Childwall, once a suburb, remains a green space within Liverpool. There is a surprising number of streams, wells and brooks, and a green, sometimes park-like appearance kept across centuries.

Childwall remained a small hamlet right up to the beginning of the 20th Century, commanding impressive views across large areas of Lancashire and Cheshire, and the Mersey. After the two World Wars it grew as a prosperous suburb.

Book

I don’t know of a good book about Childwall history. Could you recommend one? Leave a comment below!

Website

Although a little difficult to read due to scrolling and size issues, this is a comprehensive account of Childwall’s history, with plenty of images to boot.

Childwall c.1900

Use the slider in the top left to change the transparency of the old map.

Monastic Fakery

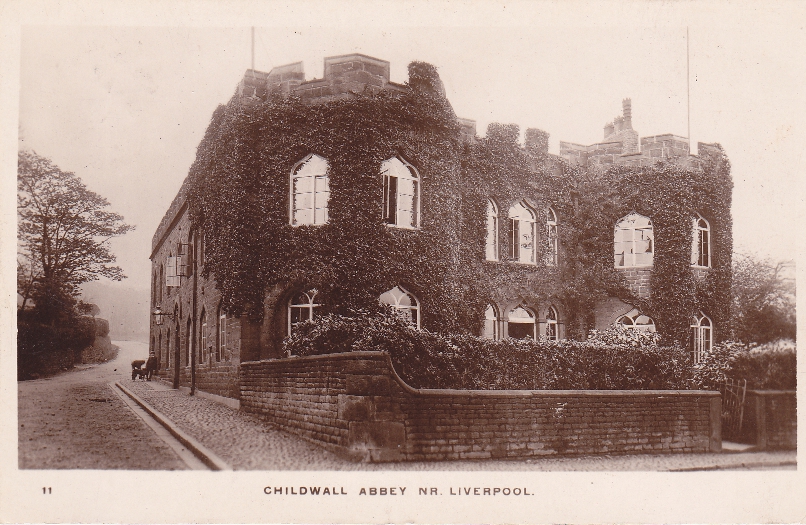

To examine Childwall on a map today is to see reference to an Abbey and a Priory. Older maps may mention ‘Monk’s Well’ or ‘Monk’s Bath’, and mark the place of a ‘Cross (remains of)’.

But there has never been a functioning Abbey or Priory, and the now-resurrected cross probably marked the boundary of the township with its neighbour of Woolton.

The Childwall Abbey hotel, with a possible date in the 15th Century, is the oldest part of the village. However, the tradition that Childwall was the location of an abbey may have begun when Childwall Hall was extended in an ecclesiastical style.

Childwall Priory, on the other hand, was the name given to a farmhouse to the north of Childwall Priory Road, which also had an extension (in the 1820s) which resembled a church. Whether this extension was following a fashion laid down by the hotel and Childwall Hall is hard to say.

Watery Township

Before it became a built-up area, much of the north bank of the Mersey consisted of mosses, peats and moors (shown in names such as Black Moor, Black Moss, later Black Horse, Lane, Gill Moss). Childwall (‘field of the well’) was a great example of this.

Even today evidence for water in the township is easy to spot. Well Lane runs to the south-east of the church. Childwall Brook still lies to the north-east of the village. Childwall Valley Road still regularly floods after heavy rains, and large puddles and damp ground can be found on Score Lane Gardens.

Other names can be found on older maps. Mire Lake and Monk’s Bath are both features which have long since disappeared beneath the city. Monk’s Well, 200 yards from Childwall Abbey Hotel, was probably the feature which gave the village its name. In 1965 workmen found a stepped well at the corner of Childwall Lane and Well Lane, which they later filled with gravel and covered.

Childwall Brook springs up near Well Lane and Score Lane, at a point marked on maps as Monk’s Bath. This flowed towards Jackson’s Pond (marked on maps as ‘Cistern Pit’) which lay between the Loop Line and Gateacre Park Drive. This area is now covered by playing fields.

The Edge of the City

Childwall remains a green and pleasant suburb. For most of its history this was even more apparent, with masses of green space. The few houses which did stand here were large and widely spaced. The two main residences were Childwall Hall and Childwall House, with only a handful of other buildings in the village. The roads from this isolated settlement were known for being sandy and unpleasant.

Childwall Station once stood off a track from Well Lane. This was once part of the Liverpool Loop Line, which was an early casualty of Dr Beeching’s closures. This early closure was just one clue to the rural nature of Childwall until very recently: there were simply not enough passengers to sustain a station, and the village was quite a distance from it from the start.

As we’ll see below, Childwall started out as an isolated village, and even though Liverpool encroached over time, as a suburb it retained a greener character right up to the twenty-first century.

Childwall Through the Centuries – Maps

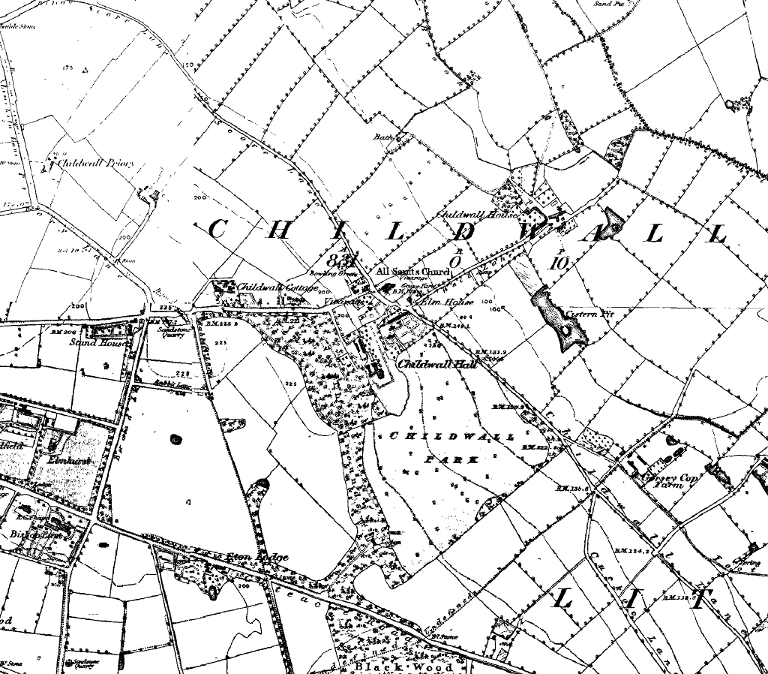

Childwall as a Village (1849-50)

The earliest available Ordnance Survey maps show Childwall to be a small village on the east side of Liverpool. There is little more than Childwall Hall, plus the church of All Saints. Named on the map are Childwall Hall, Childwall House, Childwall Cottage, the Abbey Hotel, Ivy House and the large green areas of Childwall Park and The Grounds to the south of the Hall. This is the small centre of Childwall, around the crossroads, although there are a handful of farms and large houses dotted about the nearby countryside.

The crossroads – Childwall Abbey Road, Well Lane, Score Lane and Childwall Lane – are the most ancient roads in the district. Score Lane leads to Broad Green in the north, Childwall Lane to Gateacre Village in the south. Childwall Abbey* Road merges into Dunbabin Road on the way to Liverpool in the west, while Well Lane peters out on its way to Childwall House.

Looking slightly further afield reveals Childwall’s lack of importance at the time: the Manchester-Liverpool railway already services Broad Green (now the oldest in-use station in the world), but no such service comes to Childwall.

Larger houses

The large houses which were to become the basis of later institutions are scattered around. Stand House is at the junction of Dunbabin Road and Taggart Avenue (known at this early point as Broad Lane). This house has a walled garden on Dunbabin Road, as well as five fields behind it, now taken up by the dense roads between Dunbabin Road and Irene Road. The other half of this block is taken up by Standfield and Elmhurst, the latter now part of Hope University. Over the road was Bishop Eton and Eton Cottage, separated by Green Lane. Woolton Lodge marked the south edge of the township, and its boundary with Woolton. Roby Hall lies in the north east, near the railway.

Water features

As mentioned above, water features present on this map show where perhaps house-building was not possible. ‘Cistern Pit’ (Jackson’s Pond) is now covered by the Alderman John Village Garden, while the present site of Score Lane Gardens was then occupied by Monk’s Bath. In addition to this there are pools dotting the area: a large pond to the north of the cistern, several around Gorsey Cop and Cockshead Farms, another where Hope University now stands on the east side of Hope Park, as well as a whole group of them on the area marked ‘Carr’ to the north east. This area is covered in long, narrow fields, suggesting the unsuitability of this land for the enclosure-type square fields covering the rest of the township. Finally, Childwall Brook runs south-east – north-west near Childwall House, all the way from Monk’s Bath to Broad Green.

Another characteristic feature of late 19th Century Childwall are the sand pits. The area to the south of what is now Childwall Triangle is marked as a sand quarry (and the northern side of the triangle is only a foot path). There are other sand pits: near Court Hey and south of Bishop Eton house.

The Railway Arrives (1894)

The most striking feature of this late 19th Century map is the Cheshire Lines railway which finally brought the trains to Childwall in 1879. Now part of the Liverpool Loop Line footpath, the track ran north-west to south-east, passing under the Manchester-Liverpool line at Broad Green. The station itself stood slightly away from the village itself, off Well Lane, the traces of which are only visible in the widening of the cycle track, and a path off the south-west side of the path.

Right from the start a ramp allowed foot traffic to pass over the railway. On the 1894 map the ramp joins two fields, but now joins Bentham Drive with Chelwood Avenue via Lanfranc Way and Lanfranc Close.

The number of houses is beginning to grow by this point, although the number is still low. The majority of new houses stand to the south-west, in the direction of the ever-expanding Liverpool.

Broad Lane is labelled ‘Park Road’. The area to the east of it is now Stand Park.

Liverpool Polo Ground sits on land now occupied by the roads between Hattons Lane and Taggart Avenue.

Dudlow Lane, which was marked and named on the 1849-50 map, has the Liverpool Water Works on it. This indicates increasing density of population, and the forward-thinking of the local government. The building marked as Dudlow Hall in 1849 is now Dudlow Grange.

Little Change (1908)

Although little may have changed on the ground, more detail is shown. The boundary of the Liverpool Polo Ground is now shown. The area has also joined several fields together, all contained within it.

Other than this, very little changed in Childwall between 1894 and 1908. While this is not a very long period, it goes some way to showing the continuing rural nature of the township.

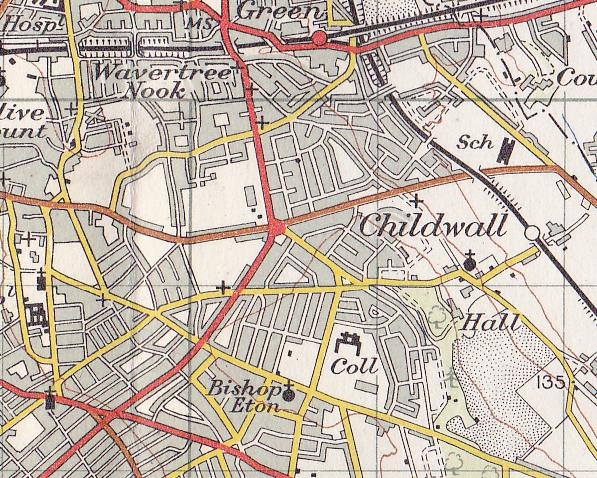

Childwall Joins the Suburbs (1928)

It’s at this point in Childwall’s history that suburbanisation really starts to show.

Beech Lane is now Menlove Avenue. Priory Road splits in two, with the northern part becoming part of the new Queen’s Drive. The southern end is now Childwall Priory Road. Both the Queen’s Drive section of Priory Road, and Menlove Avenue have been made into dual carriageways. A very forward-thinking development considering car ownership had only begun to take off in the previous 20 years.

The Liverpool Polo Ground had already by now been broken up to use the land for housing. Green Lane North, Irene Road and Oulton Road already had houses on them, while Terence Road had just been laid out.

Allotments for new residents were laid out in two areas around the junction of Hattons Lane and Dunbabin Road. One area of this is now under King David High School (although allotments survive to the south).

What could be described as ‘classic’ 1920s suburban road layouts can be seen north of Thingwall Road. Here, Wavertree Garden Suburb is just starting to emerge around Wavertree Nook Road.

Predicting the Rise of the Car (1947)

This edition of the OS map only adds recent changes to a base map made in 1919.

However, a big change is reflected in the local road layout. The junction of Queen’s Drive and Childwall Priory Road is now a junction of five roads. The Childwall Fiveways is well on its journey to being one of the busiest junctions in Liverpool.

The roads either side of Park Road and to the west of The Grounds are now fully covered with housing. The third side of Childwall Triangle has also been built on. A golf course was built on part of Childwall Park. Childwall Golf Club moved to this course in 1938.

Other areas nearby had also been built on by this time. The Hillside Farm area had been laid out, although only half of this was built by the 1947. The roads around Court Hey were also being laid out, and the map captures the process mid-way.

Housing was gradually filling in the gaps south of Broad Green and north of Childwall Valley Road. Childwall was now on the edge of Liverpool, but the station on Well Lane had already closed. The last passengers alighted in 1931, the last goods in 1943. The isolation of Childwall, plus the distance between the station and the village, had meant that a stop here was just not economical.

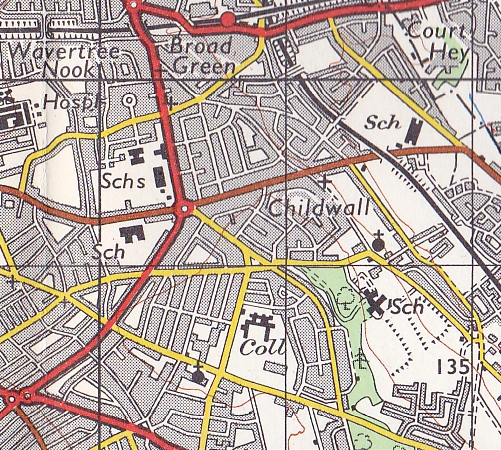

Suburban Infilling (1958 – 60)

By this time much of the road layout visible today was in place. The roads around the college were completely built up, and the area around Black Woods was full with suburban housing.

Childwall Hall is marked on this map as a school. The Hall itself was demolished in 1949, and a new college building put up in its place by Liverpool Corporation. Another school can be seen where the houses around Chelwood Avenue now stand.

New roads are still being laid out, by now to the north east of the Cheshire Lines railway, demonstrating the continued demand for homes as Liverpool expands in the immediate post-war era. Barnham Drive did not yet extend all the way to Well Lane, and there is the expansion of buildings around Orange Lane and Gateacre Brow.

The end of the Railway (1964 – 72)

As we look at progressively more modern maps, the main changes are the final gaps being filled by the suburbs.

The collection of roads around Rockbourne Avenue appear for the first time on this map, and further infilling can be seen around Orange Lane up to Well Lane.

The Cheshire Lines railway had by now been removed on the bend between Gateacre and Halewood. There was still a station at Gateacre Village, and the line still looped west towards the docks as it reached Halewood.

Motorways and New Towns (1978)

The great icon of the modern age – the M62 motorway – was now draped across the north of the township.

Another symbol of the modern city had sprung up from nothing. Netherley sprang up in the green belt in 1968, built to accommodate people moved out of unsuitable city centre housing.

Gateacre Village station does not appear on this map. The line with dashes across it indicates that it is solely a freight line. The Cheshire Line’s rails were finally lifted in 1979.

Further Reading

Friends of Childwall Woods and Fields, The History of Childwall Woods and Fields, https://www.fcwf.org.uk/history-of-childwall-woods/ accessed 11th December 2020.