In the woods above Woolton lie mysterious remains, amounting to little more than some dry stone walls, in a location reputed to have once held so much more.

Camp Hill is a name which suggests a settlement, if only temporary, with perhaps a military usage, and for years it has been assumed that the site was once the location of an Iron Age Hillfort. Hillforts have been defined as defended upland fortifications where high-ranking chieftains would gather their people around them and plot against their enemies, trade with allies, and swap war stories around the campfire, amidst much mead quaffing.

More recent research has cast doubt on these ideas, however. For a start, the archaeological evidence from the hillforts dotted around the country is extremely varied. Some forts had three or four huge ramparts, and were certainly heavily defended. There was even evidence (in the form of human bones with arrows embedded in them) of periods of violence at these sites. At the other end of the scale were smaller sites, with less evidence for defensible banks, and sometimes had very little evidence for any kind of activity in them at all. Shapes vary too. Even the period can’t be pinned down – some sites date from the late Bronze Age, though the majority can be placed in the Iron Age.

The upshot of this is that the vague phrase ‘hilltop enclosure’ is closer to the mark if you want to encompass all the sites that are known.

What are hilltop enclosures?

If these enclosures aren’t defended hillforts, then what were they for? Archaeologists have come up with some sophisticated and subtle theories which match the evidence which has come out of the ground.

Cattle corralling is one definite use, and some hilltop enclosures were used for human habitation as well. Religious and ceremonial activities were probably carried out too, at least at some of these hilltop sites.

And even if they weren’t defended, many of them would have been important symbols of power.

The landscape of Camp Hill

Like many similar sites, Camp Hill rises above the local area on a prominent stretch of high ground. Although there were other hills in the area, like Mossley Hill and other Merseyside uplands, for the locals of future Woolton, Camp Hill would have been of special importance, if only for its sheer presence.

Even if it was not inhabited, or defended, the hill would have acted as a recognisable landmark, a sign to returning travellers that they were home, and a reminder to visitors that a community who could build great monuments lived here. The number of hours work which needed to be put in to build such a monument was proof of the community’s ability to pull together for a common cause.

Further afield, links with neighbouring tribes may have been reinforced by the enclosure. It’s been shown that similar sites in Cheshire and Staffordshire, such as the well-known one at Beeston Castle (which has prehistoric origins), which were in use at the same time as Camp Hill, would often have been visible from each other. Vegetation or adverse weather conditions might have reduced this visibility, but it would have been easy to light a beacon, and at the very least remind your neighbours that you still existed in the gloom!

So whether or not the ‘camp’ was occupied for any stretch of time, it was an important monument and landmark in the most basic sense. You could compare it to Liverpool’s own St George’s Hall: it’s not only important when it is in use, but its very existence strengthens the community bonds of those who would pass it daily.

The evidence

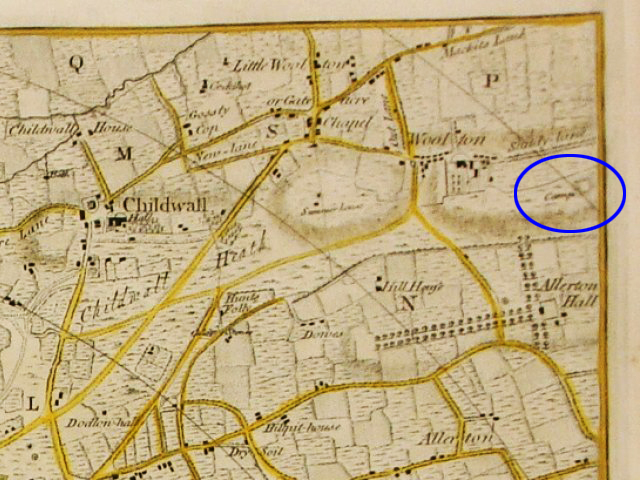

It’s been suggested that Camp Hill was built in around 150BC, during the Iron Age. The first modern evidence is in map form, as a ‘Camp’ is marked on the Yates and Perry map of 1768. It’s a rough, almost square enclosure on this map, and may not reflect any remains visible on the ground.

Excavations took place on the site in 1952 when a trial trench was dug in the area. Some small drystone walls were uncovered, but nothing was discovered which could date the remains with any certainty. The site is thought to be located near the Sunken Garden in Woolton Woods.

With this lack of firm evidence it’s possible that Camp Hill is nothing more than a legend based on local folklore. The site is on the edge of the large group of hilltop enclosures scattered across Cheshire and Staffordshire, so little research has been done on it.

Despite this, it’s worth keeping in mind that prehistoric Merseyside was more densely populated than is usually thought, and Camp Hill, if it existed, would have been part of a landscape which was incredibly important for locals while also sending out signals to fellow communities dozens of miles away.

Today: Woolton Woods

Today Camp Hill falls within Woolton Woods, a part of the Woolton Hall estate which was owned by the Ashton family from 1772. It passed through the Shand and Gaskell families until it was bought by the City of Liverpool in the 1920s, and is now a public park.

Since that time it has been laid out as gardens, more formal in feel than the other parks across the city. It’s possibly best known for the floral clock, and the tranquil and sheltered places it harbours.

References

Woolton Woods and Camphill – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woolton_Woods_and_Camphill (accessed 12th December 2015)

South Liverpool, Woolton http://www.allertonoak.com/merseySights/SouthLiverpoolWO.html (accessed 12th December 2015)

Saunders, T. (ed), 2014, Hillforts in the North West and Beyond, Archaeological North West: New Series Volume 3 (2014), Council for British Archaeology North West

Image: Camp Hill, Woolton, by Sue Adair, via Geograph, released under a Creative Commons Attribution License