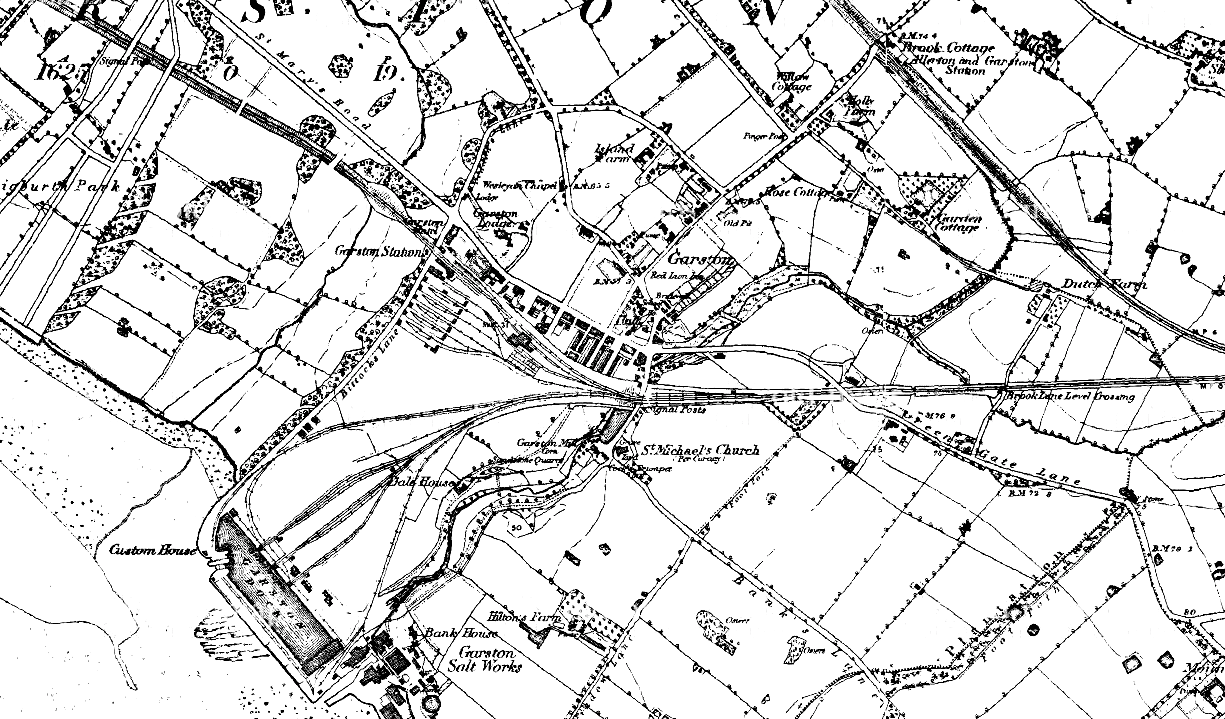

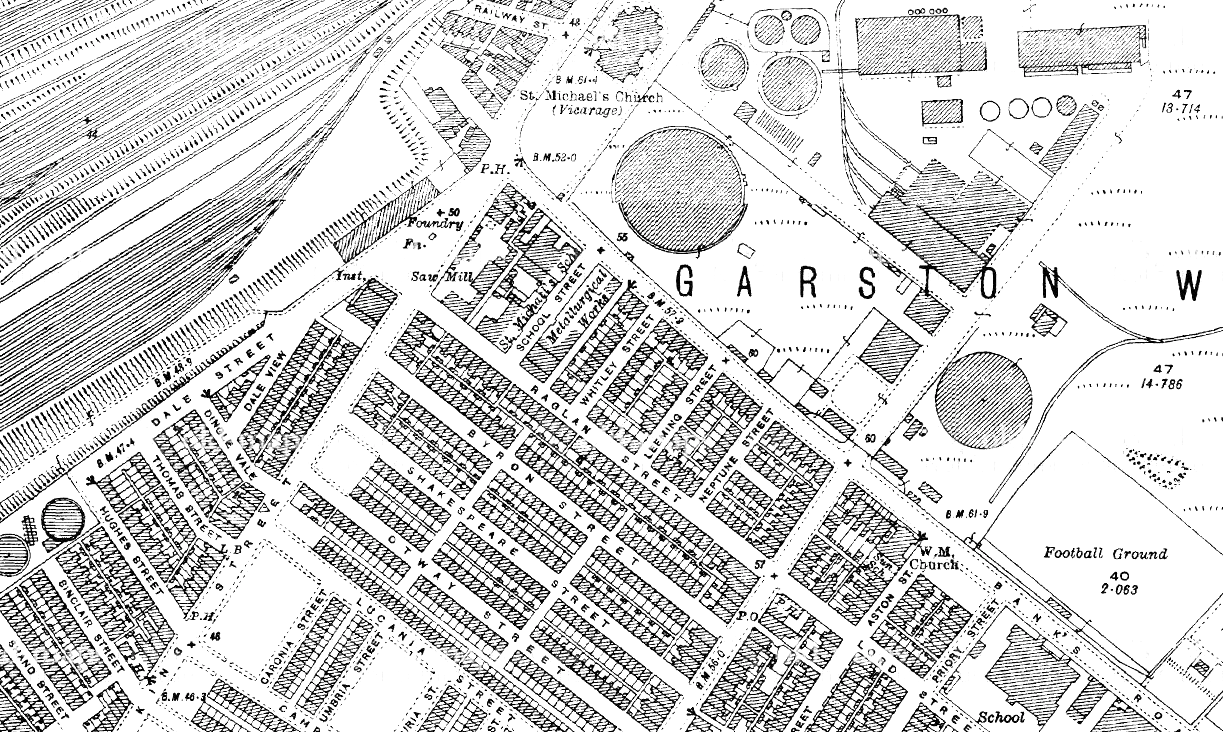

Garston c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

Landscape

Garston is a township which lies on the banks of the River Mersey, a few miles upstream from Liverpool. The history of Garston is dependent on its position on the river, with links across to Birkenhead, as well as inland. This became more important with the coming of the railways, where Garston’s closeness to Liverpool made it a good transport link between inland Lancashire via rail and the rest of the world by water.

Topographical

Mossley Hill is the topographical feature which dominates the area. Woolton Ridge is another piece of high ground, and Garston sits in the valley between the two.

Garston Brook (also known as Garston River, or the Old Garston River), rising in Mossley Hill and Allerton, flows along the valley, parallel with the present router of Mather Avenue. Between steep valley sides, it gives water for crops, cattle and industrial power. The stream, and the point it empties into the Mersey, would have been great fishing sites from the earliest days of settlement.

The village of Garston was founded in a sharp bend in the river – perhaps defence was a consideration. Today, Garston Brook is culverted and can’t be seen (though the builders of the Garston Bypass uncovered the culvert during work). The place where it meets the Mersey is now between the Old and Stalbridge Docks.

The steep sides of the valley gave opportunity to dam the waters, and use them to drive industry. Adam’s Mill, including a dam, was built on the Brook, and further downstream a second mill dam is shown on 18th and 19th century maps.

Settlement

The central part of the village formed along Church Road. The 1849 Ordnance survey map shows St Michael’s Church at the south end, and the Red Lion Inn (only recently demolished) at the north. The oldest remaining houses are the Seafield Cottages on Chapel Road, which date back to the 1730s.

From the earliest times, tenant farmers would earn their living in the same way as thousands of others: by farming strips of land owned by the wealthy families of the area like the Norrises of Speke. Common land lay outside the farmed areas, where anyone could graze their cattle and collect firewood.

The nearby Mersey attracted fishers, and a handful of houses stood down at the mouth of Garston Brook. These buildings also housed the first workers in the saltworks. The hamlet here was protected from the worst the maritime climate could throw at them by a ‘whaleback’ sandstone outcrop.

Industry in the early centuries was small scale, and Garston was dotted with brickfields. They supplied the building trade, and only later expanded into the massive companies that they became. All those brickfields have now disappeared beneath housing.

The 1850s marked the beginning of large scale house building. Before that time, the majority of houses outside the original village were the large houses of the industrial managers, such as for the saltworks.

When Liverpool expanded to engulf Garston, and the latter became a suburb, the rapid expansion created health problems. Like those in parts of north Liverpool, houses were subdivided into six or more dwellings when they were designed for no more than four. When housing was at its densest, such as in the 1907 map, outbreaks of fever were common. Population had rocketed from 2700 people in 1850 to 17,300 in 1900, and only the later reductions in density alleviated the disease risks.

Industry

Early industry: mills and dams

The very earliest ‘industry’ in Garston was similar to many other places in Lancashire and across the country. There was certainly a King’s Mill from 1066, where the king had sole rights to grind corn. This right was rented out to local lords, and then to the miller and tenant farmers in turn. Mill rights were a powerful tool for the king. Like land rights, he used them to reward, and cement his alliances with, people who had been useful to him in conquest.

Adam de Gerstan owned the mill in 1226, and sublet it to Roger the Miller. Other mills in the region were those in Dale Street, the Dingle, Ackers Mill, and mills in Wavertree and West Derby.

Garston Brook was redirected to turn mill wheels, and mill dams created mill ponds which were used when dry periods caused the stream to stop flowing. Field names from the 19th century are evidence for these features: Dam Hay and Upper Mill Field are both examples. The site was later occupied by the bus depot on Speke Road, and a later map shows the remains of a mill race nearby.

A fulling mill owned by the monks of Stanlawe could be found in medieval Garston. A fulling mill required land nearby to ‘tenter’ the cloth produced, so the mill would have had fields nearby. The Garston Historical Society has discovered a telling quote from the voucher Book of Whalley Abbey (the parent abbey of Stanlawe) in relation to industry. Adam gave:

all the water which falls from Adam’s Mill of Garston as far as the Mersey, and a plot of land for the building of a tannery or fulling mill upon the said water, whensoever they may see to be most expedient between this said mill and the Mersey, and of every kind of profit of the pool and easements of pool water ….. and also a fishery in the Township of Garston, called Lachegard, or mill pool.

Industry was clearly a crucial part of ecclesiastical life.

Adam’s Mill had an ‘overshoot wheel’, and Garston Brook was put in a culvert to power this. There were several water mills between Adam’s Mill and the Mersey, and the quote above tells of a fishery too. The Garston History Society believes the remains of Adam’s Mill lie underground across the street from St. Michael’s Church.

Below Garston Hall was a Mill Dam, with a pool fed by two springs, one which rose in the Camp Hill area and the other near Elm Hall in Allerton. The second of these crossed Rose Lane and Pitville Road, running parallel to Melbrick Road and under the bridge at the foot of Greenhill Road. Over the Dam was Garston Bridge, and below it was the Lower Pool. It then ran into a third dam, the outlet of which ran into the Mersey where Garston’s South Dock is today.

Factories

Besides the steep-sided valley inland, Garston’s south west portion stood next to the Mersey. This was a broad swathe of flat land perfect for industrial expansion.

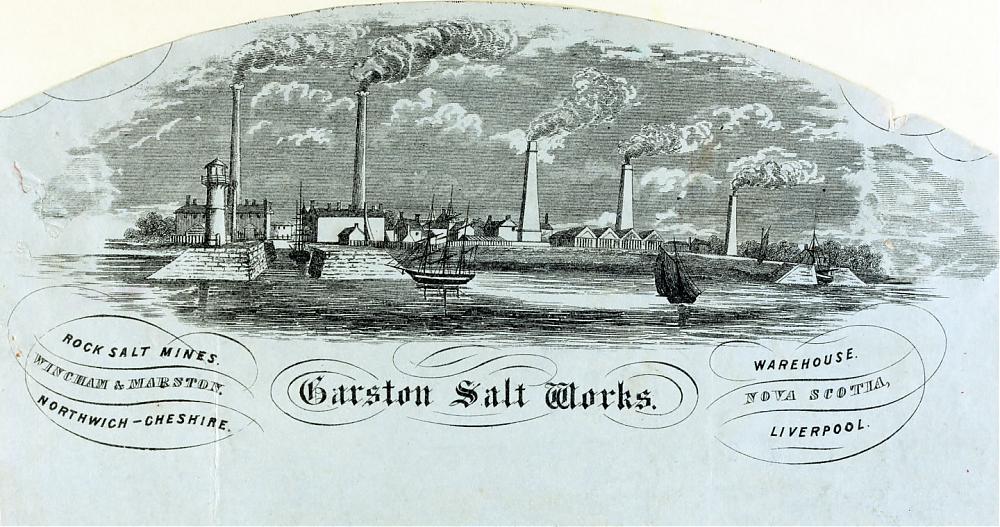

Garston Salt Works

John Blackburn owned the salt works which stood in the centre of Liverpool at the Salthouse Dock. He moved his works to Garston when the city centre location caused problems for expansion and transport connections.

He built a small dock in 1793 for the use of his new salt works. Rock salt was brought by boat from Nantwich in Cheshire via the River Weaver and the Weaver Navigation. Coal for the salt works was brought from the St Helen’s Coalfields down the Sankey Canal.

The works were sold to the London & North West Railway in 1867, and were later cleared to make way for the Stalbridge Dock.

Garston Industry

Colonel Hamilton of Windsor was one of the first people to spot Garston’s potential for development. He built a sea wall, with similarities to Jesse Hartley’s architectural style, on Garston’s river front.

The sea wall allowed Francis Morton’s company to build the Hamilton Iron Works on the site. Morton’s manufactured steel for the likes of Clarence Dock Power Station, Stanley Abattoir, Brunswick Dock Grain Silo, the No.1 Hangar at Speke Airport, parts of Everton F.C.’s football stands and the uprights for the Liverpool Overhead Railway.

From this point onwards, other industries sprang up. Garston was home to shipbuilding, graving docks, chemical works, distillers, the Garston Street and Iron Company, Bibby’s copper rolling mill, and tanning and saw mills.

Garston has an important history of match-making centre from the late 19th century onwards. R. Bell and Company Ltd built their Mersey works on Speke Road in 1887. A new factory was built when, in 1919, Bell’s was taken over by Maguire, Paterson and Palmer Ltd. Bryant and May built their famous Match Factory in 1922.

History of Garston brickworks

Brick fields had been common from very early on, and so brick ‘stools’ could be found right across Merseyside. By the end of the 19th century each brick maker had their own dedicated stools, and these developed into large manufacturing sites. Robert Tushingham had had a warehouse, machinery and other buildings on Speke Road.

Garston was perfectly placed to take advantage of the railway. Bricks could be exported north via Liverpool or east into the country’s interior. The railway itself was a major customer, for station buildings, tunnels and cuttings amongst other things.

The Garston Bobbin Works was the largest bobbin works in Britain. Garston supplied the Lancashire and Yorkshire cotton mills, and brought timber from Ireland through the docks as a raw material.

However, in the late part of the 20th century industry declined as manufacturing moved elsewhere. The button and window frame factories closed and the tannery reduced to working at half its former capacity.

History of Garston Docks

It’s often forgotten by outsiders that the docks have always been so important for the history of Garston. This point on the River Mersey was once the highest place to be reliably navigable by ships, and so the docks had the advantage of being the furthest upriver.

But the Mersey is never kind to her banks, and erosion remained a problem. The walls erected by pioneers tended to fall into the river before long, although sloping walls at Otterspool were more successful.

After the first docks appeared in Garston, it was suddenly worth widening and surfacing formerly muddy tracks in the township. Crushed rock was in ready supply when building was in progress.

A small dock built in 1793 for Blackburne’s salt works was the first of its kind in Garston. The Blackburne Brothers had built salt refineries in Hale and Liverpool (at the Salthouse Dock) by 1692. They moved their salt works from central Liverpool because the city centre location eventually made transport difficult, and there was little space for expansion.

Two tidal docks at Garston (the Salt Dock and the Rock Salt Dock) allowed boats to bring unrefined salt from Nantwich in Cheshire, with the finished product shipped out via the Mersey. Coal for fuel could be brought from the St Helen’s coalfields. By the time the factory closed in 1865 there was quite a complex in Garston, including workers’ cottages, a boiler house and a smithy.

In 1865 the St Helens and Runcorn Gap Railway Company built another dock. This would later be known as the Old Dock when the North Dock was built next to it, and was built out from the river cliff. The Stalbridge Dock opened in 1907 on the site of the old salt works

Transport became an essential part of the history of Garston, and so the population expanded alongside it. By 1937 there were 93 miles of railway sidings at Garston Docks, 8 miles of which ran along the docks’ quays. Unfortunately, as with Liverpool itself, newer ship sizes found it hard to come upriver far enough. Industry declined as a result, and although Garston is still a port – and run independent from Peel’s Liverpool port – the docks no longer play the central role they once did.

Garston Hall

Garston Hall started its life as a monastic grange – one of several owned by the Benedictine brethren of the Priory of St Thomas the Martyr of Upholland. It was already in existence in 1334, although the final Hall dated to around 1480. The Hall was H-shaped in plan, and was encircled by a moat, as well as a wall which might have been older than the Hall itself.

It appears only on the 1849/50 Ordnance Survey map, but was demolished in the 1880s. The plot is now occupied by Sidwell Road (once Back James Street) and the Garston Empire.

Stanlawe Grange and Aigburth Hall

As a building of the 13th century, Stanlawe Grange is the oldest building in Liverpool. It once consisted of a detached Hall, barns, monks’ quarters and a granary. There were also outbuildings, whose open sides faced the hall.

Stanlawe Grange was one of a number of granges – farms in the landscape – which belonged to the Cistercian Abbey of Stanlawe on the south bank of the Mersey. The site of the Abbey is now in ruins, isolated from the area of Stanlow by the Manchester Ship Canal. The monks moved to Whalley, though they kept their lands in the area until Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in 1536.

Stanlawe Grange was once part and parcel of a cluster of buildings which included Aigburth Hall. Aigburth Hall once stood across the road, on a site now occupied by 1930s semi-detached houses. Unfortunately, much of the original Hall, and some barns, is lost. The Hall was demolished before the 1840s, and as Aigburth itself became built up a barn close to Aigburth Road was demolished.

Other features

Garston Chapel

The current church in Garston is probably the third or fourth on the site. Garston Chapel was the first building, and was in existence in 126 when Thomas de Grelle gave it to his son, Peter. The Chapel was dedicated to St Wilfred, and some remains of it were found in 1888 when the 18th century chapel was demolished.

Garston Cross

The base of a cross lies near the site of the old chapel’s porch, while another was close to the mill dam, on the banks of the mill pool. The base of a cross was re-erected near St Francis’s church.

Mill Road Workhouse

Mill Road was Liverpool’s first workhouse – in 1835-45. It had 690 beds and a 150-bed mental hospital. Later it became the Mill Road Maternity Hospital.

References

Garston Industrial Development – Garston History – An Introduction to the Industrial Development of Garston. http://www.garstonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/garston_industrial_development.html (accessed 30th January 2018)

In pictures: Garston remembered in photos from the Echo archive https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/nostalgia/pictures-garston-remembered-photos-echo-7268345 (accessed 30th January 2018)

Mike Royden’s Local History Pages – Monastic Lands http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/mrlhp/articles/mikeroyden/liverpool/monastic/mondoc.htm (accessed 6th Feb 2018)

http://www.liverpoolhistorysociety.org.uk/garston-speke/