The Pool is arguably one of the major reasons for Liverpool’s existence. King John was looking for a suitable place from which to launch ships to Ireland, and Liverpool fit the bill.

The Pool sprang up inland, and flowed down Whitechapel and Paradise Street into the River Mersey. Although completely invisible today, it played a major part in the whole of Liverpool’s history. From the castle built in the 13th Century, via the completion of the first commercial wet dock, right up to the modern Liverpool One development on Paradise Street.

How The Pool made Liverpool

The Romans left little trace of their presence in the area. The Norman Domesday Book mentions only the surrounding manors like West Derby and Toxteth. Place names suggest that there were Norse and Saxon settlements in the area in the period between. However, the fact remains that there was next to nothing on the future site of Liverpool before King John decided to lay out a new town and grant privileges to enterprising settlers.

We therefore have to ask why John went to such lengths. Chester was already well established as a port, and other locations on the north west coast could have provided him with a suitable launch.

A sheltered harbour

There are two reasons why the Pool was so attractive. Firstly, it provided a sheltered harbour on the edge of a river with access to the open sea. Ships were protected from the worst gales, and were much less exposed to the eyes and weapons of enemies sailing the Irish Sea.

A Defensible Promontory

The Pool carved out a shallow valley through the marsh into the Mersey. It left the harder sandstone cliffs to the north untouched and rising defensibly above it.

Liverpool Castle was not built until some time after 1207, but the ridge would hardly have escaped the attentions of John’s surveyors. Such a hill would be incredibly useful against those enemies coming down the river.

The Pool in Liverpool’s early years

Once Liverpool had become a small town of seven streets, the Pool became the defining feature of its southern boundary. The castle, built in the 1230s, watched over the ships in the sheltered harbour. This site is now occupied by the Victoria Monument in Lord Street, while Pool Lane ran from the castle down to the water’s edge.

A bridge crossed the Pool at the end of Dale Street (near the present Queensway Tunnel entrance). Just beyond this was the Fall Well, an important water source for the growing town.

Lord Caryl Molyneux built another bridge across the Pool at the present junction of Lord Street and Church Street. Molyneux had asked permission to lay out Church Street and build a bridge to it over the Pool, but went ahead with the construction before being granted it.

The Council deemed the bridge’s construction illegal, pulling it down again soon after. This was just one of many examples of rivalry between the merchants (the Council) and royalty.

The Pool remained a source of controversy for decades as locals often dumped waste into it. The town fined people for this crime, as this water fed the wells which gave Liverpool its drinking water.

Filling in The Pool

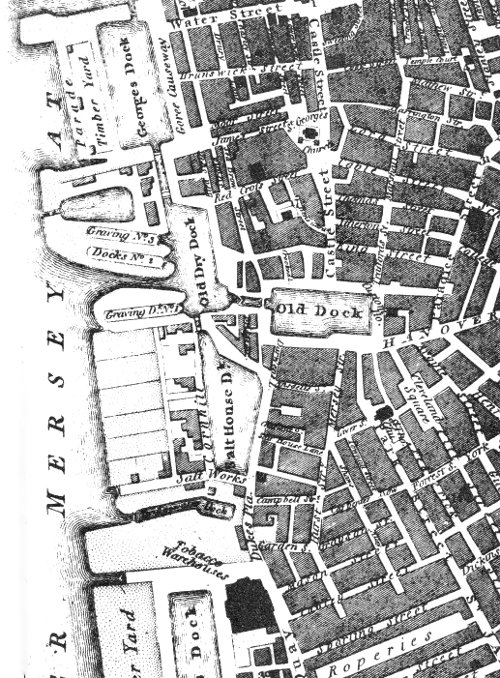

The end of the Pool came in 1709 when work began on Thomas Steers’ pioneering dock (the ‘Old Dock’). The dock opened in 1715, and was the first commercial wet dock, protecting ships from the River Mersey’s huge tidal ranges. Thus the Pool was the very birthplace of Liverpool’s later commercial successes.

Today, the Old Dock is preserved beneath the Liverpool One development. To study a map of the city centre is to trace the course of the old waterway up Paradise Street, up Whitechapel and Byrom Street, where it began.

Mark kinnish

says:Hi

My question is any part of the medevil bridges still there under ground.

Hope to hear from you soon

Regards Mark Kinnish.

Martin

says:Hi Mark,

I know that part of the Bridge between Lord Street and Church Street was found when sewers were dug in the 19th century, and the historian James Picton says that the bridge was left in place, and buried in 1873. I don’t think anyone knows for certain whether that is still there, but perhaps we’ll get to have a look one day! I’m not sure about the bridges which might have been further up the Pool.

Martin

Rob

says:Hi Martin,

In 1635 a quay was built in the Pool – do we know what sort of quay?

Cargo of the period would have been ferried from ship to shore using smaller craft and the advent of a quay from which merchant ships could tie up would had been a major advantage.

Picture and period maps of the time show the pool having a tidal edge with ships at anchor or beached with no evidence that the quay was suitable for landing deep sea merchant vessels.

Do you have any knowledge on this?

1715 Dockable hard quay

Rob

Martin

says:Hi Rob,

I think the assumption (as there’s no primary source evidence I don’t think) that there were jetties out into the pool for boats to moor alongside. I think for many years the main boats coming into the Pool would have been used to tying cargo down so that it wouldn’t slide around when the tide went out. They were small enough to make that something that could be put up with. Then when the ships got bigger smaller boats would get the cargo offloaded before low tide. I think bigger ships get into trouble if they let themselves sit on the sloping sands.

I think the 1635 quay was a stone affair, and came about while thoughts were already turning to enclosed docks. Enclosed docks were so expensive that it would take a lot of ambition and risk to pull off. I think the stone quay was a safer bet, but one that proved too small for Liverpool’s ambitions. It might be that this was still only suitable for the boats which ran from ship to shore.

Best wishes,

Martin